Make sure you check out this week’s ADVICE TIME — so many opportunities to ask for/receive advice from strangers on the internet!

And if you want to laugh about very unserious shit: go listen to this week’s episode of , featuring the great Krista Burton of . You can find it (and a bunch of big gnome feelings) here.

And remember: your subscriptions are what keep the paywall off posts like this one, which make it possible for everyone to read and share the work of authors you might not otherwise encounter. If you value this work and want to keep it accessible, subscribe today — plus you get access to all the threads!

When I was young, probably around 7 or 8, I found myself watching something on television that I wasn’t supposed to. Or, more precisely: something on the USA Network that wasn’t within the realm of my “normal” shows. It was just for a little snatch of time, but there was a hospital, and a woman giving birth, and a lot of thick, deep red blood. For years after, that image would sometimes re-appear, utterly unbidden, when I closed my eyes to concentrate on something. The brain is wild, right? But that image imprinted on me. Birth and horror, intermixed.

I don’t think that has anything to do with me not becoming a parent, but I do think it’s part of my general suspicion of birth narratives. I don’t like pain. I don’t like its glamorization. I don’t like what seems to get obviated in gauzy narratives of it was all worth it. Kids are amazing, and it’s amazing that bodies can birth them, but there’s a lot of body horror involved, too. The reticence to speak frankly about it (apart from “it’s the hardest thing you’ll ever do”) always made me suspicious. Were birthing parents just telling the truth behind closed doors without me? Or were they, too, beholden to narrative tropes of how to understand their own experiences?

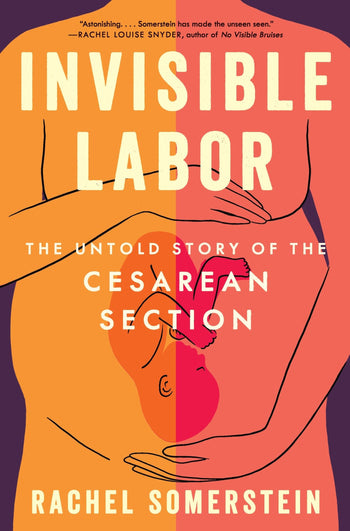

I wanted to understand how our stories of birthing get shaped, how trauma and pain are narrativized within them, and how both speak to larger, racialized understandings of the value of women’s bodies and their pain. And I’m so grateful for Rachel Sommerstein’s book Invisible Labor: The Untold Story of the C-Section for providing just that. If you’ve experienced a traumatic birth and have yearned for someone to understand it or at least talk about it with: this book is for you. If you had a “standard” birth but still feel like there’s so much to interrogate about how we talk about choice, consent, and pain in the birthing process — this book is absolutely for you, too. And if, like me, you haven’t given birth but are invested in taking women’s pain seriously — read on.

**This interview includes mention of traumatic birth experiences. If you’re not in the place to read that today, or any discussion of pregnancy, pain, and trauma, give yourself a pass on this one.**

Let’s start with some table setting. The book’s subtitle promises “The Untold Story of the Caesarean Section.” What’s the *told* story? And because this is a personal book, what was your relationship to that story – both before and after you had your own c-section?

The told story is that C-sections are easy: “designer deliveries” for people “too posh to push.” This story is starting to shift, but as I was thinking about your questions, I came across someone on Threads who asked why women would go through with labor when they could just have a cesarean. It’s easy to pile on to people who say that kind of thing, especially when they're a stranger on the internet. But that idea came from somewhere, and it’s still ambient: that an operation that involves cutting or parting through seven layers of tissue is easier than labor. A shortcut to birth.

And their perceived easiness is, I think, associated with the other story that’s told about them: they’re a second-class way to birth.

And that’s what my relationship to c-sections was like before I had one. I thought they were somehow less honorable than vaginal birth. I also thought they didn’t happen to people like me, because I was a “natural” type: I do yoga, had hired a doula, I don’t eat meat. I prefer to walk over driving. If asked why I wanted to have a vaginal birth, I probably would have said something about how that would lead to a more natural connection with my baby.

But also, and though I probably would have been too embarrassed to admit it, I thought that the way I birthed reflected something essential about my character. A vaginal birth meant I was a more authentic person — the mom who goes through the trouble of making the cookies from scratch rather than buying them from a store. I now know that the way you birth has nothing to do with your character. What it often does reflect is the culture of the place where you have your baby and the training of the people taking care of you.

Now that I’ve been through one, and have written Invisible Labor, I have a lot more respect for the operation. I have gratitude that it exists for mothers whose babies need to be born that way. But I also respect it for how significant it is: major, abdominal surgery that will continue to impact you long after you’ve “recovered,” from shaping the future of your reproductive life, to raising the likelihood you’ll need a hysterectomy later on, to many other changes that I call the “cascade of consequences.”

As an example, I developed what ended up being diagnosed as chronic appendicitis in the summer of 2023. It didn’t present like acute appendicitis, and when I first went to the gastroenterologist, he suggested that the pain I was having might be caused by adhesions from my c-section. My jaw dropped. This was seven years after I’d had my baby, and no one had ever told me that developing that kind of pain was even possible—that abdominal adhesions could do such a thing. To be clear, that kind of outcome is a risk following even a textbook cesarean, but one that you don’t usually find out is a possibility unless you stumble into it yourself. So I’d say that I now think of my c-section as like a shadow that follows me around, making itself known at times that I’d expect — like when I look in the mirror naked and see the shape of my body — and also asserting itself in surprising and unexpected and often unwelcome ways.

I was pretty horrified (but not surprised) when you connected the dots between the development of the c-section and the desire amongst slaveowners to “salvage” as much property as possible (by saving both mother and child during childbirth).

Can you talk a bit more about how the c-section was developed and practiced and its legacy — particularly when it comes to consent and control and understandings of pain — today? (Maybe a chance to talk about Victoria’s story??)

It is horrifying — and unsurprising.

One thing that’s important to keep in mind is that c-sections developed to address a tragic problem inherent to birth: some babies can’t get born vaginally. They get stuck. In such circumstances, and without intervention, neither a baby nor its mother can survive.

Today, when we say a baby is “stuck,” we’re using a much broader definition. We might mean that labor has slowed or stalled. That you seem to have stopped dilating before making it to 10 centimeters, which is full dilation. That the baby isn’t descending. Or it could be that, during pushing, a baby’s having a hard time making it through the vagina.

But before the twentieth century, a stuck baby was one that quite literally could not fit through the birth canal, no matter how hard or long a person labored. And while stuck babies weren’t common, they’re so fundamental to birth that even the Mishnah, the compendium of Jewish law that comprises statements made by rabbis from 70 to 220 A.D., addressed them.

The only way to save a mother in such a circumstance meant killing the baby to make it small enough for the mother to birth. Besides being dangerous to women and horrific for all involved, it wasn’t even always possible to do that. Some women’s cervixes didn’t dilate at all—not even enough for a physician to use the necessary tools.

So c-sections emerged as a way to save these women and their babies. But they were nearly always fatal. Until about 200 years ago, obstetricians were split about whether to even attempt so dangerous an operation on a living woman. Many objected to it on “humanitarian grounds,” and it was only rarely practiced. Because the way physicians mostly defined the operation’s success was if the mother survived—it was a failure if her baby lived, but the mother died.

From the 1800s onward, cesareans began to pass into a realm of medical practice that physicians might conceivably encounter, though they rarely did. In time, the operation evolved from one primarily performed on dead or dying women to a surgery of last resort that a woman might conceivably survive. The Catholic Church played a part in this as well, in ways I describe in the book, and that foreshadows how anti-abortion activists continue to invoke religion to shape reproductive freedoms today.

Slavery was ongoing at the time and childbearing, as historian Deirdre Cooper Owens writes, was “a centerpiece of the system of chattel slavery.” A colonial Virginia law passed in 1662 held that an enslaved woman’s children would have the same “status” as their mother. Black women thus could “build capital for enslavers” through birth, which became even more important after the US banned the transatlantic slave trade in 1808.

That’s why physicians and slaveholders were more likely to gamble on an enslaved woman’s stuck baby and do a C-section; they had a chance of saving both baby and mother — and adding to their stable of enslaved people, Cooper Owens writes. They were willing to take this risk because enslaved people’s lives were expendable, and because an enslaved woman’s value was linked specifically to her capacity to bear children and enlarge her master’s wealth. To make it clear the degree to which Black women were more likely to have c-sections than whites, there is no record of a white woman in Louisiana having a cesarean until 1867 – even though one of the pioneers of the surgery, Francois Marie Prevost, lived and practiced there. (At the time of his death he’d enslaved 40 people, including 10 children.)

And while consent looked nothing the way that it does now, at the time, enslaved women were not asked if they would submit to the operation — their enslavers were consulted. By contrast, as historian Jacqueline H. Wolf has written, physicians asked everyone present at a white woman’s birth, including the woman, if it was OK to proceed. (There’s plenty of evidence that they often browbeat these women too, to be clear, but enslaved women weren’t even asked.) The stakes on obtaining this form of “consent” matter because at the time, c-sections were nearly always fatal to the mother. Also, Black people were believed not to feel pain as deeply as whites, which is still an issue today — Black women are less likely to have their pain treated than white women.

This history continues to shape the contours of contemporary obstetric practice and cesareans in particular. First, Black women are still disproportionately more likely to have c-sections than white women. A new study of 1 million births in New Jersey showed that even when Black women have the same doctor and are birthing in the same hospital as white women, they are 20 percent more likely to have a c-section. The role of racism in cesareans and obstetric care is so entrenched that even efforts to bring down the c-section rate that have been successful, like ones by the California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative, have seen racial inequities persist.

Many women I spoke to for the book experienced combinations of racism—interpersonal, structural, systemic—in ways that coalesced to result in surgical births that might not have been medically necessary. Victoria Williams, for instance, whose story I tell in the book, is incredibly knowledgeable about birth. She’s a doula, holds an MSW, and was completing her doctorate when I was writing the book. She’s Black. She’s had three c-sections: one following a failed induction; a second, ten years later, after being coerced by her physician; a third for similar reasons. For her second and third births, she was shut out of other, less-interventionist midwifery care. It’s important to point out that scheduling a c-section or seeing an OB are perfectly fine choices, but that’s not what Victoria wanted, and it’s not what she conveyed to her providers. But they didn’t listen to her.

Victoria’s expertise, her credentials, her lived experience — none of that mattered to the way she was treated. And none of that changed the fact that she’s birthing in a racist system. And as a consequence, you have someone who had at least two, and possibly three, medically unnecessary cesareans, and all of the downstream effects that those operations set in motion.

“The history has been written for Black women,” she told me. “They are the people who have been experimented on. History has already told [doctors], ‘They have a high pain threshold. They have high blood pressure. They don’t eat well. They’re stressed out. They don’t have social support.’ History is showing them how to treat us.”

I understand what she said to mean that obstetrics is but one area in which all of us — doctors, patients, no matter what ethnicity — are living with what scholar Saidiya Hartman calls the “afterlife of slavery.” Alicia D. Bonaparte, a Pitzer professor of sociology who shared Hartman’s ideas with me, noted how very embodied the afterlife of slavery can be: from police use of deadly force, to the ways that missing women of color rarely make the news, “your lived experience [as a Black person] is a reminder of the fact that you are not even considered as a human, but as a body.”

You write that “there’s still no way to have a baby entirely without pain, during labor or after birth. That pain can be terrifying, empowering, both, or neither. But it is most certainly normal. Unfortunately, because birth has been medicalized, it can be hard to expect — or accept — this reality. Medicine, delivered in a hospital, is supposed to make the pain go away. With childbirth, it can’t. Not entirely.” You point out that trauma is not usually the result of the extent of the pain itself, but the way others react to expressions of pain: “Pain that’s diminished or dismissed causes damage that lasts.”

A few days after one of my best friends had her baby, I came over to visit and her face was covered in burst blood vessels. “That was so horrible,” she said, just kinda shaking her head. Today, she has no memory of the conversation. She didn’t have a traumatic birth in the way you had a traumatic birth, but I think there are so many overlapping physical and psychological encouragements to forget, erase, or otherwise omit trauma from the birthing story. What’s at work here — and what’s lost when we continue that narrative?

This is such a good question. I think part of what’s going on is that we still do not recognize women’s pain. If you’ve had a tough birth, or felt traumatized, people will sometimes come back with, ‘But you have a healthy baby, and that’s all that matters.’ Of course you want a healthy baby, of course that matters, but how can that possibly erase what you’ve been through?

I think that kind of auto-response is more about diverting or shutting down a conversation from a person’s pain. And yes, it can be unbearable, and frightening, to confront someone’s pain. You might not know what to say or feel overwhelmed by your inability to make it go away. But what’s also going on here, I believe, is that we live in a society that routinely diminishes, ignores, and underestimates women’s pain from the time that we are children.

A recent piece in the New York Times pointed out that only 5 percent of providers use pain relievers when inserting an IUD. That it’s 2024 and using pain relief during that procedure isn’t standard of care tells you everything you need to know about what women are routinely expected to tolerate. And, we all become habituated into this. It is the very air we breathe. It’s like thinking your water or your food doesn’t have microplastics in it. Misogyny and patriarchy are ubiquitous even if you can’t see it. That’s how ideology works.

The consequences of turning away from or shutting down these stories are problematic for so many reasons. First of all it’s isolating and stigmatizing for the person who’s been traumatized. Second, it doesn’t prepare people for what birth can be like. And while you don’t want to scare people, avoiding hard topics doesn’t protect a person from them. The last thing I want to think about, for instance, is my own death, but guess what — I wrote a will anyway. Avoiding something doesn’t mean it won’t happen. And, it continues our tendency to diminish or avoid women’s pain.

I also think that the fact that birth can be traumatizing, and that we turn away from that fact, shows the extent to which birth is beyond our control. Some trauma CAN be prevented: being listened to by your providers is essential for that, and we’re doing too little to research and implement strategies to prevent postpartum PTSD, for instance. But also, the truth about birth is that sometimes, unexpected and difficult things happen.

That birth is beyond our control forces us to look more squarely at it, and also, by extension, at new motherhood and the unrealistic expectations we have about the postpartum period. It isn’t a neat story of, ‘You went through something hard, now baby is here, the end.’ The real narrative is more nuanced and complicated and produces all kinds of conflicting feelings that change all the time.

You’ve gone through one of the most fundamentally transformative experiences that a person can experience. You have brought another BODY into the world, through the portal of your own body, in a misogynistic medical system that increasingly prioritizes speed and efficiency rather than humanity and human connection for patients or providers. Also, it hurt. And now you have to care 24/7 for a new baby on very little sleep. And our response to that is to expect you to go on unpaid leave for three months? If you’re lucky? Oh and by the way here’s a 30-minute meeting with your provider to, ostensibly, process your birth, get cleared for exercise (whatever that even means), get birth control, screen for a postpartum mental health disorder, get help with breastfeeding or formula feeding, talk about the pelvic floor and diastasis recti, and make sure any chronic stuff that got kicked up during the pregnancy is in order.

That brings me back to the beginning of my response here, which is how terrible we are as a society at recognizing and addressing women’s pain, which can include the growing pains of adjusting to new parenthood. How unbearable is it to really look in the face the degree to which, as a culture, we’re consistently abandoning new mothers and that in doing so we’re both perpetuating and ignoring their pain? Trauma itself can be overwhelming, but so is the ocean of need in a new parent facing also, let’s say, financial precarity, or emotional isolation, or an untreated postpartum mental health disorder, addiction, sadness, bone-deep exhaustion, difficulty breastfeeding, even the joys and sorrows of the ways a dearly-wanted baby changes a family dynamic.

That is the consequence of ignoring real birth experiences, of narrowing the story to, ‘It was rough, baby’s fine, the end:’the inhumane system we’ve created, where we shove mothers back to the responsibilities of their pre-birth lives, sometimes only a few weeks after having a baby, without a shred of the care they need emotionally, physically, or spiritually.

You address this a bit in the book, but I have a theory that part of the reason there’s such poor care around c-sections is that the rhetorical focus has been on destigmatizing the c-section — that it’s “just as good” as a vaginal birth, just as “natural,” in a similar vein to some of the conversation around formula vs. breastfeeding. So instead of doing the much harder work of figuring out how to avoid c-sections, or how to provide much better pre- and post-op care, it’s just that was just a birth like any other instead of “that was a major surgery and there are all these things that we should be talking about and aren’t because we’re so focused on pretending like it wasn’t a big deal!”

And the the worst part is — there’s still stigma! Mothers still understand themselves as “failing” at childbirth in some capacity, or at the very least that their bodies in some way “failed” them. I’d love to hear you expand a bit more on a more effective strategy.

This can be a really hard needle to thread, as you point out, because you don’t want to contribute to the “failure” narrative. But you also don’t want to smooth over the reality, which is that surgical birth is not easy and often not a person’s first choice.

I think that changing the way that we talk about c-sections writ large — in the public culture AND in birth education — is key. We need to give c-sections more respect, and by that I mean, we need to recognize how invasive they are. You might only see a small scar on your skin, but a c-section is organ surgery. Going through it and then caring for a newborn 24/7 is a serious feat. Too posh to push? Believe me, it’s not posh to change diapers when you can’t even stand up straight. It’s hard enough to adjust to new parenthood, let alone do so when you’re recovering from an abdominal operation. (And this isn’t to suggest it’s easy to do so after a vaginal birth either, which is also hard — the comparison Olympics serves no one so let’s stop that too.)

Giving cesareans more respect can happen in a few ways. First is to make c-sections more visible. We’ve started seeing them more in literature and TV–I’m thinking about Fleishman Is In Trouble, for instance, and And Now We Have Everything. But they can start to be a bigger part of how birth is represented in film, TV, on social media. That will help to normalize surgical birth, provided it’s represented in a nuanced way that gets at the many types of experiences there are of it: a c-section can be calm, urgent, joyful, scary, exciting, anxiety-provoking, all or none of that.

This change in how we talk about cesareans should also happen in prenatal visits, books and other resources for pregnant people, and childbirth education classes. Those are sites where everyone who is pregnant can be invited to learn about what happens during a c-section and what recovery is like. I think part of the stigma comes from experiencing the recovery part alone and feeling shame about it. Like, is it normal that I can’t stand up straight? That it hurts when I sneeze or laugh? That my husband has to help me sit up in bed? That I’m still in pain a few weeks later? Yes, and, it’s a lot less isolating, stigmatizing, and scary if you know that is what recovery may be like before you go through it yourself.

I also think that a more rigorous education would improve the c-section experience for people who have them. The first time you learn about what happens in a c-section should NOT be as it’s happening to you. As an example, one mother I interviewed experienced a lot of anxiety going into her cesarean and asked for medication for it. Her anesthesiologist offered her something, and then cautioned her that it could cause memory loss. He was 100% doing the right thing by telling her about this possible side effect. But the problem is that, 1) Rolling into the OR wasn’t the right time for her to be presented with this information for the first time (which isn’t his fault), and 2) He didn’t offer non-pharmacological alternatives to managing her anxiety, some of which it was too late for anyway — she couldn’t snap her fingers and bring in a doula, for instance, to help her relax.

I would also love to see occupational and physical therapy consults offered to all mothers who’ve had c-sections, because it’s really hard to adjust to everyday activities after abdominal surgery, from picking something up off the floor to opening the dishwasher. Physical and occupational therapists can explain how to navigate these activities without further injuring yourself, can help you figure out how to breastfeed or comfortably position your baby for formula, how to change diapers when dealing with the pain of your incision. At the least we should be ensuring that one of these professionals sees c-section moms before they’re discharged from the hospital.

Last, changing the language that providers use to talk and write about C-sections is also important. Rather than calling an induction that doesn’t lead to vaginal birth a “failed induction,” or a VBAC that results in another c-section “failed,” we might explain why it’s time to move to the next level of intervention/care. Words matter. And even if no one says it to your face, seeing the words “failed” or “failure” on your medical records can really sting.

I know this is a tough one, so please do take it in whatever direction you’d like. If someone is anticipating birth, and wants to be a better advocate for themselves or a birthing parent particularly when it comes to pain and the potential for a c-section — what can they do, and what conversations can they have, ahead of time?

And if someone is grappling, as you did, with the aftermath of a traumatic birth or c-section — what do you wish you could’ve told your post-birth self?

I have a lot of ideas here. About pain in particular: I would spend some time reflecting about how you express pain, especially when you’re scared. Do you scream? Cry? Do you get really quiet?

I say this because one thing that played a role for me in my birth is that I’m a pretty stoic person. Even as a teenager I was like that. I fell when I was out snowboarding at 16, with my best friend, and when I sat up I said calmly that I’d broken it. The ski instructor was like, “If she’d broken her arm she’d be crying.” And my best friend, who knew me so well, said, “No, not Rachel. And if she says it’s broken, it’s broken.”

Labor was similar. I was in tremendous pain. I didn’t know it, but I was having back labor, which means that the baby’s spine was hitting mine. I also had continual contractions, one after another, without any respite. I remember thinking about the smiley and frownie faces on the pain scale for labor—you’re supposed to get to the frazzled frownie face when you’re 7 centimeters dilated, in transition. I was at frazzled frownie when I was dilated to a 2.

But I wasn’t crying or screaming. I don’t know if my pulse was high. I went into a really deep place inside myself. I closed my eyes. I couldn’t speak. If you didn’t know me, you might have thought I was meditating. Or, exaggerating, because I did say I was in a lot of pain, but no one really seemed to believe me. It was only when I was hooked up to the electronic fetal monitor that the people taking care of me said, “Those really ARE monster contractions.” You know — now that the computer confirms it, I guess you are right! Partly that’s because I’m a woman, which makes me an unreliable narrator, even about something as personal as my own body. But also the way that I expressed pain didn’t conform to what people might expect.

This insight about myself shapes how I navigate medical situations today, and I think can be useful for people anticipating birth. First, I tell providers, “I may look calm, but I’m really scared. I have significant medical trauma.” I would suggest people think about how they respond to pain and fear, and then do something similar during prenatal care, and even when they get to the hospital and meet the new people, like nurses or anesthesiologists, who will be taking care of them. “Hi, I am so-and-so. When I am afraid, I do X,” or “When I’m in pain I express it like this.”

Do not expect people to be able to read you if they don’t know you. And remember that your gender and/or your race may already put you at a disadvantage to being believed, so you may have to, unfortunately, even further course correct for that. I don’t say that to speak ill of providers, but that’s what the data tells us — this is the result of birthing in a racist system.

I also bring my husband with me now, usually, when I go to the doctor, which helps me to feel less scared. And, he re-articulates to providers — not in a patriarchal way — what I’ve said. “Hey, I just want to underscore that Rachel might look as though she’s OK, but she is scared — Rachel, am I getting this right?” That’s really helpful, because even when I am scared, I present as a calm person; call it a poker face or a strong container, that’s just who I am.

I would suggest that anyone expecting a baby discuss doing something similar with their support person: talk about how you express pain or fear, what you would want to be amplified, and how your partner or support person can do that in a way that feels right. Because having a baby is tremendous. It’s unreasonable to expect the person in labor, or about to have a surgical birth, can clearly articulate what she’s experiencing, especially to strangers. I’m not suggesting that women don’t know what’s happening in their bodies, by the way—just that you’re not really in the position to calmly and clearly communicate when you’re about to give birth. And, doctors are trained to talk to the patient, not the partner, which is appropriate — it’s your body. But/and, birth is different from knee surgery. You go into another plane of reality.

I’d also suggest exploring the difference, on your own and with your support person, between pain and suffering. Pain is something that you can get through: this contraction will end, I won’t have this pain forever. Suffering is bigger. It narrows your field of vision. You can’t concentrate. You can’t breathe through it. You can lose your moorings. If your pain turns into suffering, how can your providers or support person know that, and what do you want them to do to address it?

More broadly, I would reflect on what you’re hoping for from your birth, and think about how you might integrate that into a surgical birth or a vaginal birth. I don’t mean a birth plan, but what one OB described to me as thinking about “what is most important in your birth experience.” Maybe it’s that you want to be the first person to see your baby being born. Does that mean you want someone there with a mirror if it’s vaginal, or for providers to lower the drape or use a clear drape if it’s surgical? Likewise, I’d think about your fears, or what makes you uncomfortable, that can be part of birth in a hospital. Maybe it’s that you are uncomfortable being super-exposed — something that’s often part of having an operation. Can you talk to your providers about that in advance? What are ways that they can safely respect your desire for modesty while also inserting the catheter, for instance, in the OR? Or, while giving you a cervical check? (And do you even want those?)

I wish I could have told my post-birth self that what I’d been through was awful, that it would shape me in all kinds of ways, but that I would find my way back to my core self. That the way I felt when my daughter turned 1, 2, and 3 is not the way I’d feel when turned 7 or 8. And that I would come to a place, thanks to therapy and EMDR, that I could not only tolerate but love the kind of physical closeness that she craved when she was a newborn, but that at the time was too activating for me. That doing that therapy was the best and smartest investment I could have made for both of us, because we both deserve that intimacy. (Even now my daughter is like an oversized kitten who will happily sit on your lap all afternoon and read.)

And I would tell myself that I am a wonderful mother. ●

You can follow Rachel Somerstein on Instagram here & buy Invisible Labor here.

Caveat: I hate everything about this. And that's going to color so much of my response.

- No birth is trauma-free. Not a single one. Not even the very "best" ones where everything goes according to "plan" and everyone professes to feel healthy and well at the end.

- Every person's birth experience is valid, but it's also just ONE birth experience. Writing a book about your experience with your specific lens on the birth landscape is an effort in confirmation bias.

- Cesarean delivery, as practiced in the 21st century, saves lives. (That does not mean there aren't still providers in the world trying to get to a tee time. But in any major healthcare system, there is perpetual quality work being done trying to lower CS rates. That means more hospitalists (shift work - so no one has a tee time/is motivated by efficiency in birth) and more midwives (everyone should have a midwife!!! obstetricians are for when you risk out of midwifery care!)

- This book should have a companion piece about all the things you don't know about vaginal delivery. Like how your body might tear into your bladder and bowel and you might never void or defecate like you once did for the rest of your life. Or you might leak urine or stool or gas for the rest of your life. Or you might have pain with sex for the rest of your life. NO BIRTH IS TRAUMA-FREE.

Things that are absolutely correct:

- Every person should be able to take a full class about all the ways pregnancy and birth are going to FUCK YOU UP and change your life forever. This does not exist and if it did, fewer children would exist, because to know all the risks is terrifying. In a world of perfect reproductive justice, it would still be the norm.

- Unplanned cesarean deliveries are extremely difficult, especially if you read some of the modern books or soaked up the mantras that YOUR BODY CAN DO IT and YOU WERE MEANT FOR THIS MAMA - of course you feel like a failure, even if your body was NEVER going to push a baby out vaginally. We should be counseling every single birthing person that there are two methods of delivery, both are critical and valid and there is no value judgment between them. And you might need one in one pregnancy and another in another pregnancy and that is ok! And if that possible outcome is not acceptable to you, you should not have to participate in pregnancy and that's ok too!!!

- The history of medicine, including birth medicine, is racist. The people who choose to work in birth medicine are incredibly aware of that history and work daily to correct course.

For full disclosure, I had an elective cesarean delivery set to ABBA because I am A. posh, B. afraid of pain, C. anxious, and D. a urogynecologist. Recovery hurt, because it's major abdominal surgery. But my pelvic floor musculature is intact and that was MY birth goal. That and survival (which I almost didn't do - because as stated multiple times above, NO BIRTH IS TRAUMA-FREE).

I always try to find myself in people’s narratives about c-section births but so far I haven’t. I chose to have an elective c-section 9 months ago and it was the most affirming part of my journey to becoming a mother.

After three years of infertility, many uterine and fallopian tube procedures (sedated and not), hundreds of vaginal ultrasounds, uterine biopsies, egg retrievals, and many fertility healthcare staff saying, “it’ll be just a pinch,” the pain (physical and emotional) had compounded and I could not go through “natural” or assisted labor. I knew there was going to be nothing natural or magical about it because I had enough experience in women’s medical care to know “just a pinch” would be just that to a nurse but absolutely not to me. One of the OBs I saw during my pregnancy aptly called it, “a thousand little insults.”

So when I finally got pregnant and discussed my birth with my OB, the same person who diagnosed my infertility years before, I was so relieved at how open and affirming she was about an elective c-section. She said I was a good candidate and it could give me the peace of mind I craved after a long journey. I grappled with the decision because I worried what other people would think of me, most of all, what did I think of me???

Knowing I was going to get a c-section opened up such great conversations with my providers leading up to my birth, prepped my partner for those 5 weeks of his parental leave, helped my friends know what my birth would be like, and most of all, helped me manage my own expectations. My husband and searched for a post-partum doula to support us post c-section, too.

So all in all , what I’m saying is not necessarily that all c-sections are good ones, but that it is possible that a c-section is what’s good and nourishing to you!