Beauty Culture is Hustle Culture

Elise Hu on K-Beauty and aesthetic self-optimization

Do you find yourself opening this newsletter a lot? Forwarding it to friends? Looking forward to it? Consider becoming a subscribing member. Your support makes this work possible and sustainable.

Plus, you’d get access to this week’s really great threads — like last Friday’s massive ADVICE TIME, which featured some truly excellent takes on what to do when you’ve found yourself in charge of the eldercare of someone you hardy knew, how you know when you’re in love, how to “start” with make-up when it feels like you missed that class where everyone else somehow learned it, and how to deal with the heartbreak of teen indifference. Truly, there’s so much wisdom in this cascading thread.

I grew up in the era when you basically had three choices about how to care for your skin: you were either a Noxema person, or a Clarisol person, or maybe an Oxy person. That’s all that was really marketed to teens in the United States at the time — that, and the advice not to eat pizza, because “grease” was responsible for zits. The ads on MTV and in Seventeen told us the same thing: your skin is a problem, and these problems will fix it. When they didn’t, it’s probably because we had chosen the wrong product.

After years of “problem” skin and countless trips to the dermatologist, I finally arrived at a “skincare routine” (because the fixes have steps these days) that culminates with a generous portion of oil slathered all over my face. My teen self would be astonished, but also thrilled, thrilled, by the lack of zits.

But here’s the thing: as soon as you stop worrying (as much) about zits you have to start worrying about lines, and wrinkles, and under-eye circles, and sun spots, and freckles. You can’t fix the problem of your skin, you can only focus on new ones. And this is all intentional, of course — if you didn’t think some part of your body was broken and fixable only through consumption, then how would companies sell you things? How would our economy work? How would advertisers introduce us to vulnerabilities we didn’t even know existed and then exploit them?

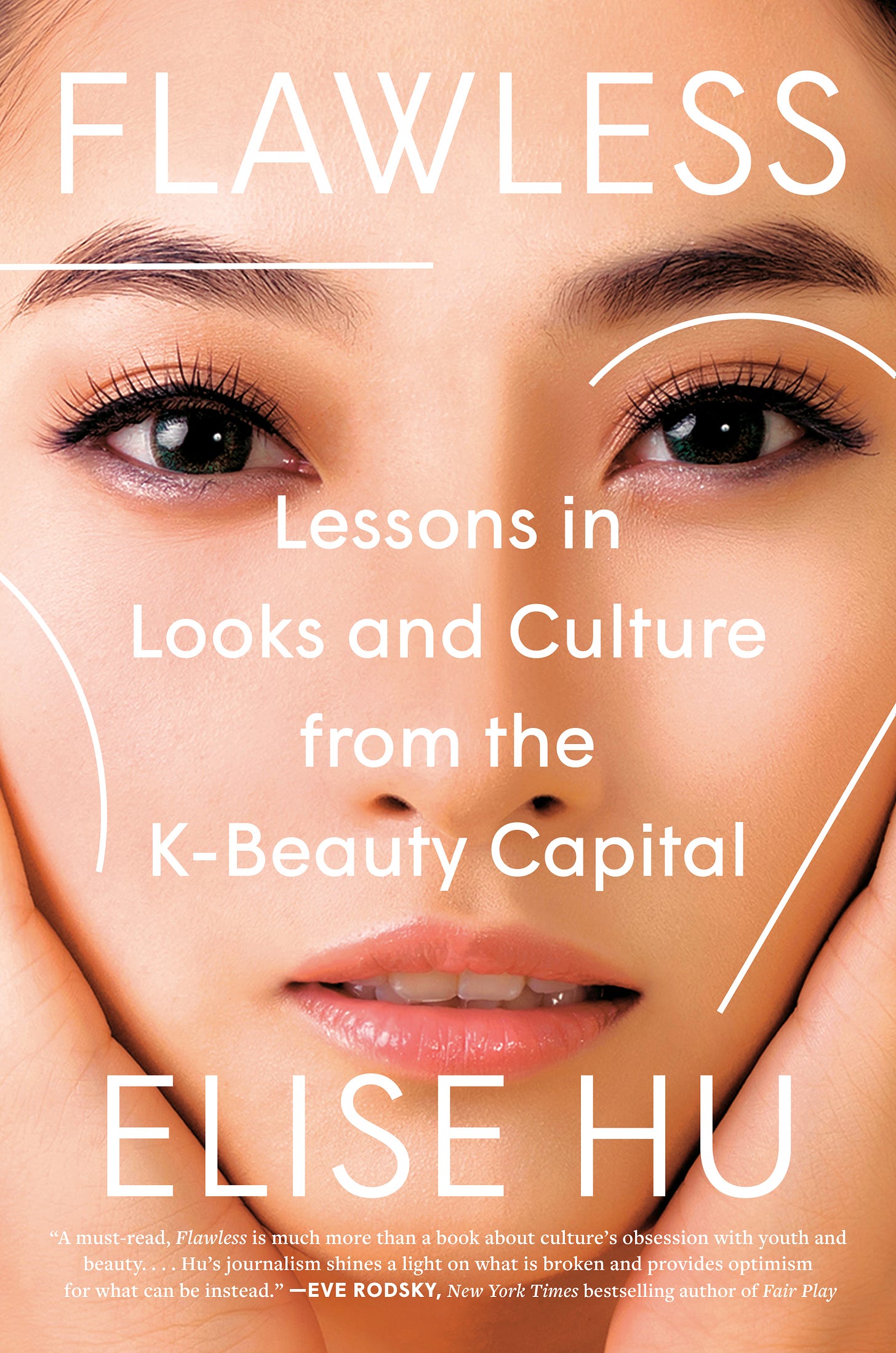

Elise Hu’s Flawless: Lessons in Looks and Culture from the K-Beauty Capital of the world looks at how this understanding of the face as a fixable problem has become foundational to the Korean culture and economy. Some of that culture is the wages of colonialism, some is connected to Korean discourses of modernization, some of it has to do with a stubborn persistence of deeply patriarchal values. But none of it is exclusive to Korea. Instead, we can think of K-Beauty as a lens through which to see the imperatives of global beauty cultures more clearly.

Hu, who is Chinese-Taiwanese-American, arrived in Seoul to serve as NPR’s first South Korea bureau chief in 2015. Flawless tells the story of becoming acquainted with the exacting standards of K-Beauty culture, processing her own judgment (of others and of herself), and figuring out what it means to parent within that culture. It’s an incredibly readable mix of first-person narrative of life in Seoul, rich cultural history, analysis and introspection. I loved it, and if you share the same fascination and ambivalence around beauty culture and serum culture in particular — you will too.

You can follow Elise Hu on Instagram here and buy Flawless: Lessons in Looks and Culture from the K-Beauty Capital here.

A lot of Culture Study readers are familiar with K-Beauty — a multi-billion dollar industry that’s only getting bigger — but I’m hoping you can tell the larger readership just how big this industry is, and why and how it developed the way it did in Korea.

Gosh, K-beauty is huge. South Korea is now the third largest exporter of cosmetics and skincare in the world, behind the US and France. It exports a higher volume of cosmetics than smartphones! Korea has the most plastic surgeons per capita on the planet — no other country comes close. And so many of the aesthetic trends we’ve been introduced to in recent years — “dewy” or “glowy” skin, multi-step skincare routines, perms for men — have all come from Korea.

The growth of K-beauty (and I include not just skincare, but also lights, wands, injectables, laser treatments and cosmetic surgery) happened alongside the meteoric expansion of Korean pop culture. K-pop, K-drama, Korean film, and gaming. The history is fascinating. In the 1990s, the South Korean state was looking for new economic engines and focused on the tech sector, building out a broadband infrastructure way ahead of its time and offering the fastest internet in the world. On a parallel track, a government report indicated that if Korea could make a blockbuster on the scale of Jurassic Park, the economic impact would rival the sales of 1.5 million Korean manufactured cars. So the public and private sectors invested in making visual culture in the form of films, drama and music videos, driving Hallyu, the Korean wave, which projected Korean “coolness” across the region, and eventually, the world. Just when the wave seemed like it was weakening around 2005, 2006, YouTube was invented, and digital video changed the whole game.

K-pop especially has served as a running advertisement not just for Korean beauty standards but also the aesthetic upgrades to make it possible. So in the same way a K-pop star will wear a certain lip tint and it will explode in popularity, an idol could get jawline surgery and popularize an entire jaw-reshaping procedure.

The aspirational beauty ideal, the thing that all of these beauty treatments are oriented towards, is K-Pop stars — and as you point out in the book, that look is itself as sort of “optimized” look. It’s in the same broad genre as the similarly optimized look of the Kardashians’ Instagram look, and has no space for the sort of uniqueness that was at the heart of so many classic stars’ looks (Bette Davis’s eyes, for example, or Julia Roberts’ smile). Can you say more about the specifics of this ideal, and what about it makes it feel so particularly aspirational in this cultural moment? Like what is going on with DEWY?

The specifics of the ideal include alarming thinness — a 50kg standard, with only a little leeway for height differences. Then it’s long luscious hair, porcelain white, creaseless skin, a delicate nose, big eyes, that glowy skin, and a soft, “V-line” jaw. There’s no singular explanation for the standards, but they are intertwined with geopolitical history. The double eyelid surgery has roots in both Japan (which brutally colonized Korea) and in America (whose troops occupied the South). The higher nose bridge and V-line jaw are mainly achieved through plastic surgery, and cosmetic surgery itself is born out of war — it emerged as a way to correct battlefield disfigurements. Fair complexion is a class performance dating to earliest dynasties, where the aristocrats who could afford to stay out of the sun were the palest, and aspirational for lower classes.

Taken together, what makes the look feel particularly aspirational in this moment (and I would say this is true of the Kardashian look, too) is that the current ideal only seems achievable if you put in a lot of work and money. To me it looks more and more cyborgian, like an AI image or a metaverse character. To get the kind of smoothness or fuller lip or perfect nose as projected by Lensa (or insert whatever AI app is big next) requires time and energy, and often medical skill of professionals. A lot of effort is required even to maintain a youthful glow! When we think of the body as malleable (and therefore upgradeable by biotech advances), it can become a project that can be worked on, forever.

One difference between the reigning American beauty standard and Asian ones is that Americans are a lot more made-up (I’m thinking of the Bold Glamour filter on TikTok, as an example). Many Koreans would consider it gauche to appear like you’re wearing heavy makeup. Their aesthetic is more of a “no makeup makeup” standard. But that’s just affecting effortlessness out of a lot of effort.

Can you tell us more about ‘lookism’? It feels like a sort of “saying the quiet part out loud” (re: people and companies judge and value people according to their looks). Since it was made technically illegal in Korea, how have organizations maintained lookism standards? And what are the reverberations when it comes to women’s place and power in the Korean workplace and larger societal inequities?

Lookism is appearance-based discrimination. It includes anti-fatness, and it intersects with sexism and racism. Professionally, headshots were often required on resumes (for any position, not just acting or modeling), and it’s still happening despite a law to stop it. In dating, matchmaking agencies rank clients on a set of “specs” that include height, weight, hairlessness, bra size, and a certain “cuteness,” or aegyo. I was stunned that the passport photo places automatically touch up your picture — smoothing skin and fixing flyaways or thinning your jaw line digitally.

We also have lookism in the US, but don’t label it explicitly. I mean, who among us hasn’t been teased about our looks? But, as you mention, I think societally we Americans try to gloss over it with talk of body positivity or saying “it’s your insides that count.” But we can’t pretend that there isn’t a pretty privilege and by extension, an ugliness cost, and South Korean society just openly acknowledges the privilege and situates “looking good” as a matter of personal responsibility. So if you don’t put in the work to look better, it’s a personal failing or you’re lazy.

The requirements of women are way more constraining than they are for men, in a society that’s already heavily patriarchal. I was shocked to learn that despite being one of the richest and most advanced countries in the world, South Korea’s gender pay gap, women’s labor participation rate, and the percentage of women in leadership positions are the worst among the developed nations in the OECD. One Korean company listed 20 appearance requirements for women, detailing how to look from head to toe, while men were instructed only not to wear mismatched suits. It’s illustrative of how beauty culture presents a structural inequity — requiring not just a second shift of household and childcare labor, but a third shift to walk the tightrope of appearance standards. And of course, it’s awful to conflate appearance with worthiness in the first place.

There’s a lot of ambivalence in the book that feels very familiar to me — in the intro, you write that as you were surrounded by this culture during your time as the bureau chief in Seoul, you felt strongly about resisting the pull to somehow “perfect” your face, but also absolutely bought the foot masks that made your feet feel like the bottom of a baby’s butt, and felt the continual pull of a billion serums, in part, as you write, because you were “attracted to the prospect of improvement.”

How has your ambivalence changed character over the course of the last eight years, through the move to and away from Korea, through Covid and your daughters growing up…..and also through the course of reporting this book? (the scene after you get Botox and you realize you couldn’t smile as wide is really going to stick with me)

That I vacillated so much in the pages is reflective of the complexities inherent to beauty culture. Our physical appearance gets conflated with the self (even though the concept of the self is so much more nuanced and richer than exteriors), and so a lot of us have internalized the notion of self-care as skincare, or costly treatments. That means there’s a thin line between nurturing our bodies in a way that is caring and sensual, and falling into extractive beauty work that benefits powerful interests.

Looking back on my first night in Seoul, I can’t believe how hard I was on other people, how judgmental, of women I saw with their post-op bandages. I thought of it as vanity, when now I understand their decisions to modify their bodies as totally rational for a broken system, and we should challenge the system instead of judging the woman. As a mom of girls, I’ve really endeavored to a) keep them away from social media for as long as possible and b) model for them, showing instead of telling, that our bodies are instruments for doing and feeling, and not ornaments for the gaze of others. That’s incredibly hard in an increasingly visual and virtual culture. But I don’t think we get to cultural change without a critical mass of us shifting our perspective in our own lives.

Throughout the book, a sentence from the intro stayed with me: “for those with the money to self-optimize, what kind of relationship with ourselves—and one another— are we ultimately pursuing?” This is the real “so what” of the book, I think, and I would love to hear you talk a bit more about where your writing and reporting led you.

The short answer is, we need a kinder relationship with ourselves, and by extension, a kinder relationship with each other. Your work on hustle culture and burnout informed my thinking in that I see beauty culture as hustle culture that’s reached into our bodies. Hustle culture as applied to disciplining or modifying our bodies isolates us from one another because we end up in competition, looking over our shoulders, and scared to ask for help when we need it. It’s a recipe for inequality and marginalization on one end, and anxiety and exhaustion across the system.

If we look to nature as a guide, the foundation of a well-lived life and a healthy social ecosystem is actually built on mutual care. So just as we millennials (with enough privilege to do so) need to remap our relationships with work, we can also remap our relationships with aesthetic work. I learned to take a beat and reflect on the ways that we almost automatically adhere to the notion that our worthiness boils down to our looks, and from there, began to untangle that knot. Liberating ourselves from appearance shame is an issue of bodily autonomy — and a matter of social justice — because it informs how we can show up in the world and participate in it. ●

You can follow Elise Hu on Instagram here and buy Flawless: Lessons in Looks and Culture from the K-Beauty Capital here.

If you enjoyed that, if it made you think, if you *value* this work — consider subscribing:

Subscribing gives you access to the weekly discussion threads, which are so weirdly addictive, moving, and soothing. It’s also how you’ll get the Weekly Subscriber-Only Links Round-Up, including the Just Trust Me. Plus it’s a very simple way to show that you value the work that goes into creating this newsletter every week!

As always, if you are a contingent worker or un- or under-employed, just email and I’ll give you a free subscription, no questions asked. If you’d like to underwrite one of those subscriptions, you can donate one here.

If you’re reading this in your inbox, you can find a shareable version online here. You can follow me on Twitter here, and Instagram here — and you can always reach me at annehelenpetersen@gmail.com.

David Gates’ poem today is particularly relevant: https://www.instagram.com/p/CsoKPkCOtk-/?igshid=ZWQyN2ExYTkwZQ==

Yes, I have good skin

it keeps the rain out and

vital organs in

I'm not pretty. This isn't me being humble or self-deprecating. I don't perform the labor of prettiness. It makes people mad! I've always had a really grudging and conflicted relationship with this stuff because I know my career and pay are suffering for it but I still can't bring myself to, uh, do anything about that.