Last August, I wrote a piece about Bama Rush and the current fascination with Greek Life, fueled by TikTok and a subgenre of videos known as #Rushtok. In that piece, I hinted that I was working on something much larger about Greek Life at the University of Alabama, which was initially a podcast made with a team of producers and researchers. We spoke to dozens of past and present participants in and around the UA Greek System, and it’s finally settled into this form: a five-part series, all published here on Culture Study, with bonus audio for those who want to go really deep.

This week, Rush is in full swing at Alabama. Over on Instagram, I’m curating a seemingly endless stream of Rushtoks — but here, we’ll be diving into the past and present of the UA Greek System, from the performance of Southern femininity to the secret society that serves as a political training ground (and has quietly and not-so-quietly worked to control the campus status quo for decades).

If you weren’t part of Greek Life, some of this is going to seem like stories from a different planet. If you were, some of this will be very “oh well yes, of *course* we all had to present ourselves to a committee of older women who told us whether our shorts were too short!” But some of it will still surprise you, or make you think more about how practices that are pretty objectively fucked up become normalized through repetition and the narrative of history. There’s something for everyone!

Finally, if you get to the end of this article and wonder why I didn’t talk about [insert specific aspect of Bama Rush here] — be patient, we’ll get there.

Regular Culture Study Readers: This series will arrive in your inbox every morning this week. If it’s not your thing, don’t worry, we’ll be back to regular Culture Study programming next Sunday. If you’re not a Culture Study subscriber but want to make sure you don’t miss the next installments, just sign-up below.

With a population just shy of 100,000, Tuscaloosa looks a lot like most mid-size cities in the U.S. There’s big box stores, and a downtown that’s slowly coming back to life, and that one new restaurant where all the millennials go to with cement floors and loud metal stools and IPAs on tap. But then you drive up University Boulevard, and slowly the hulking stadium comes into view, and the streets fill with crimson banners, and oh, wait, there’s a giant mansion, and another one, and another one, and you realize: this is a company town. Only instead of a steel manufacturer or shoe factory employing seemingly half the town and directly affecting the lives of all the rest, the company is The University of Alabama.

UA — or “Bama,” depending on who’s doing the talking and who they’re talking to — was established in 1831 and is currently home to over 39,000 students and at least 7,400 employees. But whether or not you attend or work at the university, if you live in Tuscaloosa (and even Alabama more generally), Bama functions as a secondary (and not always secular) religious institution. You attend services (games); you wear the appropriate garments (infinite arrays of crimson and white); you venerate the saints (former football head coach Nick Saban, first and foremost).

There are town-swallowing, addictive, and quasi-religious college football fandoms all over the country — but none quite like Alabama. And while everyone is ostensibly welcome in this larger church of Alabama, to really belong, you need to figure out how to best match the people sitting in the front pews, in everything from accent and hairstyle to politics and lifestyle. They’re the ones with the power. And the most direct line to becoming part of that club is deceptively straightforward: you join the Greek System.

The University of Alabama has the biggest Greek System in the country. Those giant mansions I mentioned earlier? Those are the sorority and fraternity houses, and they look more like someone built a normal-sized mansion, then decided “okay but what about MORE MANSION?” and then built a second one, affixed to the back. Mansions on mansions on mansions.

The mansions are uniform brick with soaring Greek columns, wrap-around porches, tasteful white-washed rocking chairs — and interiors that look like they were decorated by someone’s very rich grandma, because they were. The style of the sorority women’s hair and makeup change, but the decoration does not. Think thick carpets, grand pianos that no one plays, massive staircases out of Gone with the Wind, and couches upholstered in the sorority’s colors, even if those colors are bronze, pink, and blue. They’re meant to signify timeless class, taste, and feminine refinement to anyone who steps in the front door — from prospective new members (PNMs) to parents.

You know which houses are the “big” houses because of their place of prominence (and proximity to the football stadium). The houses are built with money from the Greek organizations and maintained through a mix of dues (which, at Bama, can run up to $5,000 a year) and alumni donations. And even though these houses look old, some are deceptively young — and are frequently renovated. (The renovations that began on the ADPi house earlier this year are running upwards of $2 million; Alpha Chi got a brand new $12 million house in 2014, which alumni donors funded via a 30-year loan; we reached out to both UA chapters to confirm these numbers, but have yet to hear back).

Audio: Emie Garrett, one of the UA students I interviewed, gives me a little tour around campus and sorority row.

At the small liberal arts school where I rushed, living in the sorority section of our sophomore dorm was the same price as anywhere else on campus; at Bama, sorority and fraternity housing costs significantly more — and you can’t use your financial aid to cover the costs. You either have family that can cover it or you take out private loans. And while lots of people who attend the University of Alabama don’t come from money, most people in the Greek System do — some from regular upper middle-class money, some come from “American Gentry”-style small town families (think: Dad owns the biggest car dealer) and some come from the Chicago suburbs, Orange County, and New Jersey. One day on Greek Row I counted at least eight Jeep Wranglers just from where I was standing. One student told me the real car of choice amongst the Zetas is the Mercedes Benz G Wagon, which run upwards of $140,000. Driving those cars doesn’t necessarily mean you’re filthy rich, but it does mean you want to convey a certain level of wealth.

If you’re a rich girl from Jersey who wants to become a Zeta, in other words, you know which car to bring if you want to fit in. But there are over 60 Greek organizations at Alabama. How does everyone else figure where they want to end up? Well, that’s what Rush is for.

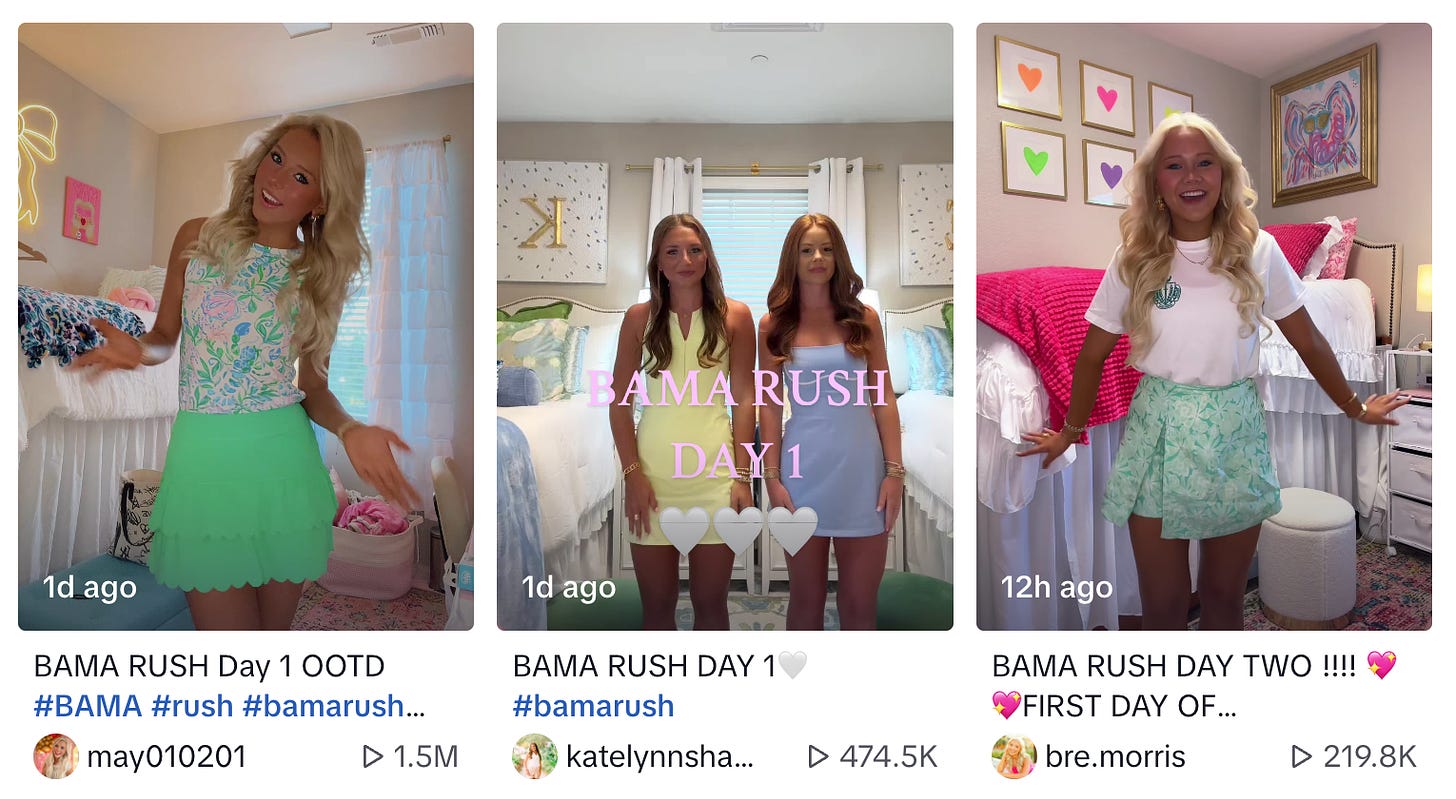

Even if you weren’t a part of Greek Life at college, you might still know a little something about Rush — especially if you were somehow drawn into #Rushtok, the umbrella term for the tens of thousands of short Rush-related videos that first proliferated on TikTok in the summer of 2021, largely but not exclusively focused on the University of Alabama.

But when it comes to Greek Life, #Rushtok is like the shiny exterior layer of the jawbreaker. There’s so much more to unpack and explore — through analysis, sure, but also by, well, actually talking to people who’ve been through it. So if you were part of Greek Life somewhere else and you think you already know this stuff — you absolutely don’t. And if you watched hours of BamaRushTok videos and think you know — you don’t. That’s just the part they want you to see. They allow you to see. And that, remember, is just the first week of semester.

●

The term “Rush” comes from the early days of Greek Life in the late 19th and early 20th century, when sororities and fraternities used to literally "rush" to the train station to meet new students and pitch them on joining their organization. These days, most college students don't show up to campus by train, but other values of that early Rush era remain. Sororities and fraternities have images to maintain, and every year they need to attract new students — the “right” kind of students — to perpetuate it. That emphasis on fitting in (which, at Bama, generally means being white, attractive, wealthy, and straight) has been there from the start, and is why, despite considerable cultural and demographic changes to our country, Greek Life at historically white institutions in many ways still looks a lot like it did a hundred years ago.

The one big difference: way more students are coming to Alabama from out of state, many with the explicit intent of joining the Greek System. Twenty years ago, students from outside of Alabama made up less than 20 percent of undergrads. Today, they make up nearly two thirds of the school. (You can read more on what’s driving upper-middle-class white kids to schools like UA here).

“It’s literally like Disneyland for college kids, I swear,” Kylan Darnell told me. Kylan was a breakout star of #Rushtok in 2022, in part because she arrived on campus (and to #Rushtok) with hundreds of thousands of followers and hours of media training in tow. Kylan grew up in a small town in southern Ohio and started doing beauty pageants when she was seven years old. Her mom had been a beauty queen, her younger sister competed in pageants, and Kylan was crowned Miss Ohio Teen in 2022.

Here’s a bit of my interview with Kylan — it’ll give you a taste of her Ohio farm girl meets Bama sorority girl accent.

The best way to describe Kylan’s appearance is that she looks like a doll. Big brown eyes, perfectly highlighted hair, fake eyelashes, uniform spray tan always tastefully applied. That might sound like pageant glam, which it is, but it’s increasingly just everyday glam for a certain type of woman between the ages of 16 and 26. (If you’ve watched any of the “Get Ready With Me” Videos for people doing #Rushtok, you know exactly how formidable their makeup skills have become. I didn’t even know this many types of foundation existed).

Kylan came to Bama for the same reason so many beauty queens do: because they match pageant scholarship dollars, and over her decade plus of competing in pageants, Kylan had amassed a sizable fund. Alabama is one of the only major universities that offers this match, but it’s honestly a brilliant recruiting strategy. How do you get more traditionally beautiful, academically invested, proficient public speakers to come to your school? Recruit them where (many) of them gather: on the pageant circuit.

When I met Kylan, she was glammed up in a black velvet bustier for an appearance later that day at a dance-a-thon in Birmingham. In person, she’s a lot taller than you might assume, and walked down the halls of her dorm, where absolutely no one was wearing anything even approximating a black velvet bustier, with assurance. To an outsider, Kylan looks like someone who’d easily get a bid to every house on campus. But anyone fluent in the Greek system knows that the criteria can be very opaque and very narrow. She might have looked the part, but I also knew that there were houses that looked at Kylan’s Ohio address and her TikTok popularity and thought: not one of us.

Put differently: it doesn’t matter if you’re a beauty queen if you’re not following the top sorority’s inscrutable rules for acceptance.

●

Like so many processes that determine social order, there are written and unwritten rules — and various means that people pass down the knowledge that make it easier to abide by both. The most obvious is a handy guide published by the university every year called “Greek Chic,” which walks girls through the intricate Rush process. The Table of Contents spans everything from “Summer Dos and Don’ts” to a day-by-day breakdown of how Rush unfolds.

On a very basic level: Alabama’s sorority Rush is broken into multiple rounds over nine (very long) days. At the end of each day, students rank the sororities they’ve seen, and the sororities rank the students. The next day, you spend time at the houses you picked that also picked you. The process is repeated after each round, getting more and more exclusive, with fewer and fewer people invited back. Once you’re out — meaning, you have no matches — you’re out, with no recourse and no do-overs. As a result, each of these nine days — and each interaction with each sorority girl at each of these houses — is crucial. Until finally, at the end of it all, if you’ve made it that far, you find out which (if any) sorority has offered you a “bid” to join.

Most girls find the entire process absolutely exhausting, especially since most have woken up early to spend hours curling their hair. You trudge through the Alabama heat, going to party after party, answering the same questions about your background, your hobbies, why you chose Alabama, etc., even though the active sorority members (also known as “actives” because of their status as a current, initiated member) already know the answers from having read your resume and letters of recommendation. Everyone goes through the motions — and your ability to not seem bored or annoyed or flag in energy is part of the performance on which you’re judged.

And if that doesn’t sound like enough effort, the work actually starts months before, back when you sign up for Rush – usually in May. Just signing up puts you on the sororities’ radar, and the Googling starts immediately. Girls from Alabama (specifically: girls who’ve been gearing up for this day for years — and have sisters and relatives and family friends who’ve been in sororities and implicitly and explicitly tutored them in the process) know that by this point (if not before!) all your social media profiles should be totally scrubbed of anything even resembling “bad” behavior.

No visible drunkenness, no red solo cups, no cigarettes, no super revealing outfits, no thirst traps, maybe not even any bikinis, depending on the sorority you’re looking for. Oh, and probably no political content — although a little Jesus never hurt. One woman told me that she’d be advised to scrub her Venmo. (And if you think that you can just set your profile to private, wrong again: active members will start friend requesting you… and screenshots of locked accounts circulate freely.)

Then there's the Rush application video. Talking to the girls about these videos — well, the whole process is an exercise in agony. You introduce yourself and answer a few basic questions so the sororities can get to know you, but what they’re really getting to know is the skill with which you do your makeup, your ease on camera, and what sort of house you live in. Obviously none of that is explicitly part of the process, but those signifiers are all there for anyone watching to read.

Most sororities also require you to submit (sometimes dozens) of recommendation letters. The written rules say that they can come from “anyone” (a guidance counselor, a youth group leader), but those with “legacy” connections know that’s absolutely not the case — at least if you want to have a chance at the more selective sororities. For them, you need letters from women who were in sororities: preferably at the University of Alabama, and preferably were also members of that sorority.

In practice, that means that a whole bunch of prospective new members have “recommendations” written by the friend of a friend who works with their dad. They’re not recommendations so much as evidence of social capital: that your parents are connected to people who were in Greek organizations, which is to say, that they occupy a certain place within the social hierarchy.

If you grew up in a swanky suburb of Birmingham, you’ve known this stuff for years. You might have attended an informal prep class hosted by alumni in your community, or the class might have been held at your private school (absolutely a thing, as weird as it sounds). And if you didn’t grow up in one of those places, and realize that you have absolutely no idea how to play this game with all these unwritten rules, but you really, really still want to….well, then you hire a Rush consultant.

I’m obsessed with these women. What a job, to make the implicit explicit for many many thousands of dollars! I talked to one consultant who’s coached hundreds of women through Rush at over 70 schools across the country. She charges four thousand dollars to help with all the social media auditing and recommendation procuring and introductory video content… but also to practice conversations, help pick outfits, and be on call for coaching and encouragement during the week. For some girls, they also help set realistic expectations: you might think you check every box to get into every sorority you want, but no amount of polish can change the fact that you come from New York and no one in your family was in Greek Life, so here are your options.

The consultant I spoke to was a Delta Gamma, like me, and I tried to charm her into letting me shadow her, but she quickly ghosted me. These women realize that what they do is in high demand, but they also realize they have an image problem. One reason these rules remain unwritten is to exclude people. The other reason is because some of the rules are deeply fucked up.

●

Whether girls hire a Rush consultant or not, most of the students I spoke with told me they spent most of their time — and money — figuring out what to wear. And for girls outside of Alabama, there are two primary resources: TikTok and The Pants Store.

If you drive from Birmingham to Tuscaloosa, you’ll first encounter the Pants Store via a massive billboard. Originally the pants store sold, well, pants. Mostly men’s. But now it’s an Alabama institution, and it specializes in whatever the college kids want: Hokas, Yeti mini-coolers, and walls upon walls of whatever’s the “right” thing to wear for Rush that year.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

The manager at the Pants Store told me that so many girls from out of state would come in before Rush asking questions about what they should buy that the company decided to come up with a full-color cheat sheet to help them shop.

“If you wanna look like a TikTok Rush girl, then you would shop there,” Emie Grant, an Alpha Chi Omega who graduated from UA a few years ago, told me. I met her outside the Pants Store one morning, and she confirmed for me that this place is basically the “Rush uniform store” — lots of “ruffles and flouncy stuff and bright pink and bubblegum pastel colors and sparkles,” which is exactly what the sororities are looking for. (And relatively modest: another sorority member told me the best look is your absolute cutest dress you’d still wear to Easter Sunday).

A bit more of my interview with Emie, who grew up about an hour from Tuscaloosa.

Emie graduated a couple of years ago, and loves to talk about her time at UA the way anyone who’s doing some real processing work likes to talk about the past. She's got long, straight brown hair, great eyebrows, adorable dimples when she smiles. And she's tall — 5'11''. When I met her, she was about to finish her MA in Gender Studies, and was riding that particular high that comes with realizing that you don’t have to deal with other people’s bullshit. But I could tell that it wasn’t always that way — that, like me, she spent a lot of time trying to figure out how and where she could fit in.

In high school, Emie orbited around the popular girls, but was never a part of the in-group. She always knew she’d Rush, but she also kinda hated it. It was loud, overwhelming, and — again, this can’t be overstated — so, so hot. “It's mid August, so in Alabama that's like a hundred degrees and humid,” she said. “We were all dehydrated. Girls were passing out and throwing up. I got tons of blisters, probably had heat exhaustion.”

But Emie got a bid for Alpha Chi Omega — a top tier sorority, the sort that would inspire a double-take from all those cool girls back home. After years of feeling like an outsider, Emie had made it to the inside. It was a feeling amplified the next when, as a sophomore, it became her job to help figure out which of the thousands of girls she should let in behind her. And seeing how it all worked from that side gave Emie a different understanding of the systems at play.

For instance, as a PNM (Potential New Member), it seemed like people were just randomly approaching her and starting conversations when she visited the houses. “Once I was on the other side,” she explained, “I realized how strategic this meeting of people was.” Strategic is an understatement here. It's maybe more like... a very precisely choreographed and potentially creepy performance.

Because it isn’t just the new hopefuls that start prepping for Rush weeks before it all kicks off. Emie had to show up to campus two weeks early, alongside all the other sorority girls, for “work week,” when the returning members put together their dances, their outfits, spend time practicing their sorority songs… and attend cram sessions to familiarize themselves with the 2000 girls going through Rush.

At my school, this involved little index cards with a black and white photocopied lookbook photo of the girl, their hometown, what they’ve listed as “interests,” and a little asterisk in the corner if they were a legacy. At UA, it’s a far more elaborate system. “We have slideshows of the girls with their pictures and where they're from,” Emie told me. “Their high school GPAs, their interests. And if you know the girl that comes up on the screen, you can stand up and you tell everybody about her and stuff like that. And that's how they kind of get classified.”

For Emie, work week was fun — she felt like she was actually connecting with her class as they all figured out what it was like to be on the other side for the first time. But once Rush started, it began to feel, in her words, “icky.” She was now judging strangers on whether or not they had some magical combination of Alpha Chi traits: A smart girl, a Christian girl, a pretty but not in a slutty way girl, a girl who gives back. Like so many other women going through Rush on the other side for the first time, she begins to imagine what people said about her. It’s psychologically brutal, all around.

After some convincing, Emie sings the Alpha Chi door song – the song active sorority members sing to PNMs before they enter the sorority house during Rush.

Then there was the bumping practice during the formal Rush events. What had seemed like random run-ins to Emie the year before were in fact the result of intensive choreography. Let’s say an active is having what seems like a normal conversation with a PNM. After a few minutes, a different active approaches, joins the conversation, and then a third active comes in. Crucially: each active plays a different conversational role. The first makes the PNM feel at home. The second re-emphasizes the feeling and highlights how comfortable and fun everything is. The third swoops in with the emotional appeal: I just love my sisters so much!

Actives also peel off to join different conversations — and when it comes to a highly desirable PNM (someone that a bunch of different houses want to pref them) you put your “best” rushers on them. (In my sorority, for example, there were certain actives who were incredibly skilled at convincing ambivalent hippies that sororities don’t suck). And after all of these conversations, the PNMs are ushered out the door while the actives retreat to quickly jot notes on each interaction on note cards, usually kept in little boxes hidden around the room.

At the end of every day, Emie and the other actives would review the note cards for the girls who’d come through the house that day, and then give each girl a rating. For Emie’s sorority, they’d rate girls on a scale of one to five (one being no way, five being an absolute yes). “I always was like, she was sweet. Five out of five. I gave everyone the best scores,” Emie told me. “Or I was like, she seemed great. I don't care. Let her be in here.”

But not all of the other actives approached ratings the same way. One moment really stuck with her: a girl was dropped from Alpha Chi because of nude photos — which had almost certainly been leaked by an ex-boyfriend. “I remember being appalled by that,” Emie said. “To write off a teenage girl for sending a picture to someone she obviously trusted, who then shared it was so awful to me. And it was just common practice.” (We reached out to the Alpha Chi chapter at UA about this alleged incident, but have yet to hear back).

You can understand a process as wrong and not have the skills or wherewithal to speak up against it. The Greek System, like so many parts of the culture in which Emie was raised, is very good at convincing people that their protests will go nowhere, and do nothing — save expel them from the system. And then what power would they have to change it?

Emie sees that clearly now. But back then, she was a timid sophomore, insecure in her place in the sorority and in Greek Life in general, trying to fit in the way she’d been taught to try and fit in. But going through the whole process on the other side, it made her think: What am I doing here? And what were these new girls — girls like Kylan — getting themselves into?

In this snippet, Emie tells me about the contrast between the forced friendliness of Rush and the reality of what she found sorority life to be: a lot of cattiness, seemingly pointless meetings, and cry sessions.

Kylan had made it all the way through the second last day of Rush — “Preference Round,” or “Pref Day” — when PNMs are left with just one or two houses as potential matches. That night, after more intensive “parties” which are usually more like a “watch all the actives cry about how much they love each other,” she had to make her final decision.

Do I want this house, or this one? In reality, some girls only want one of the houses, and will “suicide bid” (only rank their desired house). It’s a high risk move, but if you really don’t want to be part of the other sorority, it makes sense. The decision is complicated and sensitive and lest we forget, largely based on a handful of short conversations and reputational vibes. Remember, too: all of these PNMs are living away from home for the first time. They’ve convinced themselves that what happens during this week will dictate their entire life’s trajectory. Which, in some cases… is not entirely wrong? But you can see why things can get very emotional.

The next morning, the girls arrive early at the football stadium for the culmination of all that thought and effort: Bid Day, the final day of Rush, when everyone gathers to receive their final bids. The PNMs all wear running shoes, because the process ends with them running — like really running — down the street, sometimes as far as a quarter mile, to the open arms of your future home, like a sort of sorority girl cattle call.

The bids are already laid out on the bleachers before the girls arrive, in envelopes with names on them. There is a lot of waiting on Bid Day. One sorority sister told me she’d sweated the makeup off her face before things even got going. You’re expressly told not to look in the envelopes, but girls often hold the folders up to the sun to try to make out the vague forms of the Greek letters inside.

Like a lot of other girls on #RushTok, Kylan set up her phone on the bleacher in front of her to film her reaction when she opened the envelope. In her video, you can hear the Panhellenic representative running the show trying to keep the thronging crowd under control:

“On the count of 10, Not. Yet! You may open your bid,” she says. “10… 9… 8… 7…”

Kylan was shaking by this point. All the girls are totally jacked up on anticipation and fatigue and hope and anxiety. This was the moment when nine days of work — and it is definitely work — either pays off or doesn’t. In a way, it’s when you find out who you are — or, at least, who a group of other women think you are.

“6… 5… 4…”

Kylan’s top pick was Zeta. She told me that Zeta just “got” her. But Kylan did not suicide bid — she’d also “pref’d” Phi Mu, so there’s a chance that inside her envelope was a different future for herself at Bama.

“3… 2… 1!”

And with that, Kylan opened up her envelope, and…

Well, this moment is captured on her TikTok — it’s actually the first video I ever saw of Kylan. You can analyze it, frame by frame — and dozens of people seemingly have. It’s strange because… Kylan hesitates. People in the comments wonder whether she was masking disappointment, or whether she was simply trying to decipher the curly-cue Greek lettering inside (which is how she explained it to me).

It’s possible she’s bullshitting, but honestly, when I look at that moment of hesitation, I see someone negotiating a new reality, a new set of rules. I see the culmination of nine days of labor and imagined futures passing over her features.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

And then quickly, after that brief pause, Kylan puts her face together and is all smiles. Inside the envelope is a bid from Zeta.

The women on the microphone calls out ZETA!!! and Kylan and her new sisters run down the bleachers, out the stadium tunnel, and towards their new sorority house. Strangers line the street: parents, other students, fraternity guys already drunk even though it's barely after noon. They’re trying to see which house has the hottest new members. Once the girls arrive, the actives give them an overflowing bag (filled with “merch” specific to their sorority) and their Bid Day jersey (a boxy, stiff, canvas jersey with their house’s letters on the front that looks straight out of 1984 — a relic from old school Rush). Then, you pose endlessly for photos and TikToks. These images will effectively mark the beginning of your college experience — they have to be perfect.

And just like that, it’s the end of Rush. And of #Rushtok — at least until next year. Watching the journey of people like Kylan on #Rushtok is watching social hierarchy formation in real time. It’s watching power refine and reproduce itself. You get to see exactly how the status quo stays the way it does. Of course we can’t look away.

Kylan tells me she hardly knew a thing about sorority Rush before showing up at Bama her freshman fall.

But we’re forced to — because for the vast majority of outside observers, Bid Day videos like Kylan’s are where the story of Greek Life ends. You might still get the odd TikTok in your feed as people get ready for a DARTY (day party) or, if you follow Kylan, every other facet of her life, like the sorority house lunch options. But Tiktok isn’t invited to those parties, into the rituals, or inside the chapter rooms. You don’t know what it’s like to be taken to social standards for posting a political meme, or the whispered warnings about which fraternity guys to avoid. You don’t get to hear the conversations about which girls are a “good fit,” or get a warning for going to class without “two of the three done” (hair, makeup, clothes).

Listen, I knew from my own college experience how Rush worked. I knew how bids worked. But there was still so much I didn’t know about Greek Life at the University of Alabama — and that people began to tell me, in small snippets, in my DMs. Over the last two years, I went deeper and deeper into the Bama wormhole until one night I found myself reading my 50th post on a messageboard called Greekrank trying to figure out which zip codes you have to live in to get a bid from Kappa and realizing I might have lost the plot.

That’s part of why I wanted to go so much deeper with this series: so many people I know have been bewildered by their interest in this culture. It’s so addictive — but why? Because of the complexity? Because of the opaque social norms? Because all these girls seemingly know how to do makeup so much better than we do? All of the above, sure. But also because of the secrecy.

After Rush, the doors to the houses close. Only members and invited guests — almost all of them Greek — will cross those thresholds. And when the frat house parties kick off, large tents and tarps are often strung up to hide what goes on inside. Why go to so much effort to keep so much secret? And how, despite the tens of thousands who’ve passed through Greek Life at the University of Alabama, have they been so successful?

Privacy, ritual, exclusion — that’s the currency these organizations run on. But at Bama, there’s a secondary layer: one whose power, like all secret societies, stems from invisibility and, by extension, deniability. How can an organization wreak havoc if it seemingly doesn’t exist?

In tomorrow’s edition, we’ll talk about the most powerful Greek Organization on campus, one whose name students and faculty still whisper like a character in a children’s wizarding novel.

Seemingly everyone I asked about it, particularly current students, responds to questions about it with a variation of “I have to be very careful about what I say.”

Tomorrow, we talk about The Machine. ●

Further Reading:

Ready to redirect all my Olympics fervor to *this* incredible sport!

Every year #rushtok captivates me, and I hated rush myself. Rushing a sorority was by far one of the most humbling experiences I've ever had, and not for the better. Yet, being in a sorority was one of the most important and rewarding ones-- and I've been out for a decade! Recruitment is not sorority life, and most alumni would agree.

If you're in it for the right reasons, recruitment is a blip on your radar as a sorority girl. The day-in, day-out routine of living, eating, studying, bathing, gossiping, fighting, and watching TV with 100+ young women looks nothing like this highly polished and choreographed iteration of Being In A Sorority. The OU Kappas are capturing this in perhaps the most honest way I've seen.

Sorority girls, when not being filmed for content, are.... girls. They are weird and gross and insecure and come from all walks of life. They are funny as hell and sharp and, yeah, a little conceited, but who isn't? I attended an SEC school (2011-2015, so the height of TFM and the like), and even then, I was enamored by the performance of being a sorority girl vs. the reality of being one. Within the chapter house, we were loud and crude and honest. Once we left-- you're always wearing your letters, IYKYK-- we became less of ourselves so we could fit the larger mold of sorority girl established for us by generations before.

Every year when rush rolls around, I wonder, "What would sororities be if we didn't have these expectations to live up to?" For me, being in a sorority was a safe place to learn and grow because it was an intensely female space that, by the way, there aren't a lot of! Schools that do informal NPC recruitment and the NPHC organizations know this inherently. Community and belonging can't be fostered through performance, but rather, through relationships and honesty.