Many of the people who read this newsletter the most are those who haven’t yet converted to a paid subscription. If that’s you, and you have the means, consider paying for the things that have become important to you. (If you don’t have the means, as always, you can just email me and I’ll comp you, no questions asked). Subscriptions make work like this possible.

When I was in fourth grade, we had a system in the classroom intended to incentivize reading. Books in the library were given point scores; after you finished one, you’d take a comprehension test on the classroom Apple IIe to confirm that you had, in fact, read it. After a few weeks, I realized I could win the class-wide competition by going for the highest-point book available: Charles Dickens’s David Copperfield. I read it. I understood very little. I failed the comprehension test. I still won the contest. There was no reward.

*

My first year of grad school, the only internet I had at home came when the signal from across the street happened to pulse strong enough for me to refresh my email. The theory I was reading was dense to the point of impossibility. Sometimes it’d take me two hours to get through ten pages, going back and reading, re-reading, trying to write down the idea in my own words to make it make sense in my mind.

*

The first week after I moved to New York, feeling adrift and very alone, I allowed myself to sink into Melissa Abbott’s The Fever on a hot Saturday afternoon. It was the first time in a very long time that I’d finished a book in one sitting. I felt indulgent and deeply attuned to my own emotions, in a way I hadn’t felt since I had found myself accidentally enthralled by the Twilight books. It was delicious.

*

In 2018 I decided that reading more books would be one way I would recover from burnout: I would do what I actually wanted to do, instead of doing what my phone encouraged me to do (specifically: hang out with my phone). Other people were making spreadsheets of the books they’d read and tallying them and setting goals; I would too. 50 books in 2019. I did it, but the feat itself weighed on my mind constantly: am I reading fast enough to keep on pace? Should I pick a shorter book next, or avoid this longer one? It felt less like reading and more like optimizing my reading. I remember very little.

*

I lost reading during the pandemic. It makes sense — when I was burned out, I couldn’t do the things that I wanted to do, and those first five, six months of the pandemic, seemingly all I did was work and look at Covid counts. I tried everything the articles and Twitter advice told me to try: I used plotty thrillers and romances to pull me back on board, I put my phone in the other room. Sometimes it worked. Sometimes I’d start and finish something I loved. But a prevailing image of the pandemic is the three half-finished books on my bedside table — books I liked, books I wanted to finish, books I couldn’t bring myself to. I was still reading books for this newsletter, but I was reading them poorly, my attention attenuated. Same for basically everything I read online. My reading was becoming weaker; my comprehension, diluted. Was I becoming a hack?

*

Back in New York to give a talk with a free afternoon to walk through the Village in gorgeous Fall weather: the sort of moment that almost, almost makes you want to move back. I walked by McNally Jackson, started to walk in because I always walk into a book store, and scolded myself: you can’t even read the books you have, you’re not allowed to get any more.

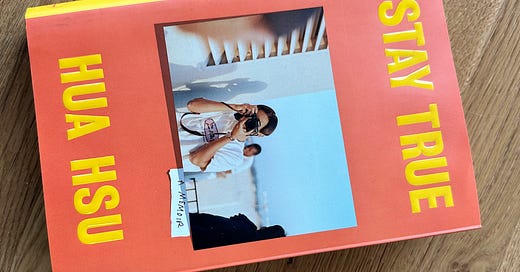

In that moment, it occurred to me, as if a revelation, that if I made the decision to read the books, if I did the damn thing, then I could do the other thing I wanted to do, which was to buy more books, have more books, have read more books. And so I walked in, bought Hua Hsu’s Stay True, and put myself to the test.

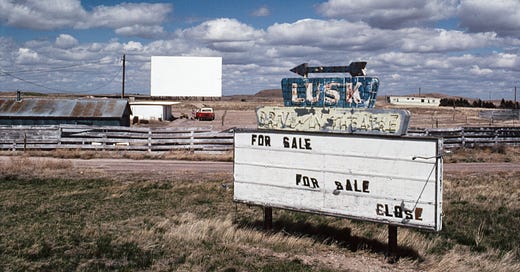

Strength of will can’t change most things but it can change some, particularly for people as stubborn as me. I came home and effectively decided to form a new habit: read every night, no matter what, even if it’s just a few pages. I didn’t tear through Stay True, but the twenty to thirty pages a night allowed the story — a memoir of Hsu’s college years at Berkeley, the child of immigrants, obsessed with music and uniqueness and his best friends, one of whom dies in an utterly random act of violence — to seep in, hang out, stay with me. I moved to Bobby Finger’s The Old Place, about a tiny town in Texas loosely based on Finger’s own tiny hometown, and am finishing Laird Hunt’s Zorrie, an exquisite sliver of a book equal parts Elizabeth Strout and Marilynne Robinson.

I brought my book to the hair salon and actually read it. I sleep better when I’m with someone else’s world before falling asleep into mine. I’m buying more books and find myself ravenous for them. I don’t feel the need to write down how many books I’m reading. I don’t feel that I need to read more, or a certain type of book best for social media. I personally like reading the physical book but understand why others find audio books or digital books more conducive to this posture. I spend time in the Discord group, started by Culture Study members months ago, that echoes my affection for reading, my anger at how I lost the joy of the process, my renewed and focused will to regain that habit. Its name: READING IS IMPORTANT TO ME AND I WILL PROVE IT.

I’m thrilled just to be back here, in the throes of what once felt like such a standard part of my life and understanding of self as to be unremarkable. It’s basic, it’s true. I’m a person who loves books and, perhaps even more importantly, loves to read them.

*

I’d been thinking of these ideas for several weeks when an episode of Ezra Klein’s podcast popped into my feed: a conversation with literary scholar Maryanne Wolf about how different modes of reading activate different parts of the brain. (You can also find a written transcript of the episode here, if a podcast is not your thing right now).

For all the value of the skim (and it truly is a skill!) Wolf emphasizes what’s lost when the skim is all we do: we fail to reach that immersive, focused state, which isn’t just a font of understanding (the text, an idea, a theory) but of wisdom (applying or extending that idea to one’s life, layering it upon another idea, finding empathy for someone whose situation is not your own).

Some of Wolf’s takes on, say, children and screens strike me as alarmist, but the idea that reading is never just about what we read, or how much we read, but how we read — it tied together so many of my frustrations with past incentives to read, and my own quiet fears about my ability to focus on the ideas in front of me.

Importantly, I was able to draw these connections because I was focused on the conversation the same way I would’ve been focused on a book: I was driving a route I’ve driven hundreds of times, with no one else in the car. Wolf was describing the way a mind lights up when a parent reads to a child, how the imagination is activated when you’re in total concentration, and it was the dorkiest but most delightful feeling — feeling the same happening in my own brain.

And I think this is what I needed — encouragement to read not just because reading somehow makes us seem like better or more accomplished people, not because it fulfills an arbitrary goal, but because it awakens something elusive and precious inside of us. As Wolf reminds us, quoting Aristotle — “all the books in the world will not bring you happiness — but build a secret path towards your heart.”

*

So what’s helped you? Not just to read more, but to read with more focus — and towards more wisdom and empathy? I’ve been talking with readers on Instagram and in Discord about this topic, and the overwhelming consensus is that you need to extract yourself from your phone’s demands (which, depending on your relationship with your phone, might mean putting it in another room, downloading an app like Forest, or reading on your phone because that’s enough to prevent you from clicking out).

I don’t just want to know your tricks, I want to know your mindset shifts, your corny existential reconsiderations of reading’s place in your life, your struggles with doing the thing you really want to do. If you were writing a play of your reading life, what are the acts — the little memories, like the ones I outlined in the beginning of this piece — that led you to this stubborn commitment? And how are you making time and space to build that secret path towards your heart? Why is reading important to you, and how will you prove it?

Subscribing is how you’ll access the heart of Culture Study. There’s those weirdly fun/interesting/generative weekly discussion threads (this week’s is Friday thread on perfectionism and ambition was particularly good), and the rest of the Culture Study Discord, where there’s dedicated space for the discussion of this piece and the latest episode of the podcast, plus really useful threads for Job-Hunting, Houseplants, No Kids Club, Chaos Parenting, Fat Space, Productivity-Culture, and so many others dedicated to specific interests, fixations, obsessions, and identities.

If you’ve never been part of a Discord: I promise it’s much easier and less intimidating than you imagine.

As always, if you are a contingent worker or un- or under-employed, just email and I’ll give you a free subscription, no questions asked. If you’d like to underwrite one of those subscriptions, you can donate one here.

If you’re reading this in your inbox, you can find a shareable version online here. You can follow me on Twitter here, and Instagram here — and you can always reach me at annehelenpetersen@gmail.com.

TECHNICAL GLITCH (AND ALMOST CERTAINLY USER AKA AHP ERROR) —> links didn’t make it into paid subscribers’ emails. My apologies, and look out for them in Tuesday’s thread prompt!

As a longtime high school English teacher I often struggled to keep my own reading interests alive. I think I went through a drought of about a decade once, where all I did was reread the novels I was assigning to my students. Pandemic had the opposite effect on me: I read and read and read. I read almost 40 books between the shutdown and the end of 2020 and maintained that pace afterward. There was a theme in those books: a lot of running books, a lot of books about racism, and a lot of books about survival such as Endurance by Alfred Lansing. I needed to understand the world I was living in. Since my divorce in 2021 I have read a lot of books about women’s rights, and about solitude, and about nature; you can guess, based on those, how I’ve been spending my time. “Proving” that reading is important? I have a former student who was a wonderful reader and thinker. She had a terrible home situation and all of us teachers hoped and dreamed that she was going to “make it out.” But two nights before graduation she committed a terrible crime and is now in the state women’s prison for 20+ years. I’ve started writing to her and learned I can order books for her. So I think we will read some books together and talk about them via pen and paper, very much like...and not at all like...the old days.