A Shortcut for Caring for Others (and Being Cared For Yourself)

This isn't a hack, it's just straightforward

Many of the people who read this newsletter the most are those who haven’t yet converted to a paid subscription. If that’s you, and you have the means, consider paying for the things that have become important to you. (If you don’t have the means, as always, you can just email me and I’ll comp you, no questions asked). Subscriptions make work like this possible.

(I’ll also say that this week’s Things I Read/Consumed and Loved is, again, very, very good — if you subscribe and back-access, just email me and I’ll send it your way, and you’ll also have access to all future Things I Read and Loved).

We talk a lot in this newsletter — and as a subscriber community — about forming communities of care. We’ve talked about how to show up for your friends without kids — and how to show up for kids and their parents. We’ve talked about the importance of inter-generational communities, and the general exhale of relief that comes when you realize you don’t have to sell your life today, and what happens when a lack of other options results in coerced care.

Do I wish that the U.S. government took the formation of a social safety net seriously, and eased the pressure on these communities of care? Absolutely. Do I want to work towards making every day more sustainable for everyone in the meantime? Yes. Which is another way of saying that this is absolutely a structural problem, and while we figure out how to make structural fixes permanent, we need to figure out how to give and receive care on the ground. I want to underline the two parts of that last sentence: a lot of us are good at giving or being ready to give care. But we also need to be better at asking and receiving it, because all of this community work depends on divorcing ourselves from an understanding of anyone, anyone, as uniquely givers or receivers.

But the reality is: a lot of us are very, very bad at giving or even asking for, let alone receiving, help. This Friday’s Subscriber thread goes deep into the reasons why — and here are some of its recurring, challenging themes:

1.) Independence and self-sufficiency have been or have become a core part of your identity — either out of necessity (as a trauma response) or because their independence and self-sufficiency was praised and valued (see especially: white rugged individualism). To ask for help feels like undercutting your entire self.

2.) You haven’t been around examples of healthy community or dependence — particularly within your family — and don’t have models of what it means to safely ask for help. This is particularly true for people whose independence is, in some way, a trauma response, but I also think it’s true of people who grew up in homes where the adults were solitary or isolated, or where everyone in the family talked shit about other members of the family who asked for help.

3.) You’ve always been the helper, whether in your vocation/job or just within your friend group. Again: to ask for help would be to undercut that identity. See especially (but not exclusively) Moms, care workers, teachers, etc.

4.) The feeling that because of how your life outwards appears — “together,” “without children,” “without physical signs of illness” — that you shouldn’t need help, because you have it so much easier than your friends/family who have ostensibly more “difficult” lives. Everyone’s lives are difficult in different ways but we definitely rank difficulty and equate “easier” with “never ever needs help.”

5.) Previous attempts at reaching out for help have been rebuffed or ignored, and it hurt so much that you never want to ask again. This one’s really hard. It’s also related to the feeling, as one commenter put it, “that there’s no help to be had.” Everyone else is just treading water.

6.) You feel that you have so many ongoing needs that you need to preserve your “asks” for when you really, really need it. This is particularly true of people who are disabled or are dealing with chronic illness — you feel like you don’t want to go back to the well too many times.

7.) Through upbringing, culture, or family, you’ve internalized that suffering is good, and asking for help is asking to alleviate that important suffering. See: a lot of Christian religious traditions. If/when you try to avoid that suffering, there’s a sense of shame in asking for some measure of ease.

8.) Masculinity, masculinity, masculinity. Real men don’t ask for help, etc. etc. I don’t have to elaborate on this one because it’s so simple and so frustrating in its simplicity and endurance.

9.) Simply not having the community or family or friend group that you feel comfortable enough to even ask for help in the first place. This is particularly hard for people who’ve moved to a new place, people without family they trust, people who’ve been alienated from their former friend group because of pandemic practices or politics, people who’ve left their religious tradition, etc.

10.) You feel so overwhelmed that you don’t even know what to ask for. People might ask you if there’s anything they can do to help, but you have no idea where you’d even start. See also: not even realizing that you need it, in part because we’ve been conditioned to ignore our body and mind’s calls for help. As one commenter put it, “I’m just ploughing along through weeks and weeks as life is getting incrementally more overwhelming and difficult and I just keep thinking why does everything feel so bad until one day I can’t get out of bed.”

Some of these struggles are deeply psychologically embedded — and no matter how much structures change, no matter how much you seek out community, you’re still going to be battling the fundamental belief that you’re a burden. How do you unlearn that? Therapy is a really good place to start. I appreciated this comment from Friday’s thread:

I have been working on this with a therapist all year. For me, it's been my core identity and understanding of myself that I am completely independent and I DO NOT NEED HELP. That identity was definitely fostered by recognition (when I was a kid) from adults for independence, competence, etc.

On top of that, I am very intuitive when it comes to other people needing something (hello trauma response!) and just assume that if nobody is actively offering something up to me, they don't want to help.

So, it turns out that a) people cannot read my mind b) people actually love helping when they can and c) my worth as a human is intrinsic and I'm not weak/failing/incompetent if I need help. Still working on all of that, but it has been a revelation to start asking for what I need at least some of the time, and to recognize that being hyper-independent actually isn't all that great and start building a community of care.

I also think it’s important to acknowledge that the way we’ve arranged society has made it really difficult for others to give the sort of help we often need. Some of that has to do with how we’ve arranged cities and housing, some of it has to do with the way certain industries demand moving away from friends and family, and a whole lot of it has to do with the culture of work — and, particularly amongst bourgeois white Americans, the engrained idea that caregiving (of children, of elders, or people who need care for whatever reason) should take place within the immediate family.

So what can we do — apart from (and alongside) therapy? How can we acknowledge those ways that contemporary society has made it difficult to ask and receive help — aka to live in community — while also trying to build it anyway?

This has been the driving question of this newsletter for some time now (is it the topic of my next book???) and as important as it feels to talk about all of this on a theoretical/philosophical level, I also think there’s real value in digging around in the actual ways to start doing this work.

Enter: The Emergency/Tough Times Guide.

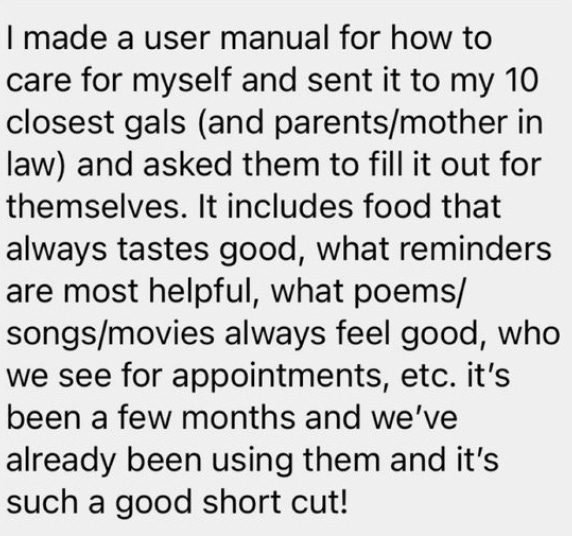

Earlier this week, I used my Instagram Stories to ask for specific examples of exactly what we’re talking about here: ways they asked or offered help within their close or loose community. You can look at some of the responses here, but the one that incited the most responses from others involved a response from a reader named Brenna, who told me about her “Guide to Me”/ “Emergency Guide”

Other readers then told me about their personal guides and shared their forms (thanks Bridget!) and Asking for a Frond (god I love online names) adapted and expanded some of the questions, turned them into a Google Form, sent them to her friend group, and then put the answers together in little “mini-guides” (sort of like a business card???) that anyone in the friend group (or the individual friend’s greater community) can consult when and if needs arise.

With Bridget and Asking for a Frond’s permission, I’ve adapted their adaptations into a Google Form that any of you can also adapt — or, if a Google Form isn’t your thing, you can look at the questions and copy/adapt them into a format that’s most intuitive for you/your community. You can LOOK at the form here (it won’t be collecting responses, or at least no one will ever actually see them!) and then HERE is where you click if you’d like to make a “copy” that you can alter and/or distribute to your own friends.

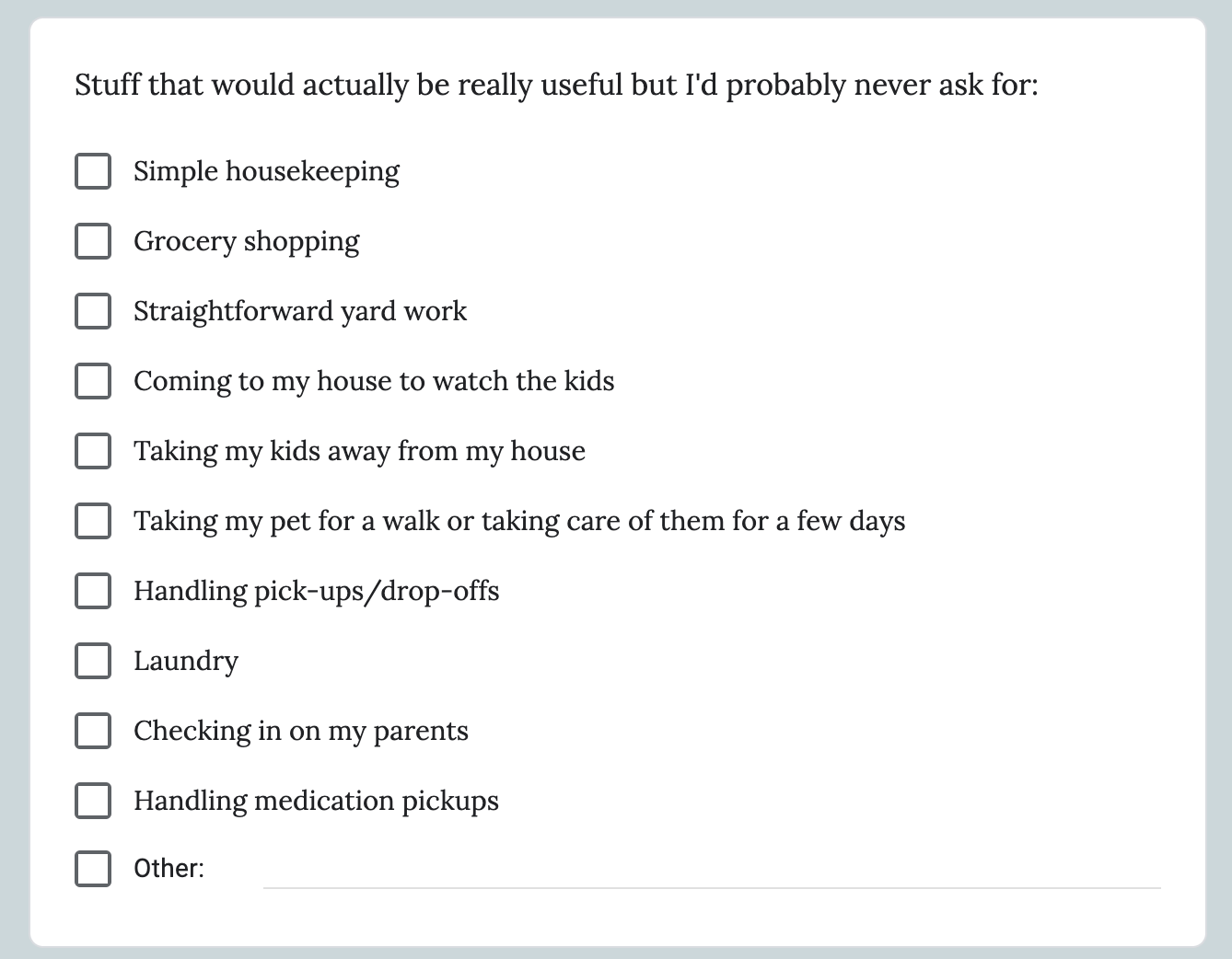

A form might seem clinical, but I find that the remove allows people to answer honestly in a way they might not if, say, you were asking them these questions in person. It also helps us move away from the dead-end of “let me know if there’s anything I can do,” which, for various cultural and inter-personal reasons, most often results in no one asking or doing anything. Instead, you have prompts like this:

The form is specific in terms of filling out small ways to help (like, what is your favorite food when you’re truly feeling low) but also in identifying the mental stopping blocks (figuring out food logistics for a memorial, communicating with extended family members) or the mundane things that would make life easier (weeding, folding laundry) right now, before the cloud of crisis hits.

Now, how should/can you use this? Lots of options!

1.) If you have a common friend mass/group, consider doing what Asking for a Frond did and spearheading a group share, which then becomes a repository for information for the entire group. Yes, this is work! But it will be so useful for your entire friend group moving forward. (I’m going to do this with my friend group even if it requires me being annoying and hounding people to fill it out). If you spearhead this, make sure that you grant end access to all of the answers to the entire group, so that when you’re struggling, others will have access to it. If you have kids, please make sure you include your friends who don’t have kids (and vice-versa).

2.) If your friendships are more point-to-point (as in, you have friends, but they’re not all friends with each other) use it as an exchange. You can send the form to each friend, and they can fill it out (and you’ll have all their info!) and then you can share your own info with them, once they fill it out. Could this be slightly awkward? Maybe! But it’s worth it. Sometimes community-building is awkward as hell.

3.) In addition to the above — consider sending it to your family. Siblings, parents, in-laws, grandparents, and beyond. You think you know what your family members need and want in times of emergency or struggle, but a lot of that is either old knowledge or (classic) what you would want during a time of emergency or struggle. So much anger and sadness within family and friend groups is the result of assuming people know things they don’t know — and doing an exchange like this is a great way to be explicit and clear with one another.

4.) See above, only, with your partner. Some of the things might not apply, but some, like the sort of things that truly make you feel better, or the labor that could make your life feel easier? There’s no harm in being explicit.

5.) Consider (with consent) working on it with a person who has consistent care needs — and distributing it to their network. It can be exhausting and demoralizing to always have to be asking for care. Having someone else help you with this, and making your needs explicit — that itself is a real act of care for another person.

6.) If your community is online/digital and the in-person parts of the questionnaire aren’t really feasible — adapt it to what you can do for one another. We’re going to be doing this in the Culture Study Discord in the weeks to come, and it’s going to make it even easier to care for one another.

Is this form going to create an instant and miraculous community of care? Of course not. But it is going to make the work of creating it just a little bit easier.

The last thing I’ll say is that if you feel like you are too underwater to even consider dealing with this sort of project, if you feel like you’d never ever be able to help anyone else with their needs because yours are too overwhelming — part of the reason you feel that way is because you need that community of care for yourself. You’re stuck, you’re drowning, but you don’t know any other way.

I know this is hard — but I think the other way is to start caring for others. It’s wrong to think of community as tit-for-tat, I-give-so-I-get, but offering care invites engagement….and accepting care models vulnerability. We cannot assume that others don’t have space to care for us, just as we cannot convince ourselves that we do not have space for others. You are not a burden; you are beloved. And if you think that you can’t offer care because you have physical or financial limitations, you’re missing the diversity of ways that we can demonstrate care for one another.

This Google Form, whatever form it takes in your life, makes it easier for us to understand what care would look like for others: it allows us to learn that language and speak it, with relative ease, when needed. But it also allows others to learn ours — even if this is the first time that we’ve even dared speak it aloud.

In the weeks to come, I’d love to hear about your experiences and experiments with this form — and hopefully we can publish a whole cornucopia of them. Play around with it, and send me an email at annehelenpetersen @ gmail.com with your thoughts.

Do you want access to the weekly link roundup and “Just Trust Me?” Do you want to be part of a community figuring out how to care for one another, even from afar? Or maybe you just want to feel like you’re supporting content that’s valuable to you. Here’s how you do it:

Subscribing is how you’ll access the heart of Culture Study. For example: on November 20th, the Job-Hunting thread of the Discord is hosting a new fangled CAREER DAY at 3 pm ET/noon PT — meant for people who are thinking about new jobs but are still kind of thinking “I have no idea just how many TYPES OF JOBS are out there.” (This is the 2nd Career Day; the first was SO GOOD).

Plus, there’s those weirdly fun/interesting/generative weekly discussion threads, and the rest of the Culture Study Discord, where there’s dedicated space for the discussion of this piece and the latest episode of the podcast, plus really useful threads for Job-Hunting, Houseplants, No Kids Club, Chaos Parenting, Fat Space, Productivity-Culture, and so many others dedicated to specific interests, fixations, obsessions, and identities.

If you’ve never been part of a Discord: I promise it’s much easier and less intimidating than you imagine.

As always, if you are a contingent worker or un- or under-employed, just email and I’ll give you a free subscription, no questions asked. If you’d like to underwrite one of those subscriptions, you can donate one here.

If you’re reading this in your inbox, you can find a shareable version online here. You can follow me on Twitter here, and Instagram here — and you can always reach me at annehelenpetersen@gmail.com.

"5.) Previous attempts at reaching out for help have been rebuffed or ignored, and it hurt so much that you never want to ask again. This one’s really hard. It’s also related to the feeling, as one commenter put it, 'that there’s no help to be had.'"

The "hurt" part is real, but it's also that when this has happened enough times, asking for help just becomes one more thing on the to-do list.

I think a form like this could be incredibly important for caregivers. I was responsible for my mother and then my aunt’s care before they died. While I tried a few times to appeal to family and friends for help, I felt like I wasn’t asking in a way that people responded. If I could have circulated a straightforward list, at least they would have known what I needed and what would have brought some joy to my elders.