This is the weekend edition of Culture Study — the newsletter from Anne Helen Petersen, which you can read about here. If you like it and want more like it in your inbox, consider subscribing.

The first time I saw Glennon Doyle speak, I knew she was on a rocketship out of Evangelical culture. This was back in 2016, just days before the election, and I was at the Bojangles Auditorium outside of Charlotte, North Carolina, for a stop on the BELONG tour. I had selected the event because Jen Hatmaker was going to be there — and in 2016, a lot of Evangelical women were trying to figure out how they felt about her.

For years, Hatmaker had been speaking at conferences like BELONG, which function as a sort of alcohol-free mom’s weekend that involves staying in a hotel together, doing some small group reflection, dressing cute, singing praise songs, doing a bit of journaling, and buying some merch. In Evangelical culture, men can be mega-church pastors, building their brands via sermons and didactic books, but women arrive at celebrity by documenting their family’s lives on Instagram, by authoring books that tred the line between self-help and bible study, and by speaking at women’s conferences, often about their “messy” family lives. But don’t call it preaching: it’s just sharing my story.

Hatmaker had been positioned as “the next Beth Moore,” which is basically like saying she was going to Evangelical Julia Roberts Meets Oprah. But then she said that she thought that gay people should be fully welcomed and included in the church, and all hell broke loose. Then she said it again — as in, yes, I really did mean this, the first time I said it — and Lifeway Christian Resources, the bookselling arm of the Southern Baptist Church, dropped all of her publications. (This was a big Evangelical deal, akin to all supermarket chains refusing to stock People Magazine).

Meanwhile, Hatmaker also started dropping hints that she wasn’t fully on board with Trump. The core of her celebrity seemed to be shifting, or at least challenging, some central assumptions of Evangelical culture: 1) vote for the Republican Presidential Candidate, and 2) gay people aren’t necessarily the devil anymore, but there’s definitely something wrong with them.

But at that point, just days before the election, Hatmaker’s charisma — the sheer wattage of love and compassionate that emanates from her — was enough to assuage any concerns amongst the attendees. They just loved Jen. Maybe they even agreed with her, even if they didn’t know how to say it quite yet.

As for Glennon Doyle — that was a bit more complicated. On the first night of the conference, Doyle gave a barnraiser of a talk in tight black skinny jeans and precarious heels. Back then, she was best known for her popular blog, Momastery, and her first book, Carry On, Warrior. But like Hatmaker, something was shifting with Doyle — both personally and in her image. She had only recently dropped the “Melton” from her last name, after divorcing her husband earlier that year, and her new book, Love Warrior, was about grappling with the disintegration of an ostensibly perfect family life. The book was chosen for Oprah’s Book Club. Whether or not it was carried by Lifeway Christian Ministries was already beyond the point.

Doyle’s talk that night was hilarious and defiant and raw— like she knew she had a captive audience of Evangelical women and wanted to see just how much she could push them and get away with it. Afterwards, one older woman, the sort that didn’t look like she’d gotten on board with the more Pinteresty components of Evangelical Culture, told me that she didn’t know if she’d be coming back to the conference next year. These events have changed a lot, she told me, they used to be much more like a bible study.

A week after that event, Doyle announced that she was in a relationship with soccer star Abby Wambach; six months later, the two were married. These days, Doyle has 1.5 million Instagram followers, and her latest book, Untamed, has sold over a million copies, and has been optioned by J.J. Abrams’ production company, Bad Robot, for a television adaptation. She chats with Gwyneth Paltrow. Adele loves her. And she’s off the Christian women’s speaking circuit. This sort of event, with Luvvie Ajayi Jones, is much more her speed.

As we would’ve put it back when I was a youth group addicted kid, Doyle “went secular.” But it’s more complicated than that. Doyle is still Christian — and if you heard her back in November 2016, or had been reading her before that time, you’ll recognize that the story and aesthetics of her Christianity hasn’t really changed. Her Jesus has always been a fairly radical one; Doyle herself has just become more adept at channeling her interpretation of his love in memes.

As young followers of Christ, my peers and I were often instructed to live in the world — as in, not separate ourselves entirely — but not be of the world. In practice, this meant that you could still go to public high school, and listening to the radio was probably okay, but it’s better if your CDs are all Christian. I was Presbyterian with a twist of Evangelical, so we were a little less hard-line about all this stuff, but I know that straight-up Evangelicals had stricter understandings about what was and wasn’t secular, and had internalized the imperative to shun artists like Amy Grant who’d crossed the line and, like Hatmaker, become too “of this world.”

But, at least at that point in the ‘90s, Democrats weren’t yet “secular.”

For much of the 20th century, where you lived, whether you attended a religious institution and what type of institution, even your race was not a reliable predictor of political affiliation. Lots of rural people were Democrats; same for religious people. This was certainly true in my small hometown in Idaho, where my church was filled with Democrats and Republicans, including a longtime Democrat state representative.

But that church began its rightward turn in the mid-2000s, and that Democrat lost his re-election campaign in 2016 to a far-right ideologue. I think it’d be very difficult to understand yourself as a Democrat and attend that church today without a ton of cognitive dissonance.

Which isn’t to say that Democrats don’t attend church: they do, including our current president. But most Americans have gravitated towards what political scientists call “mega-identities,” in which components of our identity overlap and incline us towards a particular political party. Apart from Native American reservations, which still swing overwhelmingly towards Democrats, rural residents are far more likely to be conservative; the inverse is true if you live in a city. Black Christians are still far more likely to be Democrats, but the vast majority of white Christians are aligned with the GOP. This all seems standard to us now, but again, it’s a pretty recent phenomena.

There are a lot of reasons for this shift — I strongly recommend Liliana Mason’s Uncivil Agreement: How Politics Became Our Identity if you’re interested in reading more. Some of it has to do with the GOP’s adoption of abortion as a central plank to its platform; some of it has to do with generalized union busting. But for this piece, I’m most interested in what this alignment has done to the values associated with the Christian church, purposefully or not. As the church became more closely aligned with the GOP and its values, it has increasingly understood itself in opposition to the Democratic party and its values. GOP arguments, behaviors, and ideologies have been sanctified, while Democratic arguments, behaviors, and ideologies are conceived as a “secular” or un-Christian in some way, even when the politicians behind them, like recently elected Senator Raphael Warnock, are actual Reverends.

Doyle has “gone secular,” then, in part because anti-racism, intersectional feminism, and LGBT+ inclusion are conceived of as secular values. Same with assistance for the poor, universal healthcare, even science or mask-wearing — they have to be conceived of as in opposition to Christian values in order for the logic to hold. What the gospel does or does not teach about any of these policies ultimately matters far less than the fact that they are aligned with Democrats.

This posture, however, has its problems. If being anti-racist is secular, then….what does it mean to be, uh, anti-secular? If supporting a Democrat is secular….who do you necessarily end up supporting instead? If you can’t support LGBT+ people and be Evangelical, who’s left in your fold?

More and more people are leaving established religions not because of the actual state of their faith, but because they cannot square their personal belief systems with the ideological alignments of the church. This is certainly true for me, and I know it is true for many others in my life who have left the church over the last twenty years. My problem with the church doesn’t really have much to do with God. I don’t think God is a racist, sexist bigot. But the church sure can be.

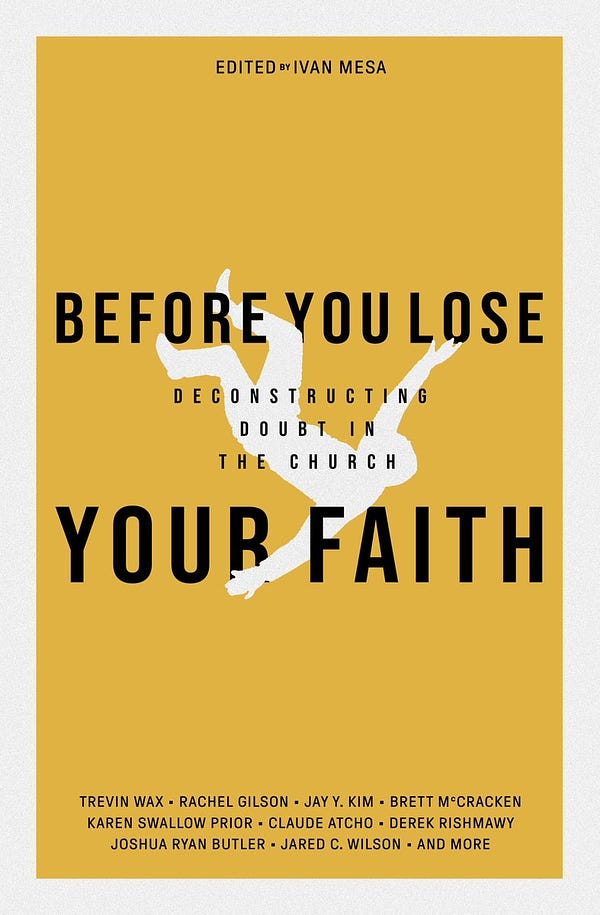

Some churches are trying to head off this sort of attrition by calling it “doubt” or “deconstructing.” They’ve created texts, like the one below, intended to shepherd members back to belief:

But as Blake Chastain, host of the Exvangelical podcast, points out:

“Deconstruction leads to many places, and often it doesn’t lead back to an institutional church or organized religion. I’ve been thinking a lot about how podcasts, social media, and other online communities have created new opportunities for spiritual and religious exploration beyond the control of “traditional” churches, and I think that white evangelical churches and organizations are particularly sensitive to their loss of hegemony.”

The church’s need to exclude certain objects and beliefs — from Harry Potter and Jen Hatmaker to LGBT+ Inclusion and Women Pastors — has always been a reactionary attempt to shore up that hegemony. It’s never really about theology. It’s always about power, and abject fear of its dilution.

Which is precisely why Doyle is a threat. She describes her following as a movement — ignited by women “in a collective moment of reckoning”: “We are looking at existing models of marriage, parenthood, religion, business, sexuality, and politics — and deciding that it’s time to let the old burn and imagine truer, more beautiful lives for ourselves, and a more equitable world for all of us.”

It’s clear, isn’t it? They’re deconstructing. But the work they’re doing, the ideologies of white supremacy and patriarchy and colonialism and heteronormativity that are becoming ever more visible and resistible in the process, it doesn’t lead them to the church, at least not in its current form. It leads them away from the church. It has to.

There are churches that are actively positioning themselves at the end of that road. People are seeking these sorts of congregations — but they’re also incredibly wary. Of anything manipulative, of anything that shuts down questioning, of fog machines and lifted hands.

And some are wary of Doyle, too — fearful that she’s the Instagram version of televangelist, with screenshots of tweets and mantras broadcast to an audience of millions, preaching a gospel that asks for little sacrifice on the part of its believers. But many of the people who follow Doyle, who’ve devoured her book and admire her, do want something more. They want to continue to deconstruct, as Doyle has taught them to do, and to be in fellowship with others who are doing the same. They want to challenge their biases, their privileges, their assumptions, their blind spots, even when it’s hard, and even when they fail. They want to “do hard things,” as one of Doyle’s sayings goes, and continue to show up for each other and for others.

They want, in short, to be better people. But they have no time for a group rooted in exclusion, and hate, and control. So if not the church…what else?

Earlier this week, Casper ter Kuile told me about a divinity school classmate of his who used to say “we all believe in something — it’s just we don’t always know exactly what.” As religion has failed to be the primary “distribution service,” as Ter Kuile put it, of that thing, people are looking all over the place for their religious content and community. Podcast groups of Facebook that discuss a lot of things that aren’t the podcast? Sure. Peloton? Of course. Twitter? There, too, with diminishing returns.

I think the natural inclination is to think of these sites as shallow, empty, superficial — and many can be that. But just like a youth group volleyball tournament is secretly a way to get kids to talk about Jesus, this sort of fellowship can lead to intimacy, which provides the necessary trust to ask and attempt to answer much bigger questions about who we are and the lives we lead. I’ve certainly found this to be true on the subscriber threads here, and it’s at the heart of what people yearn for when they yearn for the Old Internet, too. Intimacy and community, but also challenge and interrogation and growth.

After the pandemic, these online communities will continue to grow. But I also think we’re going to see a real explosion of in-person, formalized, goal- or ideologically-oriented gathering as well. We’re going to join things, commit to things, volunteer for things, and begin — I think! — to rebuild a civic foundation. Maybe not on the scale of the post-war period, when the collectivist ethos was at an all-time high. But we’ve seen the alternative, and that shit is just overwork and rugged bullshit individualism and darkness.

People are hungry to be with each other in a purely social sense, but they’re also searching for clarity, purpose, strength, and care — the sort of thing many used to get from the church. Either churches can try and do what St. Jax, in Montreal, Canada, is doing, and reimagine themselves and their mission at the center of the community, or they can retrench themselves in bitterness, revel in self-righteousness, and watch their congregations dwindle. We will gather and seek meaning and fellowship in the world. It just won’t be there.

Things I Read and Loved This Week:

The Zillow maps that inadvertently show the traces of “ghost neighborhoods” displaced by urban renewal

One of the best summaries of all that’s wrong in higher ed right now in the form of a resignation with a stomach punch of a kicker

Daycare makes the world more tender

Nicole’s answer here to a reader question about dealing with a child who’s been bullying an Asian kid at school is worth your time, regardless of whether you have kids

We're so obsessed with means testing and short-term thinking in the U.S. that we can't see the solutions right in front of our eyes

This week’s just trust me

If you read this newsletter and value it, consider going to the paid version. One of the perks = weirdly fun/interesting/generative discussion threads, just for subscribers, every week. This week’s Friday Thread was a Meta-Thread on future topics; I can’t explain how it arrived at such an interesting and weird place but it certainly did.

If you are a contingent worker or un- or under-employed, just email and I’ll give you a free subscription, no questions asked. If you’d like to underwrite one of those subscriptions, you can donate one here.

If you’re reading this in your inbox, you can find a shareable version online here. You can follow me on Twitter here, and Instagram here. Feel free to comment below — and you can always reach me at annehelenpetersen@gmail.com.

The major stumbling block for so many of these institutions is the failure to truly grapple with and atone for the abuse of children and come up with structures that would ensure accountability going forward. At a root level, how does one trust his or her children to a church that put the institution before a child’s well-being? How do you engage with that institution as a family? I grieve so much for what the Catholic Church took from me & my relationship with God and I was not victimized. I know that story is not unique to Catholicism. I had found a new Episcopal church in early 2020 but it didn’t feel like home.

And this is why we love Culture Study 😘👌🏾