"In reality TV defined by renovation, the self becomes settled."

Let's talk about Chip and Joanna Gaines

This is the midweek edition of Culture Study — the newsletter from Anne Helen Petersen. Paid Subscribers: If you haven’t activated your invitation to Sidechannel, email me for a new one.

I am obsessed with towns and their stories. This is what I miss most, reporting-wise, about the pandemic: going to a place and trying to figure out its layers of cultural sediment. Every story I write tries to do a bit of this, but I’ve done it explicitly in my features on the Nashville bachelorette scene and Waco, Texas, the backdrop and main character of Fixer Upper and the greater Chip and Joanna Gaines extended universe.

I remain deeply invested in analyzing the larger Magnolia project, for lack of a better phrase, and was recently blown away by an article in the Journal of Popular Culture that manages to approach Fixer Upper and its vision of Waco through the lenses of religious studies, space/place/geography, post-colonial studies, and architecture and design. “Prophets of Place: Centering Waco in the Shiplap Frontier of Fixer Upper” is truly my platonic ideal of an academic article: deeply interdisciplinary, beautifully written, accessible and rigorous.

It’s the work of Ph.D. student Rebecca Lea Potts, and I was thrilled when she agreed to talk more about her route to this work, Texas, her mini-shiplap dissertation, and the sort of Christian music that you JUST KNOW is Christian. I was enthralled by her answers and I think you will be too.

You have a really interesting path to your current research. Can you walk us through how you arrived at the work that you do, and how you ended up in a PhD program in Religious Studies?

I grew up in San Antonio, Texas, the only child of liberal, Anglo Protestant parents. My grandfather was a Baptist pastor, but my parents started going to a Methodist church and I was along for the ride. I went to Sunday school and youth group, but my rebellious phase started young and, by the fifth grade, it was a constant struggle to get me into church clothes and seated in a pew.

By the sixth grade, my parents and I came to a compromise: I could skip youth group and cut down on my church attendance if I went through the confirmation process. This process involved several classes, lock-ins, foot bathing rituals, and letters written to future selves, all of which culminated in a public baptism on Sunday morning. Our bargain strikes me as hilarious in retrospect. Like proper Baptists—who believe that baptism should be free and consciously chosen—my parents did not baptize me as a baby, but they seemingly saw no contradiction in coercing me into this sacrament as an angsty pre-teen. I got baptized in order to apostatize.

After my confirmation, I gave little thought to religion in general or Christianity in particular beyond the pitying scorn of an adolescent who already knows all there is to know. In high school, I was interested in movies and wanted to study film and media in college. But in my freshman year at Pomona College, Darryl Smith’s class, “The Holy Fool,” provided an entirely different lens through which to think about religion—one that included Afrofuturism, Russian novels, arthouse cinema, and sources both inside and beyond what I had understood to be the boundaries of religion.

In the summer of 2012, I moved to Austin and started working on the political campaigns of women Democrats in Texas and, within a few months, was thoroughly burned out and disillusioned with the politics writ large and small. I eventually got an entry level office job at a homebuilding company in Austin and, after a few months, I was offered a position as an assistant construction manager. This company builds high end production homes in Austin, Houston, Dallas, San Antonio, and, at that time, I was the only woman construction manager in Austin and one of two in the entire company.

After building several dozen suburban houses, I started working for a commercial construction company that built restaurants and bars. My first project was full scale renovation and addition of a restaurant overlooking Lake Travis. I survived that experience in large part thanks to Manuel Campos, a framer who I had met at my previous job and who agreed to work on this new project with me.

After finishing the restaurant remodel, my best friend and I took a trip to Italy, and I went to the Vatican alone, half expecting some kind of religious conversion that never happened (though I did spend a moody few days in Rome wandering around the ruins and listening to Carly Rae Jepsen’s E-MO-TION on repeat). I made the final decision to apply to Union Theological Seminary in New York City, where I eventually my Masters in Systematic Theology and the Bible and started my PhD in religious studies at Yale.

While making my way through Union, I realized that I could reconcile both parts of my professional life—construction and religious studies—in and through my work. Now I study religion and the built environment, focusing particularly on the landscapes, materials, histories, and aesthetics of the US Southwest.

Now I’d love to hear about your Fixer Upper story — how and when did you first start thinking about it? Your article is written in a way that (at least for me) immediately signals that you’re from Texas — the way you frame Waco as a pit stop is 100% how everyone, including people who grew up in Waco, did so in their conversations with me as well.

My HGTV obsession began in late high school and culminated in the purchase of several books about home design and the impromptu removal of louvered accordion doors in the kitchen (much to my parents’ chagrin—the doors never did function the same again). However, once I began working in construction in Austin, many of the shows I had enjoyed—like Property Brothers and Love It or List It—were, in their portrayal of clients upset about unforeseen construction issues, too close to home. The more and more I experienced the headaches, demands, and conflicts arising between myself, architects, clients, and the conditions of the building, the less and less I wanted to see those dramas on my screen. I gradually stopped tuning into anything other than Fixer Upper. This show had no angry homeowners and all the tears were tears of joy.

In Fixer Upper’s Waco, divisions between client, builder, architect, and subcontractors appear nonexistent. Every episode, Joanna adds and/or subtracts from the plans and Chip makes a joke and says, “I’m on it, babe.” In one episode, Chip gets an idea that it would be nice for the clients if they added a half bath off the living room. Joanna eagerly agrees and, just like that, it is settled, no client meetings, no pricing options, no frantic emails to the MEP engineer for the last-minute changes.

In the world of this show, builders never cut corners that lead to warranty issues, architects never give conflicting dimensions and point to the “verify in field” note when discrepancies arise, subcontractors never walk off the job, and engineers never give failing reports. Door and window packages are delivered accurate and on time, and, when it’s all over, the clients do not walk around with blue tape marking every paint scuff, jagged grout line, and floor scratch. I relished the fantasy of Fixer Upper, the way it made construction seem inexpensive and conflict free.

I was also bemused by Fixer Upper’s packaging and presentation of Texas to a national and international audience. (The sudden spotlight on Corsicana, Texas—where my parents grew up and where I spent many childhood summers and Christmases—in Cheer was similarly striking, though Cheer arguably offers a counter example to Fixer Upper since the place of Corsicana is deemphasized after the first episode.) To see Waco (where my parents and grandparents had lived as Baylor students) supplanting Dallas, Houston, Austin, and the nebulous space of west Texas cattle ranches and oil derricks as the locus of Texan iconography was, at first, largely humorous. On screen, a city widely regarded as a pit-stop between Austin and Dallas became an aggressively wholesome center of Texas design and identity.

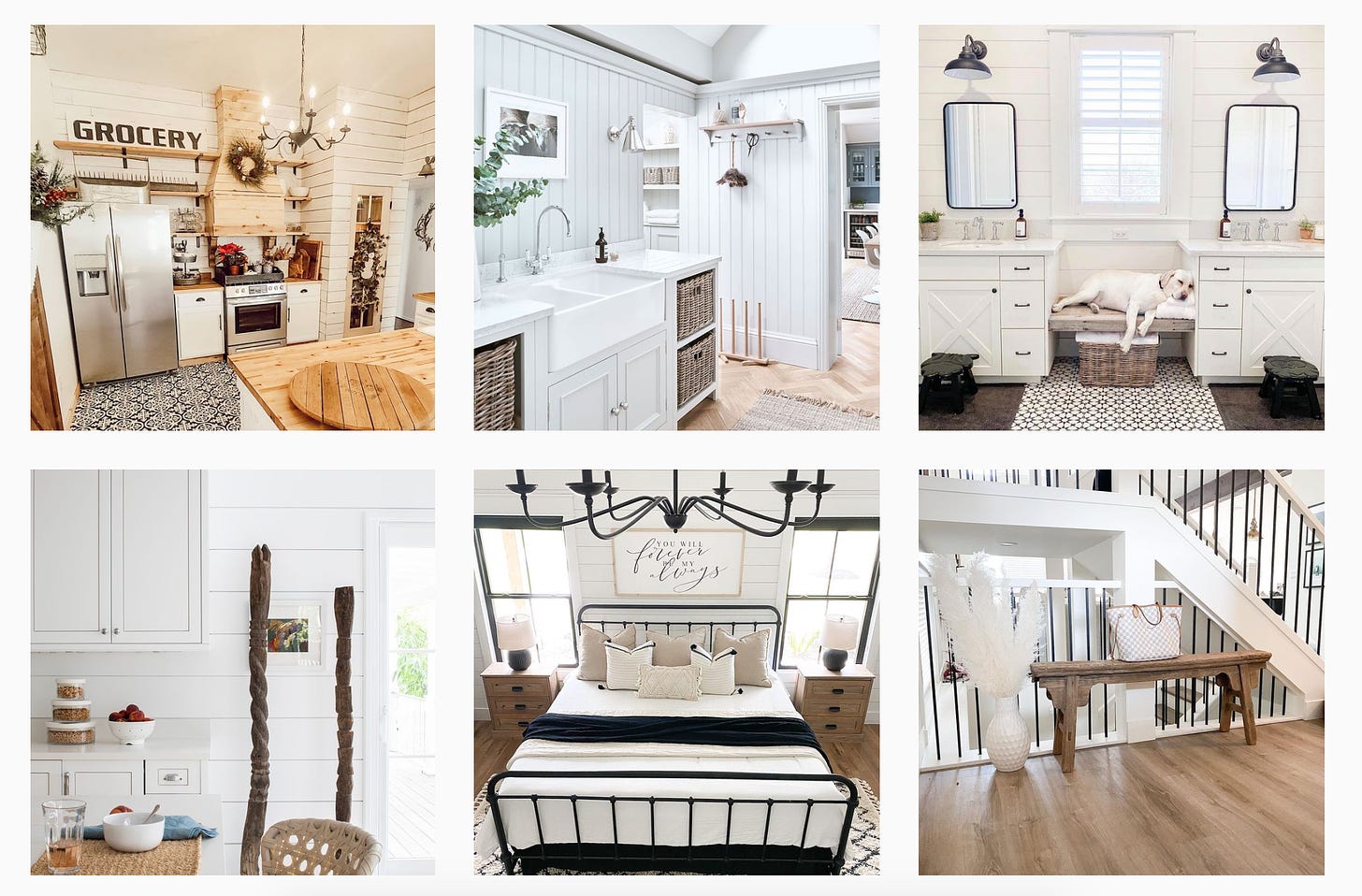

Where many cultural products have focused on the danger and emptiness that Texas landscapes and histories can imply, Fixer Upper purges unsavory associations from the state’s reputation. The Texas of Waco, as presented by Chip and Jo, is a frontier but a virtuous, picturesque, neighborly frontier. I started noticing a feedback loop between what the Gaines were doing on their show and the designs I was asked to build in Austin. When I moved to the Northeast and continued to see shiplap and barndoors in newly remodeled spaces, I knew I had to figure what was going on. How did the look and feel of Joanna’s Texas become so widely resonant and appealing?

I started writing about Fixer Upper in the fall of 2018 in what began as a somewhat unhinged fifty-page document. I couldn’t stop thinking about or talking about the Gaines and shiplap with everyone around me and it is a testament to the wonderfulness of my fellow grad students that they not only continued to hang out with me, but also engaged with, added to, and helped me refine what it was I was trying to say in this piece. This article was a hugely collaborative process, and my parents deserve a lot of credit for its final form. They read every draft and kept me spatially and rhetorically grounded—letting me know when I got too jargon-y and making sure I changed “baby cows” to “calves.”

This article is a site in which I begin to grapple with the conditions—the places, people, and media—that created me. As Sara Ahmed says, “it matters, how we assemble things, how we put things together. Our archives are assembled out of encounters, taking form as a memory trace of where we have been.”

In the piece, you argue that understanding Fixer Upper as a product of neoliberalism isn’t enough — that you need to position it within a larger frameworks of Christianity, colonialism, and the “settler past.” Can you talk more about that — and the idea that in “reality TV defined by individual transformation, the self becomes sovereign; in reality TV defined by renovation, the self becomes settled”?

I did not want to write a paper that used academic terms and values as the ruler by which to evaluate and eviscerate Fixer Upper. I wanted to write a piece that took the show seriously and used the Gaines’ own terms, ground, and materials as the lens through which to understand their work. It would be all too easy to write about and write off the show as a further instance of neoliberal self-sovereignty, but that critique does not attend to the material and ideological specificity of what the Gaines are up to and why they are so beloved and successful.

Unlike “theater of suffering” programming (Extreme Makeover, Queer Eye, Queen for a Day), Fixer Upper does not demand tales of woe or performances of dissatisfaction as payment for the clients’ “dream home.” In Fixer Upper, the logic of tragedy and failure that underwrites makeover programming is moved from individuals and their bodies and placed on and in the architecture of the home. The suffering subject is subsumed by the dilapidated house; the physical structure is made to perform the labor of exposure and crisis that is usually demanded of the guest/client/beneficiary. Fixer Upper allows the house itself to bear the woeful weight alone. The physical condition of the closet—too small, poorly lit, wrong location, moldy—takes the place of the client’s skeletons.

By arguing that Fixer Upper functions in a framework outside that of the typical suffering subject of reality TV, I am not implying that it disinvests from the logics of reality, makeover, and lifestyle television, which characterize social welfare as increasingly privatized and reliant on individuals and companies rather than the government. Fixer Upper and Chip and Joanna Gaines certainly promote and extol the neoliberal fantasy of the self-reliant, self-disciplined citizen. But the wild success and fandom surrounding Fixer Upper is due in part to the affective, narrative, and material differences with which Jo and Chip wield their distinct brand of “compassionate conservativism” to take government down to its studs. As I put in the article, in reality TV defined by individual transformation, the self becomes sovereign; in reality TV defined by renovation, the self becomes settled.

Emplacement—what cultural studies scholars describe as the process through which a thing is firmly established in a particular place—is meaningful here. The Gaines root their brand and their idea of home in the specific materials and place of central Texas, providing viewers with a renovated manifest destiny. As Indigenous scholars have long argued, the United States was and continues to be a settler colonial society, one that claims political legitimacy and territorial possession by denying and dispossessing Native American sovereignties in the past, present, and future. Settler society established and maintains itself by pillaging Indigenous terms, paths, tools, and stories to emplace whites as owners and stewards of the land and its history.

Like so many places in the US, the name “Waco” comes from the Native Americans who were driven from the land by Texas Rangers and broken treaties with the Texas and US governments. A Christian understanding of salvation structures the perception of space and land in this country — justifying and aestheticizing the violence of conquest and theft beneath a banner of improvement and redemption.

The idea and imagery of openness helps facilitate this work. The wide horizons of Texas and the open concept floor plan appear, in the aesthetics of settler society, unmediated and democratic—open to all who have “the guts to take on a fixer upper.” I want to better understand the work, aesthetics, and materials of exposure, mediation, and surface and what they tell us about the desire/demand for Americans to fix up, renovate, settle, and save.

I would really like to quote everything that you wrote about shiplap. Truly, all of it. In lieu of that….can you write us a mini shiplap dissertation?

In HGTV’s Fixer Upper — and, I suggest, in the design cultures it has inspired — shiplap is the ultimate indicator of a history worth preserving. Southern Living magazine calls shiplap a “timeless look,” but architectural features that elicit the nostalgic moniker “timeless” tend to be those that are full of time, laden with violent histories and, as Christina Sharpe says, “the past that is not past, a past that is with us still.”

Shiplap isn’t a neutral material. It carries with it a very specific maritime commercial past, namely the history of capitalism’s birth in the wake of the slave ship. A globalizing, Christian Europe built these ships—with names like The Good Jesus, Hope, Liberal, Friendship, Welcome, and Good Intent—to “save” the people and places of the Americas and Africa by converting them into cargo and parcels organized along a newly imagined racial-spatial axis, in which whiteness was closer to godliness. Sharpe’s investigation of “the wake,” the conditions of Black life in the wake of the Trans*Atlantic slave trade and the global climate of anti-Blackness, powerfully foregrounds the histories, stories, and modern conditions that “timeless” architecture is meant to elide, soften and overcome. Sharpe, Édouard Glissant, Hortense Spillers, Katherine McKittrick and other scholars of Black life and geography allow us to see the ship within the shiplap.

Slavery was a driving force behind the Texas Revolution and the annexation of Texas into the United States, and the Mexican government’s law against slavery angered the Anglos moving into Texas with enslaved people. Often, these migrants ignored the laws of their new home, and the tensions and conflicts that ensued as a result of the then illegal practice of slavery helped catalyze the Texian revolt against Mexico. After nine years of nationhood, Texas was annexed into the United States in 1845 as the result of attempts by Presidents Tyler and Polk to gain political advantage by increasing the number of slave states.

This was not the history I was taught in my seventh grade Texas history class, but it is crucial to understanding the organization and aesthetics of Texas space. Cotton, the predominant material of US slavery, was one of Waco’s primary industries. According to local historian Lavonia Barnes, the Earle-Harrison House—the location of Joanna and Chip’s wedding — bears traces of the enslaved workers who built it: “The hand-molded bricks, some showing finger prints, others chicken and pig tracks, were undoubtedly made on the premises by Dr. Earle’s slaves whom he brought with him from Mississippi.”

The plantation aesthetic is, precisely, a shiplap aesthetic: one that, like the bricks of the Earle-Harrison House, incorporates the physicality of enslavement into the walls of home.

The Gaines’ repeated use of shiplap brings the imagery and materiality of the ship within the space of the home. Shiplap’s plantation aesthetic illustrates McKittrick’s assertion that plantation logic “emerges in the present both ideologically and materially” as a “persistent but ugly blueprint of our present spatial organization that holds in it a new future.” The haunted materials of our history are refurbished into an updated aesthetic and providential orthodoxy with a newly scripted story to tell. In their repeated, ecstatic use of shiplap, the Gaines promise salvation from the horrors of the past and present by way of “timeless” domestic space.

Have you been watching the expansion of the Magnolia Empire (which, well, that word says a lot, doesn’t it) across Waco? I just saw that they bought the building that housed the newspaper to serve as their new HQ, and they’re constantly buying up new properties.

The Gaines have been so successful, in part, because they understand and harness the importance of materials and place. Where Baylor, in classic mid-twentieth century urban renewal fashion, expanded through the demolition of neighborhoods that the town’s Anglo powers deemed to be “blighted” and “slums,” Magnolia has a different relationship to improvement, one which, as you note in your article, is heavily inflected by evangelical Protestant Christianity. By buying up these properties—the silos, the Elite Café, the Grand Karem Shrine building, the Waco Tribune-Herald building, and (many) more—the Gaines are continuing the process through which space is claimed through material historicism.

Following the Mexican-American War (1846-1848), Protestant Anglo settlers used the materials of the region’s Catholic adobe missions to represent themselves as the natural heirs and god-ordained guardians of the once great Spanish empire. They thereby claimed physical and spiritual ownership of the land and worked to displace and discount the Californian Mexicans and Native Americans already on the land.

Today, Magnolia is laying claim to the spaces and structures of Waco’s past for similar effect. Property and spatial control are predicated on ideas of improvement and authenticity. By buying and remodeling these historic sites, the Gaines are positioning themselves as the city’s saviors—stimulating the local economy while preserving its history. Their right to own and control the land is thus bolstered and justified by the apparent benevolence of their intentions and authenticity of their materials. The Gaines are incredibly savvy architects of their empire, though, as the word “empire” implies, Magnolia is far from the first to wield the twin rods of history and improvement.

I have been very interested to watch the ways that the Gaines have successfully sublimated their engagement with Antioch, their church — it’s somehow everywhere and nowhere. It reminds me of being at The Silos for their big opening Spring festival, and always feeling like I almost recognized the music blaring from the speakers, but not quite. It was Christian praise music, but the sort that never says “Jesus” and kinda sounds like Mumford and Sons or Brandi Carlile? It’s this very interesting negotiation of faith and ‘the secular’ that feels purposeful and in line with, say, the Baylor Influencer Twins. Do you know what I’m talking about? What’s happening here???

Oof yes, I see/hear you here, and I have really enjoyed your writing about the B&B twins. I’ll non-answer this question with a number of questions of my own, but I think the husband-wife band Johnnyswim, whose song “Home” is the theme song for Fixer Upper and who have a six-episode series up now on the new Magnolia channel, might help answer and complicate some of what is happening here. This couple—Amanda Sudano and Abner Ramirez—showed up in a few episodes of Fixer Upper and headline, I think, at every Silobration.

They are Christian and first met in a church in Nashville but do not want to be labeled as Christian music. She is the daughter of Donna Summers; he is the son of Cuban immigrants, and the first episode of their show, Home on the Road, provides a rosy “only in America” retelling of the American dream for those who value family, procreate, and work hard. Although, in a 2018 interview in the Christian magazine Sojourners, they critiqued the explicit and implicit racism of white Christianity and the American bootstraps narrative.

What I’ve seen so far of Johnnyswim’s TV show reminds me a bit of the “I’m a Mormon” videos featuring musicians, especially the one with Brandon Flowers, the lead singer of the Killers. These videos might be a generative site of comparison with what the B&B twins are up to—how/why do religions market themselves as cool or cute? Is some of the virulent palatability that the Gaines are working towards a result of the Branch Davidian massacre and the need to distance their faith and their city from anything that feels remotely fringe or fanatical? Also, how significant or insignificant are denominational and doctrinal distinctions here? Does it make sense to conflate or equate the conservativism of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (B&B twins) with the conservatism of Southern Baptists (Baylor) with the conservatism of non-denominational Christianity (Antioch), or is it important to understand what separates them and why?

I tend to think these distinctions matter, but looking at conservative Christianity from a musical perspective, as your question does, might illuminate overlaps and fault lines that differ from the words on church buildings and the assertions of church leaders.

What are you working on now — and/or what can you not stop thinking about, even if it’s outside of your academic study?

I’m starting to work on my dissertation, in which I grapple with the conjunction of material and religious history in Texas, the US-Mexico Border, and the US Southwest. In particular, I keep returning to the materials and textures of these places: cement and adobe in the art and houses of Marfa, Texas, limestone in San Antonio’s aquifer and Alamo, shiplap in Waco, tires in Taos Earthships, etc.

I’m also putting the finishing touches on a paper about a building in New Haven, and I have a side dream of writing an article about Fate of the Furious (the latest Fast and the Furious) movie as a theological dialogue between Vin Diesel’s character and Charlize Theron’s character, but that will probably have to wait. I’ve also finally started outlining and doing research for the queer romance novel I’ve had clunking around in my head for years now. Genre novels—romance, mystery, fantasy—have been a big part of how I’ve survived grad school thus far and the past year.

I see myself working at the intersection of American religion, geography, and architecture. People will likely think first of church edifices, but I’m more interested in spatial mapping, materials mining, and design—how all of these activities in the United States have been informed by, and form, religious ideas. My focus is on the US Southwest and US-Mexico Borderlands, and I’m really excited to connect with readers about resources they’d like to share or if there are places they think I should pay attention to—especially related to adobe, cement, or limestone—I’d love to hear about them.

If people want to read more about these ideas, can you recommend some places to start?

Brodesser-Akner, Taffy. “Are You Ready to Meet Your Fixer Uppers?” Texas Monthly, Oct. 2016.

Parker, Ian. “HGTV is Getting a Renovation.” The New Yorker, March 29, 2021.

Barnd, Natchee Blu. Native Space Geographic Strategies to Unsettle Settler Colonialism. Oregon State University Press, 2017.

Barraclough, Laura R. Making the San Fernando Valley: Rural Landscapes, Urban Development, and White Privilege. University of Georgia Press, 2011.

Bhandar, Brenna. Colonial Lives of Property: Law, Land, and Racial Regimes of Ownership. Duke University Press, 2018

Cheng, Anne Anlin. Second Skin: Josephine Baker and the Modern Surface. Oxford University Press, 2011.

Jennings, Willie James. The Christian Imagination: Theology and the Origins of Race. Yale University Press, 2010.

King, Tiffany Lethabo. The Black Shoals: Offshore Formations of Black and Native Studies. Duke University Press, 2019.

Lint Sagarena, Roberto Ramon. Aztlán and Arcadia: Religion, Ethnicity, and the Creation of Place. New York University Press, 2014.

Lofton, Kathryn. Consuming Religion. University of Chicago Press, 2017.

Nichols, Robert. Theft is Property!: Dispossession and Critical Theory. Duke University Press, 2020

Sharpe, Christina Elizabeth. In the Wake: On Blackness and Being. Duke University Press, 2016.

If you have comments or questions for Rebecca, please leave them below!

If you read this newsletter and value it, consider going to the paid version. One of the perks = weirdly fun/interesting/generative discussion threads, just for subscribers, every week. We have a very good reader-generated question for this coming Friday Thread. The other perk: Sidechannel. Read more about it here.

If you are a contingent worker or un- or under-employed, just email and I’ll give you a free subscription, no questions asked. If you’d like to underwrite one of those subscriptions, you can donate one here.

If you’re reading this in your inbox, you can find a shareable version online here. You can follow me on Twitter here, and Instagram here. Feel free to comment below — and you can always reach me at annehelenpetersen@gmail.com.

Sort of an aside, but not really, I went diving into the Duggars' Instagram friends (attempting to find a finstagram), and noticed that they followed other Duggars and the Gaines's almost exclusively.

I can't put my finger on what it is, exactly, about Chip and Joanna Gaines that causes the part of me that rejects my fundamentalist upbringing to be thoroughly disgusted by them. When I was in high school I worked at Mardel Christian Bookstore in the music section. On the walls we had a poster that said things like "If you like the Goo Goo Dolls, then try SonicFlood" and "If you like Destiny's Child, try Mary Mary." Maybe their show is like that poster, except instead of promoting a (mostly) harmless Christian band, it promotes Evangelical dominionism behind a saccharine, bleached smile.

Maybe the Duggars and the Gaines are just two prongs of the same fork.

This was fantastic. Thank you for sharing this kind of thinking and writing! Would be so interested to see a similar analysis of empire builder Ree Drummond/ Pioneer Woman and the American West. I’m also pretty fascinated by the power trio of design influencers/related Mormons Gabrielle Blair, Jordan Ferney & Liz Stanley.