This is the midweek edition of Culture Study — the newsletter from Anne Helen Petersen. Last month, I wrote about the millennial vernacular of fatphobia. Today, historian Angela Tate is here to talk about negotiating the images and ideals of the ‘90s and 2000s as a Black woman — and the overwhelming whiteness of eating disorder treatment.

Paid subscribers, your supports means I’m able to pay these writers an above-industry rate for their analysis. (If you’d like to support future guest writers, here’s how to subscribe). Content Warning: This post discusses disordered eating and body image.

Eating disorders are for white girls.

That is the message I received from the countless teen and women’s magazines I so eagerly consumed as a young adult. Jane. Seventeen. Teen People. CosmoGirl. Thin, lanky, straight haired white models and celebrities stared at me from hundreds of pages telling me the best ways to make low fat yogurt taste better, or how to combat a muffin top while wearing low rise jeans, or how to pose to hide any hint of a double chin in candid photos.

White millennials share stories about how these magazines (and other forms of media during the Y2K years) shaped their perceptions of their bodies and their diets. But as a Black millennial, I rarely saw enough of myself in these magazines to even have an awareness of (or a vocabulary for) how much I was also affected by diet culture.

The popular perception is that Black girls and women were and still are unaffected by disordered eating and body insecurities—my formative years were, after all, the era of Beyonce proudly claiming to be “Bootylicious” and loving Popeyes chicken too much to worry about dieting, and the era of video vixens like Melyssa Ford and Buffie the Body.

When friends or family told me to lose weight, it wasn’t to get skinny, but to whittle my frame down to highlight the assets—literally—that were the only phat thing I needed on my body.

Which is why, when the intake diagnosis at the Intensive Outpatient Program (IOP) classified me as having an eating disorder, I was shocked and appalled. I’d had issues with eating of course: I am a doctoral student under a lot of stress. I don’t often have time for three meals a day, much less paying attention to the nutritional value of what I eat. But I trusted the professional liaison between my university and my health plan while on medical leave, and assumed the eating disorder treatment was one part of my treatment for depression and anxiety.

Once in the program, I quickly grew concerned with the “quality” of my treatment. And as your average nosy person—or graduate student—I went on a hunt for more information about eating disorders and recovery. According to The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, there are three types of eating disorders: anorexia nervosa (AN), bulimia nervosa (BN), and Eating Disorder-Not Otherwise Specified (ED-NOS). But when I browsed through academic journals for more information, many authors admitted that literature on how eating disorders affect and manifest in African Americans remains sparse. Others that focused on Black women and other women of color had to work through existing biases and research shortcomings to describe the racialized and gendered dimension of eating disorders.1

The most recent overview of literature on this subject is from 1999 (!) and describes medical reports and research that exposed doctors’ biases against diagnosing Black women with eating disorders or flat out refusing to recognize the symptoms as fitting the medical standards — set by the study of white women — for anorexia, bulimia, etc.

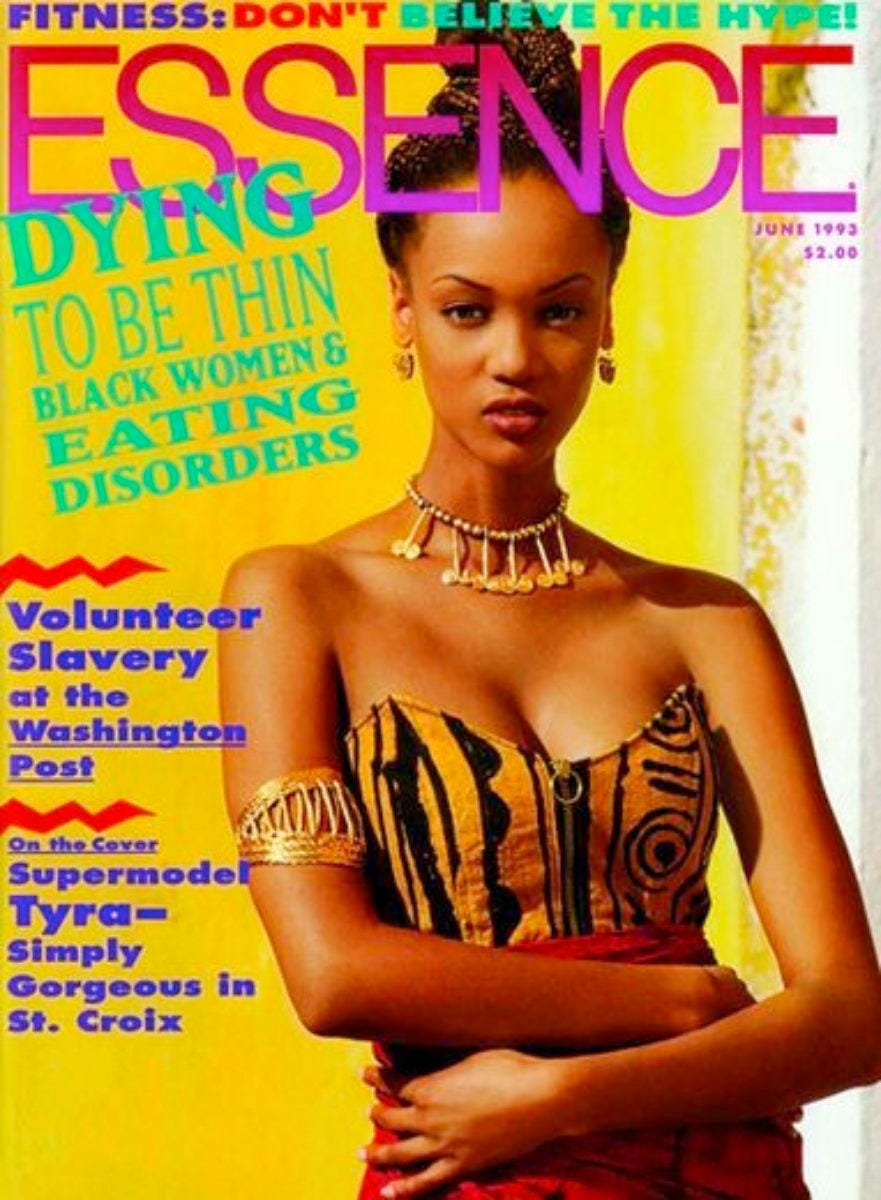

In the early 1990s, Essence Magazine, the leading periodical for Black women, compiled a study on eating disorders based on a survey they sent to 2000 participants. The resulting report flew in the face of continued assumptions about Black women’s body images—and how we view ourselves and Western beauty standards.2 (Comparing the Essence survey results to a similar survey in Glamour, the authors found that African-American women “appear to have at least equal levels of abnormal eating attitudes and behaviors as do Caucasians”)

If you look at the popular Black celebrities of the ‘90s, the thin, modelesque figures of Halle Berry, Whitney Houston, Lela Rochon, Tyra Banks, and others don’t appear too different from their white contemporaries (Julia Roberts, Claudia Schiffer, Shania Twain, et. al). Yet the myth persists that Black women do not suffer from eating disorders — and that if they do, they are perceived and treated in the same manner as white women. It doesn’t appear there are very many researchers, physicians, or treatment centers willing to tackle this gap in the literature.

My disordered relationship with food began in elementary school. It doesn’t look like it on the outside, but I grew up quite poor, with lengthy stints in family shelters, other people’s couches or spare rooms, and cheap, dingy motels as my mother took her three children and followed my father on his journey to find himself. Food was not something to think about, but to consume so my empty belly wouldn’t disturb my parents.

I think this is when I began to experience the digestion problems that were only diagnosed last summer. I used to wake up in the morning nauseated and bloating, but scarfed down the free breakfast at school because we usually had a long commute— half walking, half on the bus—from wherever we lived to school. Those TV images of mothers cooking hearty breakfasts was just that—something on TV. If I didn’t eat breakfast, no matter how horrible I felt, I wouldn’t have another meal until lunchtime, and dinner at home after that. And I had no choice but to eat whatever meal my mother could make on a tight budget, or was donated to us — at one point by a Salvation Army truck that stopped nightly at the motel we lived in when I was ages of five and seven.

As a teenager, I grew more canny about dealing with my eating issues. I was a cheerleader and ran track, and frequently stared enviously at the trim, lithe bodies of my white teammates whose shapes seemed to reflect their stable, secure, and well-adjusted homes. They weren’t ever homeless. They were never on food stamps. They didn’t have to worry about where they’d lay their head every night. They had the freedom and ability to live up to the beauty ideals that flickered on the TV screens and dominated the pages of teen magazines. If I could only find some peace, I thought, then I would be thin, fit, in shape, slim.

My mother projected herself as all-seeing and all-knowing, attempting to wrestle some control over a life she lost early on. (She’d married at 20, and the grasping hands and greedy squabbles for attention of three young children by 25 had to be an abrupt loss of identity). With only some college education and minimal office skills, her preoccupation with making money and not getting fired only created more instability. She worked long hours for little pay, was frequently passed over for promotions, and when fired from a job, had to find a new position that would overlook her lack of degrees in a world that was rapidly valuing a Bachelor’s Degree in [insert major] over a decade of work experience as an executive administrative assistant.

She never did see my insomnia, the nauseated mornings, or the binging and starvation. She did see my weight, however, and she frequently commented on my inability to find a boyfriend or a husband if I didn’t initiate an exercise plan. A husband would rescue me from the fate to which she’d resigned herself. She was by then long divorced from my father, still poor, and single for long periods of time periodically broken up by toxic dates. I grew up with stories of her athleticism and how my hatred of P.E. classes would have made her despise me if we’d somehow been in the same generation. I enjoyed the sports I did play, but I was never invested. The value judgments she placed on my athleticism ensured I never would. But the moments where I starved myself were greeted with approval until, after age 24, my teenage metabolism started slowing down and the weight wouldn’t budge.

Ten years later, I was miles and miles away from home, slowly climbing the ladder in a career I loved, but still plagued by cycles of self-loathing and anxiety about my body, still certain that once I found some peace, I would be thin, fit, in shape, slim. (As an aside, I only feel somewhat comfortable sharing my story because I’ve fallen out with my mom several times since beginning my journey to recovery. For so long, my silence helped her sell my level-headedness and success as proof of her own superior skill as a mother. She now struggles with accepting that she isn’t a Superwoman and my self-image took a beating while striving to meet her standards).

The therapist, nutritionist, and group therapy leader at the IOP never heard any of these stories. From the moment I was added to my treatment group I was alternately ignored or hypervisible as I stared at a video conference screen where every box except mine was filled with a very young, thin, white woman. The story prompts and pop culture references the group therapy leader created to encourage patients to share things about themselves had little to do with my life.

I didn’t develop an eating disorder solely to be thin, or because I hated food. I often felt guilty and ashamed for my eating disorder not expressing itself the way everyone else’s was. Even worse, the nutritionist and therapist assigned to me refused to believe my relationship with food and eating. At one point, the therapist refused to make eye contact and smirked as I attempted to explain the treatment plan was not working for me.

They were all white women, by the way.

After three weeks of being dismissed and belittled, I reached out to my university counselor. They were shocked—they hadn’t recommended me to the IOP for an eating disorder. Apparently, the treatment center decided that is where I belonged based on my intake survey. The counselor apologized, and said that if they had done so, they would have prepared me to enter a space that was dominated by cisgender, thin, young white women.

As a graduate student, I had already experienced the lack of care and intentionality that comes with being not only a Black woman, but a working-class Black woman in a space that also was historically not made for someone like me. I had already spent years navigating a model based on the lifestyles and culture of cisgender, educated, middle class white men. But again, as a graduate student, I am trained to tackle thorny issues on my own and make my own argument, with impeccable support and citations. Armed with the knowledge that the IOP treatment was incompatible with my needs and lacking in relevance, I immediately emailed my assigned therapist, nutritionist, and group leader to begin my exit from the clinic.

Shockingly—or not—they refused. As someone with disordered eating, I could not possibly advocate for myself or, more importantly, for my own body. A body they never saw over Zoom, nor took the time to get to know in their refusal to stop and examine why their training only centered cisgender, thin, young white women. At one point, the therapist was outrageously hostile to me asserting my own agency in the treatment process. But they were all smiles when my university liaison scheduled a meeting to force them to allow my exit from the program.

In the end, I spent about three and a half weeks in IOP for my eating disorder. It seemed longer, based on how miserable and disturbed it made me. The most horrific part of the experience was being made to feel insignificant in a moment where I most needed to be seen and heard.

The research on eating disorders continues to marginalize Black women. Even when we are present in the room, we are rendered invisible at best, and race neutral at worst. There is no room for the complexities of being Black, a woman, and disordered. Western beauty standards and standards of femininity place Black women on a pedestal—we are bootylicious, fierce, in command, queens—while also discounting that we can suffer, and that our suffering is just as valid, painful, and in need of treatment as white women.

It took a few months to get over the trauma of my experience, and at first I dealt with it through making jokes about the neglect and having to practically break out of the IOP. I feel enraged and slightly bitter at the way other health professionals ignored and downplayed my other physical health issues when I was being mistreated at the IOP. Today, the widespread nostalgia for the late ‘90s and early 2000s triggers my current thoughts about eating and my body, especially when I flick through episodes of Girlfriends on Netflix, and remember just how many messages about thinness and attractiveness were projected at me—at our entire generation of Black women.

Bootylicious Beyonce and video vixens may have touted a love of curves and being thick, but they still wore the low-rise jeans, bandana tops, skin-tight bandage dresses, and velour sweatpants aimed to show an “acceptable” amount of curvyness. The few Black models who frolicked in editorials in Seventeen’s prom issues or mingled with my latest celebrity crush were no different in body type than white models—which I often internalized as a condition of being acknowledged by mainstream media.

It’s also no coincidence that Brandy, one of my favorite singers, only shared that she suffered from an eating disorder a decade after her heyday as a teen R&B sensation. Her dwindling frame was never included in the hundreds of teen magazine articles about disordered eating.

She went unseen and unrecognized. I was unseen and unrecognized.

Because eating disorders are for white girls. ●

Angela Tate is a part time Midwesterner due to graduate school, a part time Californian by birth, and a part time DMV resident by upbringing. When she's not wrestling with a dissertation, she is wrestling with cats and a belated obsession with the MCU. Find more information about her extremely busy life at www.atpublichistory.com

Recommended Further Reading:

Roxane Gay, Hunger

Nettie Reeves-Lewis, Through Thick and Thin and Thick Again: A Black Woman's Journey With BED

Stephanie Covington Armstrong, Not All Black Girls Know How to Eat

Sabrina Strings, Fearing the Black Body

If you read this newsletter and value it, consider going to the paid version, which allows me to pay writers like Angela. Another perk: weirdly fun/interesting/generative discussion threads, just for subscribers, every week. The other perk: Sidechannel. Read more about it here.

If you are a contingent worker or un- or under-employed, just email and I’ll give you a free subscription, no questions asked. If you’d like to underwrite one of those subscriptions, you can donate one here.

If you’re reading this in your inbox, you can find a shareable version online here. You can follow me on Twitter here, and Instagram here. Feel free to comment below — and you can always reach me at annehelenpetersen@gmail.com.

Rothstein, Lauren A., Tracy Sbrocco, and Michele M. Carter. “Factor Analysis of EDI-3 Eating Disorder Risk Subscales Among African American Women.” Journal of Black Psychology 43, no. 8 (November 2017): 767–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095798417708506; Eating Disorders; Studies from Graduate School of Psychology Have Provided New Data on Eating Disorders (Spirituality and eating disorder risk factors in African American women) 9 December 2019, Mental Health Weekly Digest; Becky Wangsgaard Thompson. “‘A WAY OUTA NO WAY’:: Eating Problems among African-American, Latina, and White Women.” Gender & Society 6, no. 4 (December 1992): 546–61. https://doi.org/10.1177/089124392006004002; Amy M. Mulholland, and Laurie B. Mintz. 2001. “Prevalence of Eating Disorders among African American Women.” Journal of Counseling Psychology 48 (1): 111–16. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.48.1.111; Nikel A. Rogers Wood and Trent A. Petrie. 2010. “Body Dissatisfaction, Ethnic Identity, and Disordered Eating among African American Women.” Journal of Counseling Psychology 57 (2): 141–53. doi:10.1037/a0018922.

Andres J. Pumariega, Carl R. Gustavson, Joan C. Gustavson, Patricia Stone Motes & Shawnya Ayers (1994) Eating Attitudes in African-American Women: The Essence Eating Disorders Survey, Eating Disorders, 2:1, 5-16, DOI: 10.1080/10640269408249094

The US healthcare system is a con game and a racket, but it is never so evil as when it gets a Black or brown person in its clutches. Tate's account is deeply chilling.

In general, buyer beware on eating disorder treatment programs. (I myself am in a 12 step fellowship for compulsive food behavior.) I have heard some good anecdata on The Emily Program out of the University of Minnesota, but I have no personal experience. And I also don't know if those who recommended it were all white.

hello Angela! thanks so much for sharing your story. I'd typed out some other thoughts, but deleted them as they were still partially formed. regardless, know you're not sharing into the void