Memoir of a Broken Safety Net

"What it can mean to survive deep loss and keep living without losing yourself entirely, without self-recrimination or self-punishment."

Hey do you read this newsletter every week?

Do you forward it or text it to your friends??

Do you value the work that goes into it???

Consider becoming a subscribing member. You get access to the weekly reading recommendations, the bi-monthly massive link posts, the knowledge that you’re paying for the things you find valuable….

Plus, you’d get access to this week’s really great threads — like yesterday’s full of ideas of what to actually watch when you sit down and say to yourself/your partner/your cat WHAT SHOULD WE WATCH?? and last Friday’s really fucking wonderful discussion of “What’s Your Favorite Part About Being Queer?”

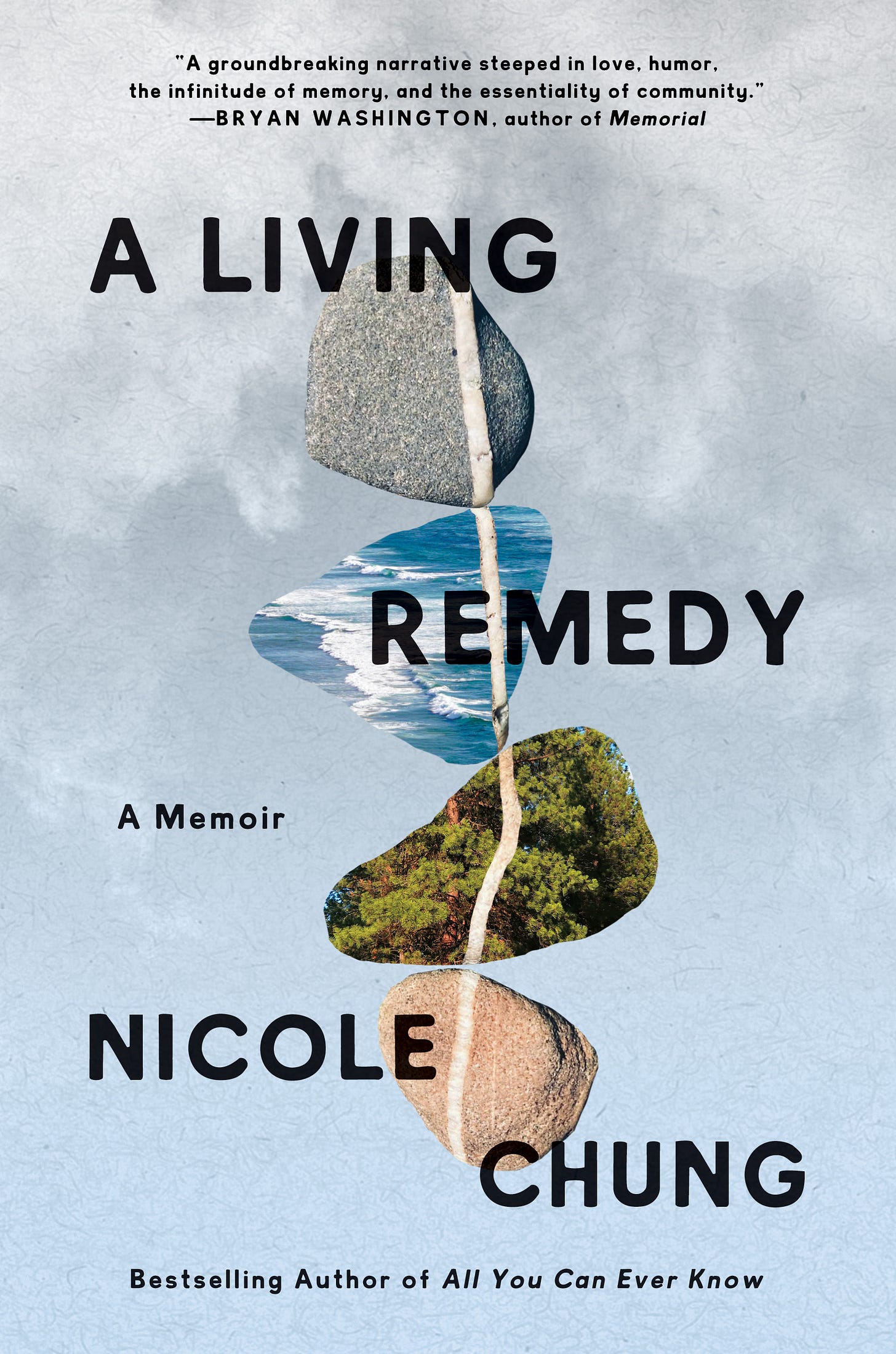

A whole lot of you know and love Nicole Chung. I know this because like me, a whole lot of you have been reading her since her time at The Toast (RIP), where she became a regular editorial presence between 2013 and 2016 (WOW IT WAS THAT LONG AGO) where she was responsible for such classics as “If LeVar Burton and Yo-Yo Ma Were Your Dads” (a personal fav), Positions I Am Ready to Fill in Your Charming Beach Town, and How To Tell If You’re in a Korean Drama. She also wrote a lot about inter-racial and international adoption — her own, and others — which would become the core of her bestselling debut memoir, All You Can Ever Know.

Back when I was writing for The Toast and The Hairpin, during the period of the 2010s that I now think of as the height of a particular brand of persona essay writing on the internet, I remember hearing an editor say that every person has somewhere between one to three personal essays in them — stories that are touching, dynamic, indelibly theirs. And once you’ve told those stories, maybe there’s not much else to say. I believed that for a long time — and sometimes worried that I’d wasted my own precious few. But then I realized there’s always another way to tell a story, always a new way to understand it — and, well, that life keeps happening. There’s always more to tell, if you can just figure out how to tell it.

And that’s what Nicole has done with A Living Remedy — which is simultaneously a memoir of loss (of her father, and then, shortly thereafter, of her mother), of adoption, of legacy….and of our profoundly broken social safety net. It is beautiful and enraging, indelibly Nicole’s story yet disarmingly relatable. And I know, too: she has so many more stories to tell.

You can follow Nicole on Instagram here and find A Living Remedy here.

I realize this is a difficult question with any memoir, because in some ways, the answer is just my life, but how do you describe what your book is about? And how has that answer changed from its conceptualization to its execution to its publication?

I’m a writer who relies on planning, preparation — I always say that once I’ve outlined a project, I know that I can write it. From the beginning, I knew that this book would touch on personal, collective, and generational grief, the ways in which this country abdicates responsibility for the health and wellbeing of people who live here, how we scramble to try to support and care for each other in the face of these enormous structural failings. It was the story of my grief for my father, one that would also acknowledge the systems and the safety net that failed him, leading to his death at 67.

When I started writing, I didn’t know that I would soon lose my mother, too. She was diagnosed with terminal cancer a few months after I started the book. By March 2020, she’d just started hospice care, the pandemic hit, my life was unrecognizable — all our lives were. I put the book down and didn’t work on it for a long, long time. I knew it would have to be rewritten, if I could still write it at all, and at the same time, I couldn’t really think about it—I was drowning, trying to support and grieve my mom from afar and parent and work full-time through those early weeks of the pandemic.

Because the book was about my life and also about how and why too many of us lose our loved ones in this country, I knew I couldn’t leave my mother’s illness and death out of it. But I also couldn’t imagine writing about it. I don’t remember the day I started writing again — I don’t remember what pushed me to do it. Six or seven months after she died, I threw out my outline and most of what I’d drafted and just started over.

The book still goes into detail about why and how we lost my dad when we did, after decades of financial precarity and lack of access to medical care. It’s still a reckoning with what I always thought was my average “middle-class” upbringing, and how and when I realized that’s not quite what it was, due in part to other medical emergencies our uninsured family faced when I was growing up. And it’s also about this strange, shifting part of my identity—being my mother’s only daughter — and what it meant to support and to miss and to grieve for her without having access to her. It’s about what it can mean to survive deep loss and keep living without losing yourself entirely, without self-recrimination or self-punishment.

How did you approach the prospect of essentially “reporting out” your family’s past — and how did your process differ from the approach you took with your first book?

I only realized it after she was gone, but my mother was the family storyteller, long before I was. And because she was still alive when I started this book, I was able to talk with her about it, ask her questions, check facts with her. She is the source of nearly every story in the book that is about my father, or my grandparents, or my parents’ earliest years together, or my early years. She was always a kind of bridge between me and her own past, my father’s past, other generations of our family. After my dad died, I started taking more notes when I visited with her. I wanted to be able to record some of her stories and remember our time together in detail, even though I assumed we’d have many more years together. Having already lost one parent, I suppose I was very conscious of wanting to preserve that time with my mom.

I talked with various family members for both books, raising questions during the drafting process and then seeking their comments once I had a full draft. The books also owe a huge debt to family lore, whose power I mention in the opening of All You Can Ever Know — most of us can probably think of stories we’ve heard over and over, for so long we don’t even remember the first telling. All You Can Ever Know was so closely focused on my adoption story, the questioning of it, and the search for my birth family — I quickly realized that any memory that wasn’t relevant to that highly specific story just didn’t fit in that book. It made it much easier to write than A Living Remedy (you know, except for the fact that it was my first, and I didn’t really believe I could write a whole book until I had actually done it).

Other sources that were important, though I consulted them less: years of emails and letters between my parents (mostly my mother) and me; the journal I’ve kept since I was six years old. No, the entries from elementary school were not so illuminating. But journals from high school and college and just after — and early motherhood, when my father’s health was really beginning to decline and we didn’t know why — those were crucial to establishing an accurate timeline of when certain things occurred.

I recognize that this probably isn’t the book my mother or father would have written about our family and what happened to us. A memoir needs to be true, but I know that even if all the facts are correct, the perspective and truth I have to share is my own. I’m fortunate that my parents, when they were living, understood and respected that.

What understanding of money and work and debt did your parents explicitly try to teach you — and what understanding do you think you actually took away from their and your lived experience as a family?

I knew they often tried to keep track of their incoming and outgoing; I remember, for example, tallying up what we were spending at the grocery store as we shopped, because it wasn’t an option to just throw everything we needed into the cart and check out. They warned me about credit card spending, tried to tell me to save what I earned at part-time jobs — but then I wound up having to use most of that money on basic living expenses, like clothes and shoes and food and school supplies and exam fees. They believed I’d be okay and able to take care of myself as long as I earned the college degree neither of them had, so they didn’t offer a lot of financial coaching or cautionary tales. I think they both had a lot of (understandable) anxiety around money, as well, and so it was just a subject they avoided with me.

I remember my mother once explaining that we, like a lot of people, lived “paycheck to paycheck,” and I think that phrase stuck in my mind in part because it was one of few things she did say about our family finances — my parents were so rarely open or explicit about those things. They didn’t want to worry me, and they also thought it was none of my business.

Like a lot of kids, I was learning about our financial situation, our place in the world, class differences, etc., not from what they told me but from what I observed and inferred. I took “paycheck to paycheck” to mean that we had just enough to get by, which was true, I think, when I was young. But that stability was deceptive, as I write in A Living Remedy, and dependent on everything going right for us. In high school, things went very wrong: my mom needed surgeries, my dad got sicker, they both experienced long periods of unemployment. We didn’t have insurance, but they both went through major medical crises, and the debt, I now know, ballooned during those years. It would eventually bankrupt them, although I didn’t know that until their papers came to me after my mother’s death.

All this to say: I didn’t have a firm understanding of the situation at all. Even when my mother was very sick and needed me to assume financial power of attorney responsibilities, it was hard for her to let me manage her affairs. That was not supposed to be my role as her child, in her mind — she was supposed to take care of me, not the other way around. It was one of the toughest things we had to learn to navigate all too quickly, together: our changed relationship and responsibilities and roles as dying widow and only daughter. I wanted to be able to take care of her, but that was something that was really hard for her to accept as my mother.

I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about how the deterioration of the social safety net in the US puts people in scenarios of “coerced” care — e.g., where they don’t get to choose the terms of how, when, and why they care for their family members; instead, an utter lack of options (societally but also within the family) forces them into the position of care-giver.

The ramifications are coerced care are so wide-reaching — in the worst scenarios, it can lead to bad care, but most of the time, it just leads to a lot of anger and resentment, which can be especially hard when you’re caring for someone at the end of their life. How would a real and robust social safety net have helped change the terms and tenor of care that you were able to provide for your parents? Put differently, how would more choice, more options, more assistance have changed the way your parents were able to be there for each other in sickness, or how you were able to be there for them?

While much of the discussion around A Living Remedy has (justly) focused on our broken healthcare system, I felt it was very important to be explicit about the many ways in which the safety net failed to catch my parents — it wasn’t only healthcare inequality and inaccessibility that they were up against.

As my family experienced, assistance in this country is scant, gatekept. The rules and requirements and what’s available can vary so much depending on where you live. We get endless lectures about “personal responsibility” and are then urged to blame ourselves, or each other, when these systems that weren’t actually built to help or serve us prove inaccessible. When my father was still alive but very sick — he was in late-stage renal failure, and we had no idea because my uninsured parents couldn’t afford the testing and specialized care he needed — it was hard for them to accept that they were at a point where they needed to apply for rental assistance, Medicaid, and in my father’s case, disability benefits. I remember helping them research what types of assistance were available, once they finally agreed to try. None of us were experts in any of this, and it was incredibly daunting.

I felt sure they would qualify for some kind of help, because at the time they literally had no income. My mother was selling her plasma. But they were both still too young to qualify for Medicare. My father’s disability claim was denied, as is so often the case. They were denied coverage through the Oregon Health Plan (Medicaid). They had no dependents, and their cost of living was considered too low to qualify them for anything else. The social worker told them they both just needed to find jobs, which they had been trying to do for over a year and a half. In the end, my father was diagnosed with late-stage renal failure only because he got off the waitlist for an appointment at a federally qualified health center. He was finally approved for the Social Security and Medicaid benefits he’d been denied, but by then, so much damage had been done.

With my father, whose illness was exacerbated by years without the healthcare he needed, it was really hard to come to terms with all that I couldn’t do for him. Especially after he died. It was hard for my mother, too. I grew up thinking of my parents’ future needs and care as my responsibility, part of what I owed them as their child — I think a lot of people feel this way. And that might work for some small number of people — if you’re privileged enough, wealthy enough, live or can move near your parents or have space in your home for them, don’t need to work all the time, don’t have children with significant needs of their own, and you all have health coverage. Even then, it’s hard; it’s expensive; it takes time and energy and the kind of planning that is really hard to do without knowing the future. It can feel very isolating.

Medicare doesn’t cover the kind of long-term care people often need; nor do most health insurance plans. When my mother was dying and needed home health aides to assist her family caregivers at night, I was writing checks for thousands of dollars per week. I couldn’t have done that for long. We had no other wealthy family members who could have paid for her care. And Medicaid, which I was ready to apply for on her behalf, would have taken weeks or months to be approved, and even then it would only have covered a fraction of the care she needed.

If you’re someone who is dealing with that or a similar situation, trying to meet some health crisis, you’re made to feel like it’s all on you—because, in a very real sense, it is all on you, even if the need far outstrips your capacity. And so when a crisis hits, there are truly no good options unless you have access to vast wealth. If my parents had been able to find the support and help they needed when they needed it, it wouldn’t just have spared us all a great deal of harm and heartache and stress; it might have prolonged my dad’s life.

As we have all seen and experienced during the pandemic, a focus on personal action and responsibility and “bootstrapping” can’t address systemic problems. Individuals, communities, can do a lot, but the need will continue to expand and push too many people to the breaking point. As I grieve, I still have to remind myself that I was not responsible for structural failings, or the systems that failed my parents. That my dad’s early death, especially, was not inevitable, and that it was also one of far too many like it in this country.

There’s a throughline in the book of inheritance — how we often understand it as running through blood lines, how your own adoption challenges that, how we inherit the consequences of financial obligations and postures and decisions, but also how we can inherit warmth, and grace, and understanding — which can then be cultivated and passed down to the next generation. There’s a point when your dad has died and you’re texting with another parent, and that parent says something to the effect of “you’ll see him live on in your own children” — and you pause, and realize she doesn’t know you’re adopted, and that you won’t see his features in your own kids. But as I finished the book, I found myself thinking about how many of the characteristics you attribute to your parents manifest in your own writing and personality. What of your parents do you see, or hope to continue to see, in your kids?

I rarely think about my kids as being products of my birth and adoptive and chosen families, even as I recognize that all these people and connections are part of the legacy I want to leave them. Maybe as an adoptee, I’ve always been extra skeptical of the claims some people love to make about inheritance—the desire to focus and repeatedly comment on what are seen as similarities between one relative and another, one generation and the next—because I grew up outside that kind of framework, in a family to whom it was important, and always felt out of place even though I was very much loved. Like, I’m probably less likely to think, “oh, she gets that from ____” and get a little thrill from that than someone who wasn’t adopted. At the same time, I do recognize that if my kids have inherited anything from anyone else in the family, it’s probably because I inherited those things first? All my life, I thought that I was so different from my adoptive parents, and wondered how in the world I got to be the way I was if “nurture over nature” was such a thing. Now that they’re gone, I can trace so much of who I am to who they were, either because I inherited those traits or chose to react against them.

To answer your question: I can think of obvious things, like how my kids often found my dad hilarious. On some level, I think my older daughter, especially, just got his sense of humor in a way I didn’t, and I remember thinking at one time before he died that that was a little gift I’d given my father (without really intending to, because of course that’s not why I had kids). What’s most important to me as a parent is that my kids are kind, happy with themselves, happy in whatever kind of lives they want to live, able and willing to help others. If you asked my parents what they wanted for me, they would have said something very similar—their love and respect for me, their faith in who I was, was never about anything I did or anything I achieved.

My sense of identity and self-worth is too wrapped up in the work I do, and I’ll be trying to untangle and address that all my life, but because of who my parents were and how they parented me, I could also base my self-worth on other intangible but very important things. It took a long time, but I finally learned to show myself compassion and grace, and I think it’s partly because they always let me know that I was enough for them — without action, without proof, without accomplishing anything in particular, I was enough. It’s probably their greatest legacy to me, if you want to think about it in terms of legacy. I really hope to be able to give my kids that same foundation, to let them know I have that rock-solid faith in them even if they don’t yet have it in themselves. ●

You can follow Nicole on Instagram here and find A Living Remedy here.

If you enjoyed that, if it made you think, if you *value* this work — consider subscribing:

Subscribing gives you access to the weekly discussion threads, which are so weirdly addictive, moving, and soothing. It’s also how you’ll get the Weekly Subscriber-Only Links Round-Up, including the Just Trust Me. Plus it’s a very simple way to show that you value the work that goes into creating this newsletter every week!

As always, if you are a contingent worker or un- or under-employed, just email and I’ll give you a free subscription, no questions asked. If you’d like to underwrite one of those subscriptions, you can donate one here.

If you’re reading this in your inbox, you can find a shareable version online here. You can follow me on Twitter here, and Instagram here — and you can always reach me at annehelenpetersen@gmail.com.

It's so hard - there's no central resource of help available (a page of links is not help), there's so much more need than help available (which is only going to get worse), and people want to believe that it won't happen to them so they do mental contortions to make it seem like it was a matter of bad choices instead of the luck of the draw. It was my primary source of anxiety as I would do the math every week of how long we could afford to keep mom in memory care. The rates went up (those increases went to better wages, so I was happy for that) and memory care was only an option because of the survivor benefit from dad's pension. Not many of us have those anymore. It's something we're going to need to reckon with as a society.

Oh man, as someone on the verge of having to apply for Medicaid for a parent who is outliving his remaining assets this hits home.