Welcome to Part Two of Bama Confidential, a week-long series that goes deep into the past and present of Greek Life at the University of Alabama. If you missed Part One — on sorority rush — or just want to read the intro to the series, and how it found its way to Culture Study, you can find it here. If you want to explore the content coming out of #Rushtok this week, I’m curating it over on my Instagram (and make sure and check the pinned stories).

Regular Culture Study Readers: This series will arrive in your inbox every morning this week. If it’s not your thing, don’t worry, we’ll be back to regular Culture Study programming next Sunday. If you’re not a Culture Study subscriber but want to make sure you don’t miss the next installments, just sign-up below.

It was a winter night in 1986, and John Archibald was sitting at a table at Wings & Things on University Boulevard in Tuscaloosa. This night was memorable for two reasons. One: it was the first time John had ever eaten Buffalo wings. And two: he was on a stake out.

John was a self described “bad boy” in the early 1980s. The son of a preacher, he'd flunked a few classes in high school and gotten himself arrested for stealing a box of condoms at the local convenience store. The security guard who caught him was actually one of the ushers at his father’s church, so there was no hiding that one from the old man. After flailing at community college, John decided to go where almost no one goes to get their life on the straight and narrow: the University of Alabama.

It was the early 1980s when John arrived on campus. He quickly found his way into the journalism program and began writing for the student newspaper, The Crimson White. At the time, the newsroom atmosphere was like something out of a movie: people would work until late at night, cigarette smoke hanging in the air and tumblers of whiskey littering the desks. And writing was only part of it: after finishing an article, they’d stay up cutting printed columns with Exacto knives and laying out the paper on a giant table.

“We felt like it was just us against the world,” John told me. And in a way, that was true, since at Bama, the Greek system can feel like the whole world. And that’s exactly who John was against.

Audio: Meet John Archibald, who got his start in journalism writing for the student newspaper, The Crimson White, back in the 80s.

On campus, John was a GDI: a “God Damn Independent.” As in: not Greek. It’s a label he wore proudly, just like the people I knew at my own college who semi-jokingly referred to themselves with the same moniker. Which is why it was a bit surprising that John was sitting in Wings & Things across from Alecia Sherard, a Phi Mu who absolutely loved being in a sorority. She loved the rituals, the songs, the parties, all of it. But she was also a journalism major, and had quickly become a star reporter at the Crimson White, with a particular interest in politics. When Barbara Bush (then Second Lady to VP George H.W. Bush) was honored at Bama with a tea party, Alecia walked right past the Secret Service and asked for an interview.

Meet Alecia Sherard, another UA alum who also wrote for The Crimson White in the ‘80s.

But that night, John and Alecia were at Wings & Things, noses pressed to the glass, on a mission. They’d been staring at the Sigma Alpha Epsilon (SAE) fraternity house across the road for well over an hour, because John had been tipped off that a meeting of “The Machine” was taking place inside. John was determined to figure out who was at that meeting — and the names of that year’s representatives from each Machine-affiliated house. It was something only a select few people inside of Greek Life were ever told, and that information rarely — if ever — made it to outsiders.

John had somehow got his hands on a list of Machine representatives, but they wanted, in Alecia’s words “at least double confirmation on every one of ‘em.” Finally, they saw people leaving the SAE house. This was their big chance — if they could just identify each of these students, they’d be able to print their names. The whole campus would know who was behind the curtain, pulling the strings on campus politics. They knew it wouldn’t necessarily bring down The Machine, but it would at least bring it out into the open.

John was ticking off the names on the list, matching them with the people he saw leaving the SAE house. But he knew that if he wanted a really good story, he needed to actually confront one of them. So he stepped outside and walked towards the house.

John wasn’t expecting a warm welcome. But he also wasn’t expecting all hell to break loose.

As soon as they saw him, the Machine members began shouting to each other to run, quick, and hide. John and Alecia both recall the mayhem as people sprinted for their cars, bags and coats and t-shirts pulled over their heads in a feeble attempt to obscure their identities. Tires squealed as car after car shot off into the darkness, as if they were the police raiding an underage party, not two novice reporters trying to ask some questions.

At that point, most people might call it a night. They’d gotten enough names to write their story. But John and Alecia took off in pursuit. “We went out and we tried to follow them,” John told me. Alecia said she felt the adrenaline pumping through her, as if she was Robert Redford in the Watergate movie All the President’s Men. John and Alecia were hot on the trail. And that’s when the cars they were chasing stopped and turned around. And started driving towards them, headlights staring them down, getting larger.

John and Alecia turned off the road, hoping this was just some quick effort to scare them off. Nope. Trucks full of fraternity boys were chasing them down the streets, around every corner, until finally they made it to relative safety: UA’s Student Center, which then housed the Crimson White office.

John and Alecia ran inside, but even then, the trucks didn’t back down. “They were just driving around the building. All night,” Alecia recalled.

The pair started writing their exposé immediately. They were used to working late. But they weren’t used to doing so with the sound of honking horns and revving engines and tire burnouts happening outside the window.

They kept peeking out the window, worried that the Machine kids were going to get out of their cars and storm the building. It never got to that point. They pulled an all nighter, ensuring the story would be in the next morning's paper. And by the time they left, the cars outside were gone.

They did it. They got their Machine exposé.

When John finally went to sleep, he did so certain things on campus would be different when he woke up. The university’s controversial secret organization had been dragged out of the shadows!!! Everyone would be talking about it.

But instead, when John woke up, it was like no one had read the piece.

Because they hadn’t.

Remember: this was 1986. If you wanted to read a piece in the Crimson White, you had to have a physical copy of the Crimson White. Which hardly anyone had, because the Machine had sent out people to steal and destroy every physical copy on campus. John and Alecia raced around the distribution locations and found rack after rack of Crimson White stands sitting there completely empty.

All that effort, for nothing. The Machine had won. “They were more organized than we were,” John told me. “Which is always the true battle of journalism versus corruption.”

When I started working on a story about Greek Life, I did not think I'd end up recounting a 1980s stakeout and car chase. But then again, I had no idea about the Machine. And neither do most people in this country. Even some students on UA campus don’t know that it’s anything more than a rumor. But for almost a century, this elite group has been at the center of Greek Life at the University of Alabama.

(I should note that it's basically impossible to reach out to a secret society for comment. The Machine doesn't have an email address, a phone number, a website, a post office box, or anything else a typical organization does, so here and throughout the series we're going off what we heard directly from our sources, or what's been reported in the media before. But hey, if a representative from the Machine would like to sit for a proper interview, get in touch! We also reached out to the University for comment about the Machine, but they did not answer our questions; we reached out to 11 sororities and fraternities concerning different components of this story, and Phi Mu was the only one to respond — and they just asked us to reach out to nationals, which we did, and still haven't heard back.)

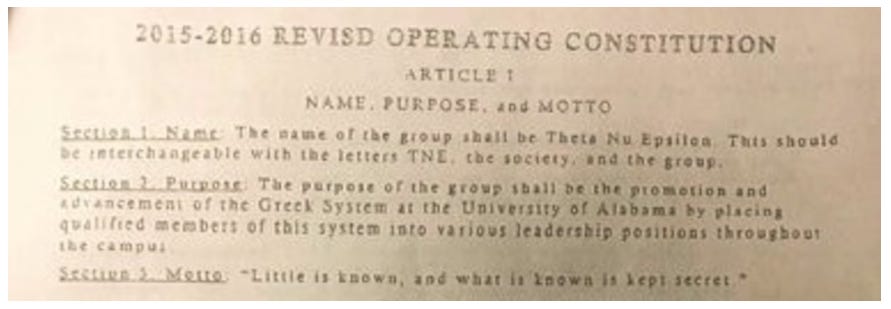

Secrecy is written into the DNA of the Machine. A couple years ago, an anonymous source emailed members of the media as well as the UA administration a copy of a document that purported to be the Machine's constitution. It was never verified because of, well, secrecy, but the document notes that the Machine’s motto was: "Little is known and what is known is kept secret."

Most students I interviewed mentioned the Machine only in hushed voices. Some mentioned things off the record, but most refused outright to even talk about it for fear of retaliation. Even faculty didn’t want to talk about it — who knows what sway former Machine members hold over tenure approval?

The Machine, which has helped usher students into positions of power on campus, has even done so for the Alabama state house and the federal government. One of Alabama's current US senators, Katie Britt — who delivered the GOP rebuttal to the State of the Union earlier this year — got her start as the (“allegedly” Machine-backed) candidate for UA student body president. For more than a decade, her portrait hung in Bama’s student government building, a reminder of what the system could do for you if you worked it correctly — and what you might be up against if you try to take it on.

But does The Machine still matter? Or does most of its power stem from its reputation? If it’s a benign political organization, why keep its working secret? And why does the university itself look the other way?

●

The Machine started at the University of Alabama a century ago — some date its inception to 1914, others as far back as 1888. Its real name is Theta Nu Epsilon, and it operates as a kind of meta-fraternity: an alliance, basically, that acts on the behalf of Greek Life. Every year, The Machine picks candidates from Greek organizations to run for everything from SGA President to student senators; it then supports their campaigns by allegedly pressuring fraternity and sorority members to vote for that candidate. Think Tammany Hall, only instead of controlling the election for New York City mayor, they’re compelling fraternity brothers to get out there and vote for the Machine candidate for homecoming queen.

Many Greek students say they’ve been given written instructions on who to vote for, and asked to show proof of voting. Some say they were fined by their Greek organization if they did not vote. And when the Machine candidate wins, which they do almost every time, they ensure that Greek Life's interests are furthered on campus.

All of which makes it sound kind of dull — a voting bloc, basically. Which it is. But as has been reported many times over the years, the Machine seems willing to go to great — and even violent — lengths far beyond the voting booth to secure and maintain power for the Greek system and its elite houses.

We were unable to find any situations in which the university has officially acknowledged that the Machine exists, and several people told us that it had never happened. Until the administration does so — and there’s no reason to assume it’s going to start acknowledging it now, after almost a century — it’s hardly in a position to stop it. It’s left up to students, like John and Alecia.

John tells me about when he first started to understand the Machine as a “select group” of sororities and fraternities, and why he still cares about it all today, decades after he’s graduated from UA.

Over its 100+ year history, the Machine has gone through periods of visibility and relative quiet — basically it gets bold and public and a bunch of bad press and recedes from view for a decade or so before reappearing. The 1980s were one of those active periods. “They were quite busy while I was there,” Alecia told me. “And they were really, really thuggish.” Which is saying something, given the Machine’s apparent history of thuggishness up until that point.

For decades, it was made up of only white men. (There were no Black students allowed on Alabama’s campus until 1963, when the school was forced to desegregate. There were white sororities before 1963, but women were not invited to join the Machine — until, as you’ll see below, their votes became necessary.) The Machine’s main purpose was influencing the direction of student politics — and that direction was always, at heart, conservative. As in: conserve the status quo. Which meant conserving patriarchal order — and conserving white supremacy. As John put it to me, “it was built as a racist organization.”

From the time the Student Government Association began in 1914 until John and Alecia got on campus in the early 1980s, all but seven SGA presidents were Machine-picked candidates. But in 1976, a Black student named Cleo Thomas decided to run for SGA president — the first Black student to attempt a run. He won, even without Machine support, because he struck his own alliance with Black students, independents, and white sororities — a sort of counter-Machine voting bloc. For the first time in history, the Machine was a minority.

“It was at that point that the Machine began to see the strategic value of bringing women on board,” John told me. By bringing sororities into the Machine, they could shore up a larger voting bloc and minimize the chances of a Cleo Thomas situation happening again. Which is exactly what happened. The Machine was so against a non-Machine candidate, and a Black non-Machine candidate in particular, that they were willing to let women from white sororities into the organization. And white women were seemingly cool with this plan. (Sidenote, but this is truly a classic move in the history of white ladies).

After Cleo Thomas’ election in 1976, more than two dozen men in white sheets walked out of the Kappa Sigma fraternity house on campus singing racist songs, chanting “We Shall Overcome,” and throwing bottles. University Police reported an eight-foot cross was burned in front of the Kappa Kappa Gamma sorority house (then an all-white sorority) which had supported Thomas’s run (they were allegedly fed up with the Machine’s refusal to allow female candidates to run).

Reporting at the time attributed these actions to individuals who were allegedly in the Machine and “burning off steam,” choosing to target specific groups as retribution for their support of the Thomas campaign. “The Machine is upset,” one campus leader said. A few days later, the UA Inter-Fraternity Council released a statement condemning the events, but there didn’t appear to be any further response from the administration.

The Machine faltered again, just a few years later in 1983, when another independent candidate managed to win the vote for SGA president. After the election, that president — a man named John Bolus — discovered his house had been wiretapped. Local law enforcement called in the FBI to investigate. It was like Watergate… but on a college campus. In the end, two students — both members of Machine fraternities — were arrested and confessed to authorities. But since the case didn’t rise to the level of “criminal conspiracy,” as the FBI put it in a 1983 article in the AP, the whole thing was ultimately chalked up as “a college prank” (although the wiretap was functioning).

It may well have been a prank, but it was a prank designed to intimidate. After a twelve-month good behavior bond, the charges against both students appear to have been dropped.

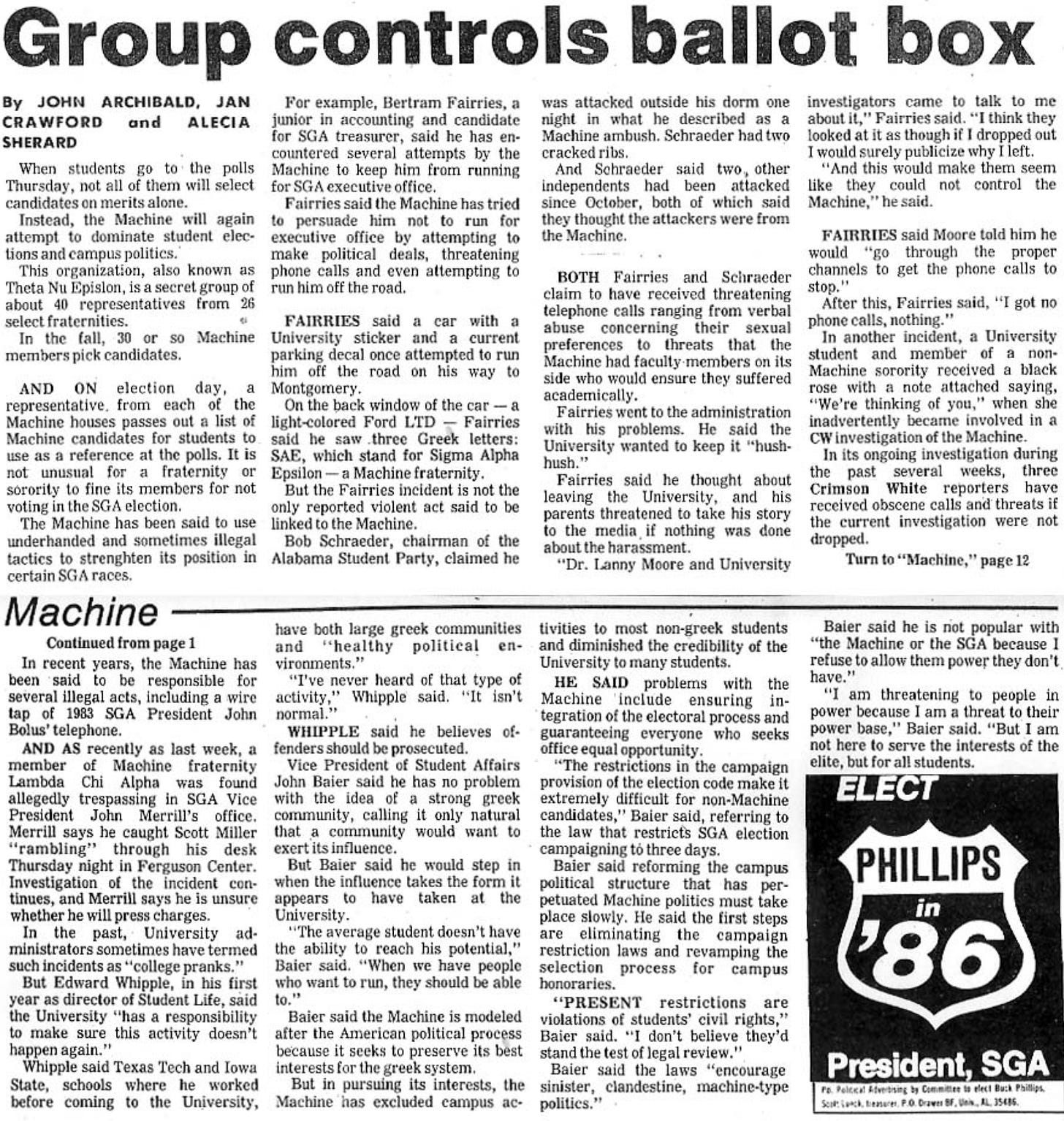

John had arrived on campus the year before, in 1982, and Alecia in 1983. That was all in the air as they got their footing as journalists and decided to report on the Machine. Shortly after alleged Machine members chased them back to the Crimson White office, a Black man named Bertram Fairries ran for SGA treasurer. In an interview with the Crimson White, Fairries said that the Machine tried to persuade him not to run. When he refused to drop out, he was inundated with threatening phone calls. But the harassment didn’t stop there. One afternoon, he was making the two hour drive from his hometown of Montgomery back to campus in Tuscaloosa. Along the way, he was run off the road by a car full of white men. Before the other car drove off, he noticed a UA parking decal on the car — and a bumper sticker with the letters SAE. In a phone call last year, he told us that he felt “tremendous racial overtones” and that the incident left him anxious and scared.

When Fairries got back to campus, he complained to the administration — and sat down with John Archibald for an interview. Fairries said he concluded, based on the University’s inaction, that they wanted to keep the whole driving incident “hush-hush.” That article also included the story of Bob Schraeder, chairman of the Alabama Student Party, who had been attacked outside his dorm by who he claimed were Machine members, and ended up with two cracked ribs. John reported that at least two other independents had been ambushed in previous months; both thought the attackers were from the Machine. Someone had broken into the office of an independent candidate for SGA president. Everyone was convinced that the Machine was behind the attacks and break-ins — but couldn’t prove it.

The violence continued to escalate. In 1986, the first Black sorority, Alpha Kappa Alpha, moved into a house on Sorority Row. “Of course,” Alicia told me, “they burned a cross on sorority row.” Since it’s difficult — impossible, really — to confirm the identities and affiliations of the perpetrators behind this event, we can only speculate that The Machine was behind it. (The Machine did not, of course, publicly comment, because The Machine does not acknowledge its own existence). But Alecia was just one of many students who recall this incident, and her memories speak to the understanding among students on campus at the time, and since then: the Machine is here.

The university administration publicly decried the cross-burning. Edward Whipple, the director of Student Life at the time, told the Crimson White that the university “has a responsibility to make sure this activity doesn’t happen again.” Whipple had previously worked at other schools with large Greek populations, including Texas Tech and Iowa state, and acknowledged these situations at Alabama were outside of what he’d usually encounter. “I’ve never heard of that type of activity,” he said. “It isn’t normal.” But as far as we can tell, the school did not investigate these incidents, or address the open secret that The Machine may have been behind the previous acts of violence and sabotage. And it refused, as it always had, to acknowledge the existence of The Machine at all. In its silence, the university continued to grant the Machine its greatest power: its secrecy.

●

Alecia tells me how on paper she was perfect for her sorority, and then recalls her introduction to the Machine.

Phi Mu didn't like one of its members — Alecia — actively reporting on SGA or the Machine. After all, Phi Mu was a Machine sorority. One of Alecia’s sorority sisters told her that she had wanted to run for Homecoming Queen, but the Machine wouldn’t allow it. All because of Alecia’s reporting.

Girls in the house were mad that Alecia was jeopardizing the reputation of Phi Mu. One day, she was coming down the back staircase of the Sorority house, where she lived at the time, when she noticed something odd. There was a bulletin board with pictures of sorority sisters, including Alecia. “And someone had taken a pencil and carved my face out,” she says.

Alecia doesn’t know who did this, but there was, of course, a Machine rep in her sorority. It seemed like another intimidation tactic. Eventually Alecia was called in for a meeting with a local alum who was involved in the sorority. “I thought she wanted to talk about her daughter. I thought there must be something going on that she wanted to tell me about,” Alecia recalled. But no, there was something more sinister at play. “Stop. Stop, Alecia. Or we're gonna kick you out,” Alecia remembers the alum telling her. She was given a choice: quit working at the paper (and stirring up trouble), or leave the sisterhood behind. Alecia found the entire situation shocking and confusing. What rules was she even breaking? “Bringing harm to the chapter,” is what it really boiled down to, Alecia told me.

So Alecia made her choice. By the end of her junior year, at Alecia’s request, her chapter voted and allowed her to become an inactive alum of Phi Mu. She got to keep her letters, but she moved out of the house.

●

John graduated in 1986, Alecia in 1987, but they kept tabs on the happenings at their alma mater, especially anything related to The Machine. And in that department, there was plenty to keep track of, like the “Bama-bino pizza fiasco,” as Alecia calls it.

You know how on every college campus there’s that one pizza shop that everyone orders from late at night? That’s what Bama-Bino’s was at UA in the late ‘80s. The son of the owner went to UA, and in 1989, decided to run for SGA as an independent candidate. The Machine allegedly retaliated… against the restaurant. Based on later reporting, it appears that the same fraternities and sororities that had supported it for years organized a boycott. By 1991, Bama-Bino’s was out of business. But that’s nothing compared to what was coming.

In 1993, Minda Riley — a Phi Mu, like Alecia — decided she wanted to run for president. She wanted Machine backing, and when they didn’t pick her as their candidate, she decided to go it alone. And the Machine allegedly retaliated. In late January, Minda reported that she was attacked in her home by a man wielding a knife. She escaped with minor injuries — a bruised cheek, a busted lip, a cut on her face — but has refused to talk about the incident in the years since.

Still, the incident represented a serious miscalculation by the culprits. Because Minda wasn’t just any Alabama student. Her father was Alabama congressman Bob Riley — the man who’d later become the state’s governor. Then-President of UA, Roger Sayers, seems to have decided that something finally had to be done. According to reports from the time, the UA President met with Minda and her supporters. And while we don’t know exactly what happened in that meeting, we do know that afterwards, all of the student government was shut down for three years.

Instead of going after the Machine or implementing any policies to meaningfully alter its behavior or reduce its influence, UA went the route of “reform of student government.” Given the high turnover of college campuses, perhaps the school thought this would be time enough to give things a hard reset. But the Machine has survived for generations, passing down its values and practices from one cohort to the next. It’s far too cemented in Bama life to disappear so easily. Which seems obvious even to an outside observer. So perhaps the goal was something else: to take a public stand without actually supporting lasting change.

There is, after all, a vested interest in maintaining the status quo of Greek Life at Alabama, because Greek Life is one of the main things that attracts students from around the country to its campus. Coupled with the university’s reliance on external fundraising for all sorts of projects ($220 million in 2022 alone), much of which comes from alumni who were members of Greek Life. (Two married alumni, both of whom were members of Greek organizations, are currently matching donations up to $25 million). The assessment seems to have been made: we’d rather tolerate the Machine than risk those donations.

●

Memories of college linger for John and then Alecia, too — in part because, like the end of a good screwball comedy, they got married soon after graduating. They’re still married to this day, and when I interviewed them, they finished each other’s sentences. John moved to Birmingham and started working for the Birmingham News, while Alecia found her role in the business side of the paper. John’s a two-time Pulitzer Prize winner, and yet for all the investigations he’s conducted over the years, he’s still vexed by his efforts to expose the Machine. “The big frustration of it is that they're really good at secrecy,” he told me. “Even people who have been in it and regret it and think it's terrible are reluctant to talk about it.”

Although they left UA decades ago, they still see The Machine everywhere. “The reason I still care about it at the age of 60 is because it's had such an outsized effect on politics in the state beyond,” John explained. This isn’t ancient history, and it isn’t just students play-acting a secret society. The tentacles of Machine influence appear to reach far beyond campus — even into the US Senate.

John tells me about how the Machine shaped him as a writer and two-time Pulitzer winning reporter.

In other words: the story of the Machine is far from over. When student government resumed in 1996, after the three-year ban, so too did the secret society that sought to control it. (In fact, there’s no evidence or reason to assume it disbanded in the interim.) It wouldn’t be long before other scandals could seemingly be traced back to its members. But the university continues to refuse to acknowledge its existence.

There is, however, one intervention the university made into Greek Life. One that doesn’t directly touch on the Machine but does go right to the heart of its founding, and that brought the University of Alabama, briefly, into the spotlight of national media. Honestly, I still can’t believe it took until 2013 for it to happen — and tomorrow, you’ll see why. ●

Click here to keep reading.

Further Reading:

This is incredible reporting about a bonkers situation but honestly my biggest takeaway is that I need a TV show about Alecia and John and their time at the Crimson White! This story has everything!

As someone who has lived in Alabama most of my life, I'm fascinated, disturbed, and not as surprised as I wish I was.

This is a great series! It's an interesting subject even if none of it's relevant to your life. It's been a lot to think for about for me as someone who grew up around Alabama old money without being rich myself and having no idea what the social norms were yet knowing I wasn't doing it right. And also helps explain a little of my dismal experiences volunteering with political and advocacy groups in this state. There's such a deep sense of fatalism.