"I Found All Sorts of Dirt Immediately"

The stories families tell about themselves

I’ve found myself increasingly interested in the stories we tell about ourselves — how those stories get softened and sharpened, and how the story of who someone was, and what they did, and why it mattered gets passed through generations. Maybe this is just part of the process of getting older, but I also think it’s part of the process of getting older as someone who does cultural analysis. Star images tell stories about who we are and what matters in a particular moment; so do movies and songs and romances and sci-fi television series. They reflect visions of our values and our ideologies. Of course the stories we tell about ourselves and our ancestors do as well.

Earlier this year, I talked to Rebecca Claren about her book The Cost of Free Land: Jews, Lakota, and an American Inheritance, which grappled with the stories her relatives had passed down about homesteading Lakota land in South Dakota. As Clarren put it, “This book really started with three questions: What are the stories we tell in families? What are the stories we don’t tell? And why don’t we tell certain stories?”

If you apply those questions to your own family — especially the last two — the answer is usually a variation of the same handful of answers: some stories remain untold because they are unspeakably sad. And some don’t get told because they involve unspeakable deeds done to obtain or preserve power.

Jessica Goudeau’s We Were Illegal grapples with similar questions, only her story is centered in Texas and her family’s narrative that the family had “always” been there (and deserved to be there), even though that was very much not the case. The book is written in a really innovative way, with each part focusing on one relative who lived through a period of great societal change or upheaval. It’s wildly engrossing — but the way Goudeau frames these revelations, particularly in the history of Texas, is also incredibly clarifying. Keep reading, and you’ll see exactly what I’m talking about.

As a way of introducing readers to the book’s project, I thought we’d start as you do in the book: with the epigraph.

“About the difficulties of Texas: Love does not require taking an uncritical stance toward the object of one’s affections. In truth, it often requires the opposite. We can’t be of real service to the hopes we have for places—and people, ourselves included— without a clear-eyed assessment of their (and our) strengths and weaknesses. That often demands a willingness to be critical, sometimes deeply so.”

That’s from historian Annette Gordon-Reed, and I’m hoping we can use it to talk about 1) how you began to conceive of the book as a whole, and how you rooted it in your family’s own history and 2) the position you took in doing this work — and why it matters.

This book began as a Teen Vogue article published in 2017, right before I sold my first book, After the Last Border: The Story of Two Families and Refuge in America. The idea that my own family’s migration might be considered “illegal” by today’s standards (crossing an international border without the proper documentation) was something I couldn’t stop thinking about while I wrote that first book about two former refugees, one from Myanmar and one from Syria. The core ideas in We Were Illegal are rooted in my reporting on refugees, asylum-seekers, and undocumented immigrants from those years.

I didn’t know much about my family’s past other than a handful of stories and the fact that all four sets of my great-grandparents ended up in Texas. Even that lack of knowledge was a presence in my reporting: I grew up in Texas with the myth that we — my family and others like us — were here, had always been here, and deserved to be here. We were the unquestioned center, the rightful owners. This land was our land.

After the Last Border was supposed to come out in April 2020, about three weeks into the global lockdown; Viking (wonderfully) pushed it back until August 2020, which left me with several months at home, very keyed up with nothing to do. My editor at Viking had expressed interest in an expansion of my Teen Vogue article for my next book, but I was worried there might not be enough of a story to write a whole book, so I got on Ancestry.com to dig into my family’s history.

I shouldn’t have worried; I found all kinds of dirt immediately. One of my great-uncles was a Texas Ranger and, when I googled his name, the third link down was about how he helped cover up a mass murder. It got wilder from there: a relative of mine was a roommate of Stephen F. Austin’s in Mexico during the empresario (land grant agent) years in the 1820s; my relatives were part of the worst feud in Texas history; there’s a family secret that goes back eight generations to Sally Reese and the ten children she has with the improbably named Littleberry Leftwich. The problem I faced was choosing which of the stories I uncovered would eventually make it into the book; I ended up choosing relatives living through tumultuous times like this one.

As a lifelong Texan — I grew up here, returned for grad school, and stayed in Austin ever since — I worried about writing an unflinching book about Texas. People love to act like we’re all backwards and ignorant; I teach in a low-residency MFA program in Pennsylvania and inevitably, when I travel there every January and June, someone cocks their head and makes a sympathetic face and asks, “how’s Texas?” like I’m held prisoner in this state I adore.

Things have definitely shifted here; the politics are admittedly dark right now. I argue in my book we’re in the middle of a time of polarized extremism and that we’ve had other times like that in the state and the nation. One part of that extremism is a cultural and legislative move to control what versions of Texas history are taught in schools; all Texas kids take Texas History in 4th and 7th grades. There’s a big move to teach a triumphant and (I think) shallow version of history. But that’s exactly why so many of us need to stay and live out our values in Texas. And why we need to tell as many stories as possible, especially ones that uncover the truth of what really happened beneath the veneer of whitewashed histories.

It’s because I love Texas that I wanted to be a part of doing that work. Annette Gordon-Reed wrote that quote in her excellent book, On Juneteenth. My own work is in conversation with hers; it is imperative that someone like me — a white descendant of enslavers whose ancestors helped shape this state — join her and many others in telling the truth of what really happened.

It cannot just be the job of those historically and generationally affected by injustice to name that injustice; it’s incumbent on all of us.

I know it’s difficult to choose a single character/narrative from the book, but to give readers a feel for the really interesting way you approached this work, I’d love if you could pick one, tell us a little about them, and talk about the contemporary tension at work in their very historical story.

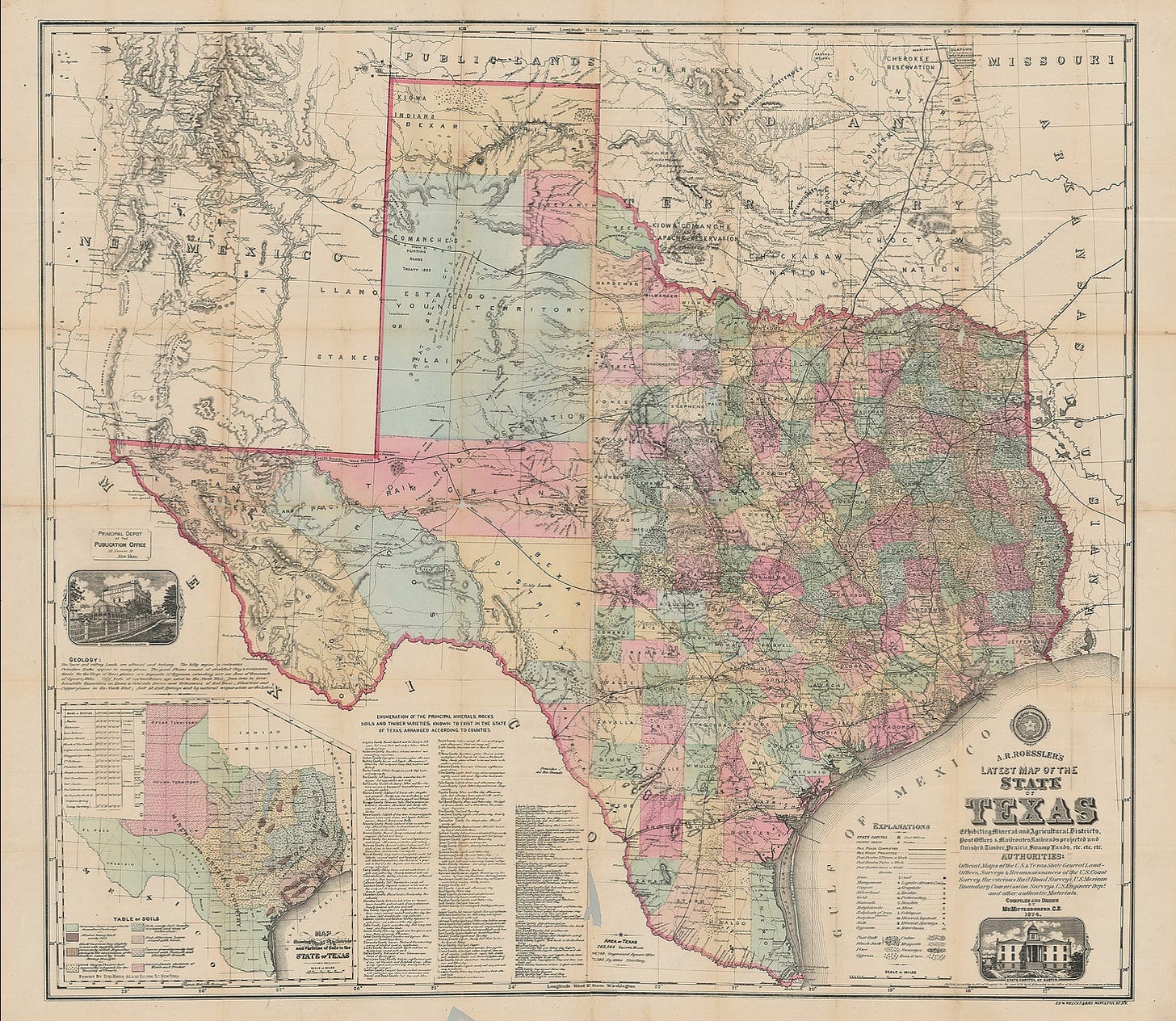

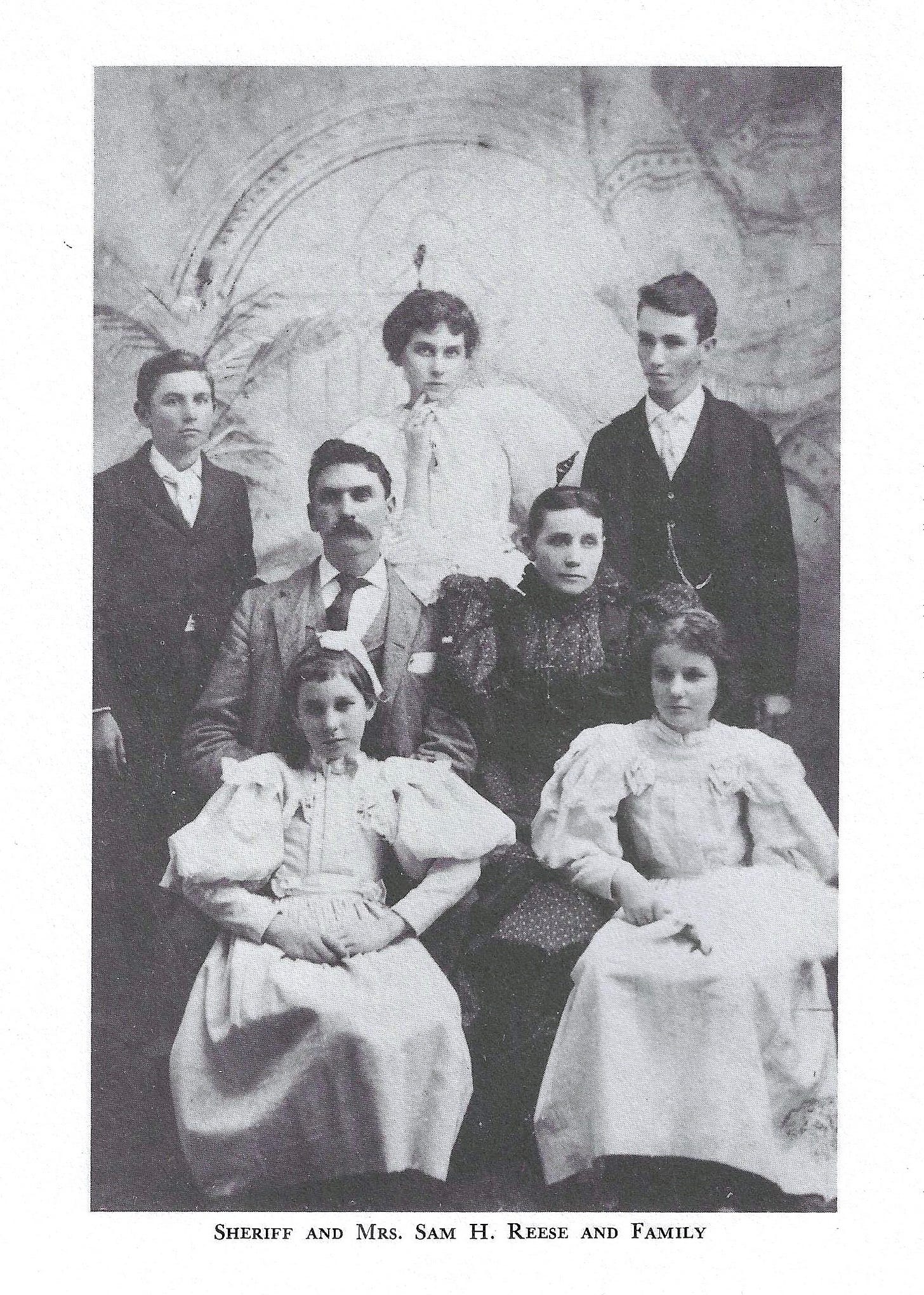

In Part 4, I write about my relatives during one of the worst feuds in the history of Texas, which took place at the end of the 19th century and beginning of the 20th. Here’s the tiniest bit of context: two families, the Staffords and Townsends, got in a big fight in the 1870s and started murdering each other in Colorado County, Texas. It was the Reconstruction Era, and the county had been a place where a lot of people were enslaved, leaving many newly freed Black citizens in close proximity to the racist people who recently owned them. There were enough Black voters that they changed the political dynamics of the county — the feud over families quickly became a feud over controlling the Black vote. The role of sheriff — an elected position — was highly prized, because it was basically a way to legally arm your side in the feud. Black people were pawns in this deadly political game.

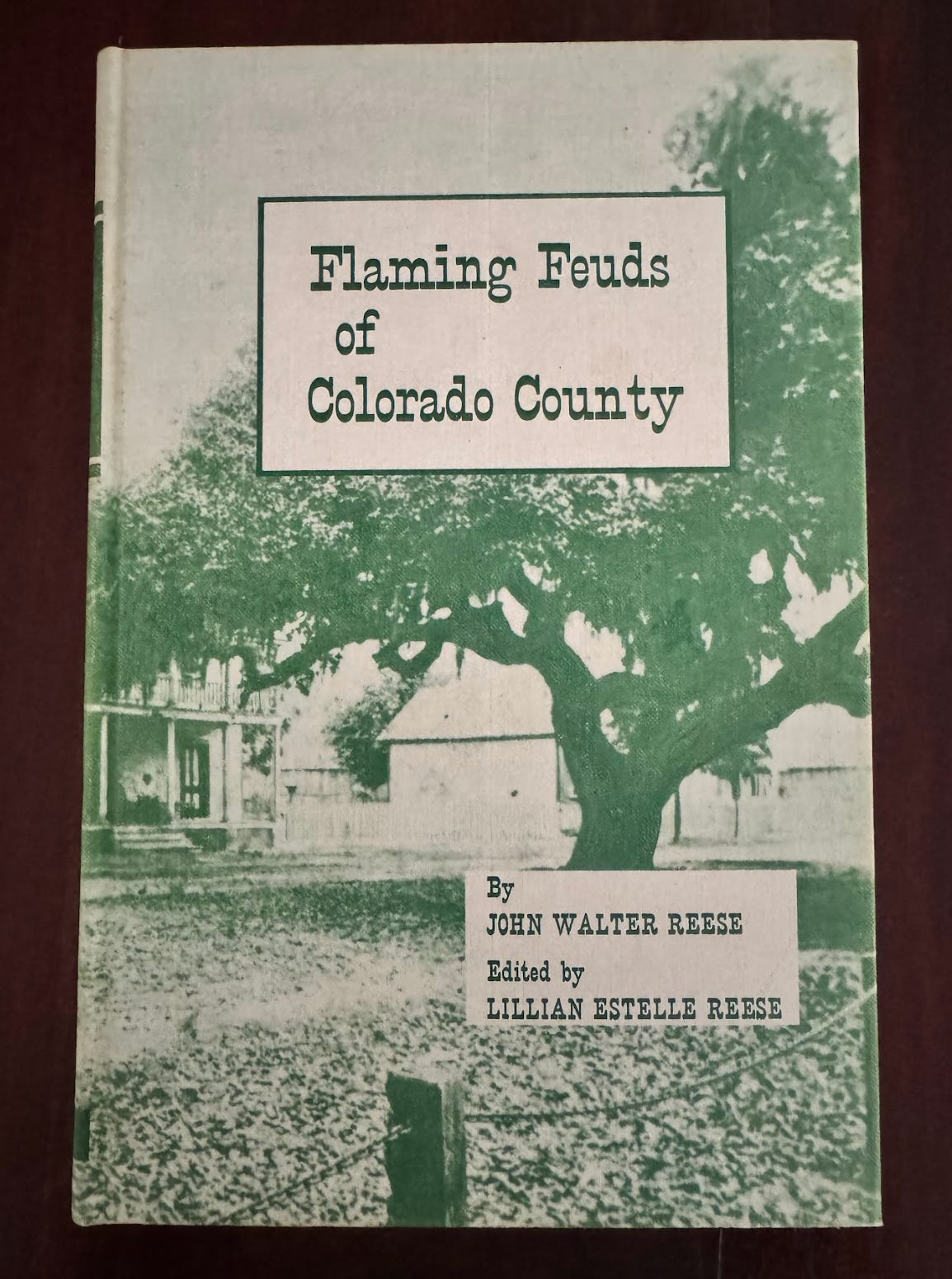

One of my distant relatives, Sam Houston Reese, married one of the Townsend daughters, became sheriff, and the Reeses got really involved in the feud. At the end, it was all about the Reeses—they were savage. Decades later, one of his daughters, Lillie Reese, wrote a book called Flaming Feuds of Colorado County about her father’s murder in the feud. Lillie is the person I want to talk about.

Flaming Feuds book is one-sided and biased; it was published in the 1960s, long after the feud was officially over. Almost a century after the feud started, there might not have been shootouts anymore, but people still spit on each other in the street. Lillie hung her father’s bloody clothes on her clothesline every year on the anniversary of his death.

She wrote the book to prove that her father’s actions in the feud were justified, and to clear her family name. But a historian named James Kearney, who grew up in Colorado County and still lives there, privately recorded the stories of a “Reese man” — a close friend of the family who participated in the feuds named John “Goep” Goeppinger. Goep’s confessions showed many of the stories Lillie tells in the book are lies.

Lillie was in the room when they plotted the murders of their enemies, and knowingly wrote a book claiming they had nothing to do with those deaths. In my book, I laid out the competing stories: Lillie’s version in Flaming Feuds, followed by the truth of what happened.

Lillie’s book is one of the most blatant examples of historical cover up I found. It might not seem like a big deal — an obscure book about a feud that hardly anyone cares about any more. But it was a clear example of how history is changed over time in a family, a community, a state, or a nation. And how the work in front of us is to go back and evaluate those stories, and then widen the scope to include the voices of the people affected (like the community of color in the county) or the people whose stories tell the deeper truth (like Goep, confessing to the murders my relatives ordered).

This isn’t just about history—it’s a kind of racist telephone game that happens in real time too. A recent example is what happened in Springfield, Ohio, where a woman posted on Facebook about a rumor that a neighbor’s cat was taken by Haitian immigrants living nearby. The story suddenly took on a life of its own and ended up a talking point in the presidential debate — and then resulted in threats against the Haitian community living there. Evaluating the story, deciding who benefits when a racist version of a story is told (the politicians who want an outraged base to vote for them), and then combatting that misinformation with the truth is imperative for all of us.

This is a big, broad question, but I’m particularly interested in it given your family’s relationship to the Church of Christ. What sort of narratives (of self, of group) did Christian settlers gravitate towards? I know Manifest Destiny is all over the place, but how did it intersect with other narratives of persecution, suffering, and “doing right?” How do you see the vestiges of those narratives at work in Texas today?

In the introduction, I call my Church of Christ family’s view of our place in the larger US and Texas history a “Great Absence.” I knew one side of our family history; I had a xeroxed copy of my family’s history from a distant relative we called “Uncle Sloman,” and it was an absolute delight to me. Uncle Sloman told the story of how a few families moved together from Tennessee to a town called Corinth, Arkansas. I loved the amazing names, like Minerva and Tacie and Bula (“a fine specimen of womanhood”), and the folksy stories.

My dad was the one who pointed out when I was older that the reason they were enslavers who had land available to move to in Arkansas was because of the Trail of Tears, and that all of the men of fighting age fought on the side of the Confederacy. As a kid, I thought of it as a story of “faith on the plains.”

That framing is important because the focus in our family stories was about how our family came to faith (the Churches of Christ in the 1830s) and then how that faith affected the generations (everyone has been Church of Christ until the last couple generations). Until my parents began to widen the stories, the passed down lore was NOT about how we took land from indigenous people, enslaved others, or benefited from oppressive systems. And frankly, the narrow focus was pretty great growing up: I loved Laura Ingalls Wilder books, and many others (did anyone read the Janette Oke series? Because whew, I have thoughts about that one!). I just assumed as a kid there was this bright legacy of faithful Christians doing what was right and living out their ideals across the plains for generations.

Because of the myth of this “Great Absence,” many of the stories passed down were about how we were “in this world but not of this world” (a phrase from a Bible verse). But my research showed we absolutely mucked around in “the world,” meaning we were involved in politics and colonialism and genocide and redlining and all of the things that shaped life around us. As Harris might say, we “existed in the context of all in which we lived.”

I know I’m not the only one to grow up with this “Great Absence” myth; that’s part of why I think Christian nationalists and others frame any criticism as persecution. Any criticism tarnishes the bright, beautiful stories people received from their families, schools, and church communities. It hurts.

I also think that’s one of the bases for the move in Texas and many, many other places to only tell “triumphant” historical stories. Politicians and advocates often frame any curricula that teach a broader version of history as “CRT” (Critical Race Theory; it’s not; that’s a graduate level course; it’s so exhausting). Texas is a place where Christian influence is strong especially among those in leadership. Some are just greedy and out for political power, but there are many people of integrity who truly think that a school curriculum designed to tell wider, more representative stories is put in place only to make white people feel guilty. They’re “persecuted” because the more robust version of history is outside of any narratives they’ve ever received.

But also, importantly, many of them change their minds. For the podcast I co-host, “The Beautiful and Banned,” we recently interviewed Courtney Gore, who ran for the schoolboard in Granbury ISD on the platform of removing “CRT” from schools, and then publicly changed her mind when she realized that students were just learning to be nice and help each other; she faced death threats and continues to speak out with real moral courage. The interview gives a truly fascinating insight into the debate around education and book banning around the country and how someone changes their mind (it airs on October 8).

One more quick thing: I’m so tired of one-sided portrayals of Texas, and Christians, and all kinds of groups; there are so, so many Christians who are aware of their past, who are thoughtful and welcoming precisely because of their faith, and who are doing this work deeply every day. I received most of the stories I write about from professors and historians whose faith compelled them to widen their views decades ago, including my parents; I learned from them to think critically and compassionately. Just like many Texans are doing this work in my state, many people of faith are leading the charge as well.

For the process nerds and historians in this group, because we are legion: how did you approach the archival research? How did you think about integrating archival finds with existing family lore (particularly from living or recently living family members)? And what was your biggest archival surprise?

I am so excited to speak with my people! This book was basically six dissertations’ worth of research in one book—all done within three years. I began on Ancestry.com trying to find credible stories of relatives involved in the history of Texas. I also researched major moments in Texas history I wanted to talk about and created an external timeline. I was also doing research in things like rosters from militia units in the Texas Revolution for known family last names (we have a lot of Joneses; please don’t get me started on those weeks of research). I cross-referenced any names that might be possibilities from those time periods with what I was finding on Ancestry to show that these people who were involved in Texas could actually be a part of my family tree.

Most of my research led to dead ends: there was one drummer in the Texas Revolution named John Reese and I was convinced for weeks he was a relative of mine; it turned out he wasn’t (he came from Wales) and I’m still sad because his story was incredible. I did, however, find a young man named Perry Reese whose father was a relative of another Reese line in Virginia and eventually wrote about his death in the Battle of Goliad.

My research was basically thousands of needles in moving haystacks. I hung up big bulletin boards in my office and printed up family lines and land grant deeds and copied pages from genealogies and all kinds of sources, and tried to make connections. One of my best friends called my office décor “conspiracy theory chic.”

All of this was online in the beginning because it was the pandemic and almost every archive was closed for most of 2020 and early 2021. That was hard in many ways, but also, during that time, a number of sources were either digitized or available publicly in a way they normally hadn’t been, which really helped me. (I also worked in a dual-credit program at the University of Texas to have library access--imo, a very good reason for a side hustle!). As I researched on Ancestry, I found there were genealogists whose work I trusted; some of them had websites or other ways to connect. I interviewed several; my favorite was a family genealogist named Sherry Finchum, who spent a week with me in Bedford County, Virginia doing archival research there. We dug through deed books and bastardy bonds and court cases and bailiff bonds and all kinds of stuff. Most of those records were original 18th-early 19th century sources, often just filmy pieces of paper in big folders. I still can’t believe they just let us touch them.

I was also telling not just my family’s stories, but the wider story of the people affected by their actions. And each time period I moved through had its own challenges: in the 1820s, I could rely on the letters and documents in an encyclopedic series about my relative, Robert Leftwich; one court case in the 1830s gave me some insight into the fates of family he enslaved, Polly and her sons. The 1850 and 1860 censuses included the names of freed Black people for the first time, and provided greater access to some of the descendants of people whose stories I wanted to tell. By the 1890s in Colorado County, there were reliable sources that named Black and Latinx families and gave details about their economic status or family relationships. The book ends in 1940, and by the time I got to that research, it felt indulgent—I had newspaper articles and court records and family stories and all kinds of sources.

I also did many first-person interviews. The most difficult was with the man, now in his 80s, who was a toddler when my great-uncle helped a sociopathic sheriff use a machine gun on his farmhouse to murder his grandfather and great-uncles, and then cover it up. That interview was awful and beautiful all at once.

One of the hardest things I’ve ever had to do as a writer was to take this enormous amount of information over four hundred years, and tighten and tighten and tighten it until these feel (hopefully) like highly readable, related stories that span centuries. I wrote a million drafts. My editor, Emily Wunderlich, and my agent, Mackenzie Brady Watson, who also edited portions of it (unusual but she’s the very best), were extremely helpful in that process, and I’ll always be grateful to them.

Having lived in Texas and spent a lot of time reporting there, I know you and I share many ideas about how Texas is at once utterly singular and that you can use it to unpack so many components of the American past and present (and future, for that matter). I felt moved by your description of your deeply rooted love for the state, but also recognized some of my own ambivalence in how I relate to my home state of Idaho and the political shifts that have seized it: there’s strong evidence that the politics of exclusion and fear have been there all along, I was just well-positioned to not feel them.

This is my long way of asking: why Texas? Why does navigating a way forward from, as you put it, this “precarious moment,” matter? What hard truths remain ignored?

As I argue over and over, this is not a book only for Texans. Texas is a microcosm of the larger republic. But Texas also is its own specific, delightful, frustrating, ridiculous, wonderful place and I wanted to write as a Texan about this land, these conversations, and this history with deep, deep love.

One of the things I realized in writing this book is, as Texas goes, so goes the nation. I noticed it first with the political shift that happened in 2015: Texas was unquestioningly a place that always supported refugees (I’d been working with refugees for almost a decade by then); we went from a state with the highest resettlement levels of any state but California to a place of staunch anti-refugee rhetoric almost overnight. Trump is most famous for it, but the language came from our senators and governor and others first. They combined anti-immigration language with refugee resettlement, and then the rhetoric spread throughout the nation. Then I noticed it with abortion legislation, and book banning, and legislation around medical care for trans kids, and so many other things that have become cultural issues, but are really policies about people’s bodies and lives and the values we pass on to the next generation.

For me, it was critical that this book about slavery and immigration be set in Texas. Our location along the border means questions of immigration are real and pressing at all times. I did not fully realize until I wrote this that the history of immigration in Texas is a history of slavery—Anglos came to Texas in the 1820s and 1830s, and then seceded from Mexico because they wanted to make money off of big plantations. The land in Texas was perfect for growing cotton, and the only way to make that kind of money was to enslave people to do the labor. Texas was its own country for nine years, and it remains the only country in the history of the world to protect the right to enslave people into its constitution. When Texans seceded from Mexico, they worked out a political playbook that then spread across the South a few decades later when the Confederacy was formed and the Civil War began. Juneteenth was one of many examples of Texans in power keeping the news of freedom from the people they oppressed. There are dozens of examples through history that showed that Texas leaders—often brash, in-your-face, and over-the-top—innovated political moves that spread throughout the country.

I think that’s happening again today. I’d personally love to read a book about the political history of Idaho or Wyoming or Florida. But there’s something about the myth of Texas, both within the state and outside of it, that changes the weight of our cultural conversations. Our political fights became the nation’s.

Or maybe that’s just my own pride, to think Texas is the center of it all—I am, after all, a Texan. ●

You can find more about Jessica Goudeau’s work here and buy We Were Illegal here — and check out her Substack, The Injustice Report, here.

This is something I have been wrestling with for the past several years.

Since the establishment of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission that explored the history of residential schools in Canada, I have been on my own personal journey of Reconciliation. I am descended from settlers and had close family members who worked in residential schools (as civilians, not clergy) and who participated in the Sixties Scoop. I know I am not alone; statistically I can't be, but few will admit it.

I don't know exactly what my family members saw or condoned or actively participated in. But I do know that understanding the truth has to happen before we can truly move forward. So that is how I have chosen to approach this with my own kids.

We are not our ancestors, however I do feel a tremendous duty to atone for the wrongs they helped perpetuate. I can hold the nuance and complexity of the situation and sit in the uncomfortable-ness and shame of it all. It pales in comparison to the generational trauma inflicted on our indigenous communities.

I can't wait to read this book. I have also benefitted from HOW THE WORD WAS PASSED by Clint Smith.

My comment is topic adjacent; as a Texan I really appreciate the reminder for the wider audience that the stories we tell about <insert literally any place> shape that place too. I was listening to a podcast recently where both speakers were gender-non-conforming, and both grew up in Texas in the 1990s. And they kept saying things like “as a queer kid in Texas”, where we’re meant to understand as “in enemy territory“. And as a straight kid in Texas a little older than them, I get why they would say that and why they would have felt that way! AND, I believe they were mistaking the era of their youth (post-AIDS America, Don’t Ask Don’t Tell America) with the geography of their youth (California in the mid 90s had a Republican governor, Texas had a Democrat, although neither actively supported LGBTQ rights). They let what Texas means to them today define what historical Texas is too. Which is not to say that historical Texas has been great either (as is clearly laid out in this book that I can’t wait to read), just that we should stop treating Texas as a caricature of conservative extremism when it’s not really that different from any other part of the US.

Pretending that California or New York or Pennsylvania are all that different from Texas is being naïve to the problems right under our noses.