Ask yourself: apart from family, how many close friends do you have?

You can define “close” however seems appropriate to you. For example: I have close friends who live near me and close friends who don’t. A close friend can be someone you’ve never actually met in person but talk to constantly…or someone you might not talk to every day or every week but nonetheless understand your relationship to them as “close.”

Now that you have an approximate number, think about how that number has changed as you’ve aged. How many close friends did you have in high school? In your 20s? In your 30s or 40s?

I always thought that as you moved through life you’d just keep accumulating friends, layering new relationships onto existing ones. But looking at new data from the Pew Research Center on the state of friendship in the U.S., I’m reminded of my own surprise when I woke up in my mid-30s and wondered: do I still have friends?

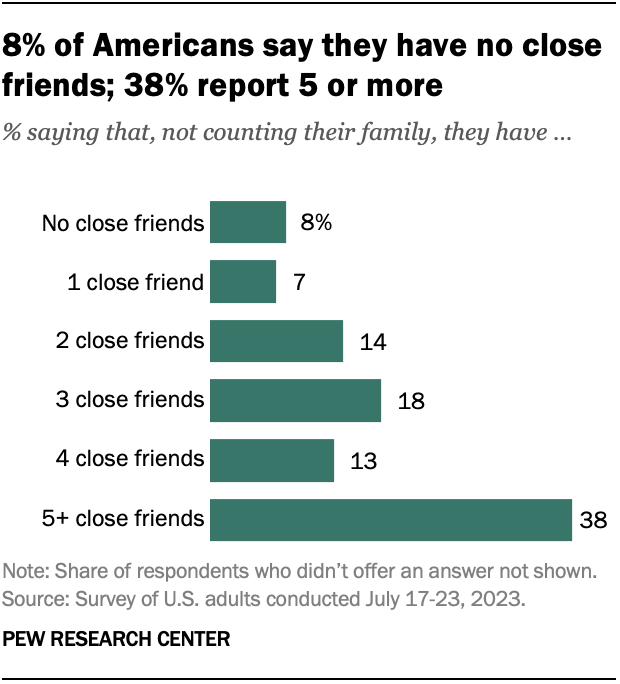

Here’s what Pew found. A whopping 38% of Americans say they have five or more close friends. 55% say they have between one and four close friends. And 8% say they have no close friends.

That’s interesting, sure. But I was more compelled by a secondary stat: 49% of adults 65 and older say they have five or more close friends. That number just keeps going down as you go down the age range: 40% of those 50-64 have five or more close friends, compared to 34% of those 30-49 and 32% of those younger than 30.

Pew didn’t survey anyone under 18 for this particular survey, but back in 2018, they found that 98% of teens say they have one or more close friends, 78% said they had between one and five close friends, and 20% had six or more close friends (2% said they did not have any close friends).

When I was in high school, I would’ve said I had at least ten close friends. I also know that the high school experience has changed since 2018. But here’s the general trajectory I’ve observed/synthesized/come to understand:

Young Adult: Solid Number of Close Friends

Early 20s: Still lots of Close Friends, many of them the same as the ones from high school/college, but add in work friends/grad school friends and subtract friends who move away/lose touch.

Late 20s/Early 30s: Complex machinations around friendship as many people move from group living arrangements to couple living arrangements and designations of “close friendship” are solidified or challenged by wedding / wedding party invites (who amongst us has not been surprised by being invited/not being invited to be part of a wedding or attend a wedding).

As the amount of quality time decreases, the number of friendship “spectacles” (weddings, but also group trips with matching t-shirts) increases, as if to reassure yourself and others of the endurance of your friendships as societal forces/structures begin to degrade them.

30s: Pretty massive schisms in existing friend groups as kids enter the picture, new and tenuous friendships form around daycare and schools, lots of spoken and unspoken resentment around schedules and availability and expectations, class differences playing out in ways that are more difficult to ignore, housing/schooling decisions that create scenarios where you can live within 15 miles of someone and see them once a year, while calendar culture turns a bunch of friendships into group texts. Some people lean hard into careers/advancement and others take a step back. Just lots of diverging paths in the friendship woods.

Late 30s/40s/The Portal: Reckoning with the state of friendship, attempting to rekindle ones that have gone fallow or let go of ones that feel toxic, a little more time and space to figure out how to show up for existing friendships. A bunch seismic events (big losses, aging parents, divorces, illnesses) that challenge and clarify friendships….but still just not a ton of time/space for cultivating new ones. It’s more like: this is the time to figure out how to cherish and prioritize your existing ones.

I haven’t reached my 50s and 60s yet, but from what I’ve observed: Even more reprioritization, some moving/reorienting life around grandkids, plus splits between people whose time is still absorbed by their (adult) children and those whose time is not, for whatever reason. Some more porous divides between those who’ve begun to transition into a more retired lifestyle (snowbirding, slowing down at work) and those still very much working full time, plus difficulty making space for friendship when absorbed in care for one’s own aging parents (or grappling with debilitating illness).

Mid-60s and Beyond: Retired or nearly so and lots of time to mold to your whims — starting new hobbies or rekindling old ones, volunteering on a regular basis, being a person who can show up and help out (for your own family, but also for the community). More time to visit. More time to walk. More time to help out. More time for illness support groups and driving others to the doctor. More time for your family, sure, but more time for your peers — particularly if you live in a place with a bunch of your peers in close proximity, whether a retirement community or just a neighborhood with other retired-ish people.

There’s that group of people — the people over 60 whose social calendars feel busier than mine ever has been — but there are also people over 60 who don’t live in places that are conducive to community, or who just don’t like showing up to things and don’t have established relationships to tie them to others. Maybe their health or disabilities make it hard. Maybe there’s just no reliable transportation. Maybe a whole lot of factors have conspired to cut them off from companionship. When people talk about loneliness aging you, that’s who they’re talking about.

Over time, your friends begin to die. Or you die. That’s just how aging works. But I also know that at some point, exact age ceases to matter. You’re either a person with time and energy for friends and community or you’re not. You’re a person with a somewhat malleable schedule or you’re not. You’re a person who has so many priorities in front of friends or you’re not.

I know there are exceptions to these binaries, and I also know where we land is often not wholly within our control. These aren’t meant to be judgmental descriptions, just descriptive ones. And I think it’s important to emphasize that right now, the way our society is organized, we have a prolonged stretch of adulthood that is not conducive to forging or sustaining friendship or community. In many cases, I’d say it’s actually hostile to it.

I call this period the The Friendship Dip. And I think it makes a lot of us miserable. First in our late 20s and 30s, when we don’t really have a name for what’s happening but can nevertheless feel it….and then in our late 30s, 40s, and 50s, as the extent of the wreckage becomes clear and we attempt to rebuild.

The biggest problem, of course, is work — and not just normal work, but all-consuming work, slippery work, work that becomes the central axis of our lives, either out of necessity or compulsion. But the secondary problem is American individualism, which compels bourgeois Americans to focus what small amount of energy we have either on optimizing ourselves (exercise, skin care, “self-care”) or on our very close familial circle (that amorphous, ever-expanding activity known as “parenting” that includes everything from making Spirit Week costumes to kids’ sports).

Many of us currently grappling with The Friendship Dip work the way we do because we’ve been conditioned to precarity — and many parents, particularly white bourgeois parents, parent the way they do because they’re anxious about downward mobility. I get it. But if we want to have more close friends — and more community — we have to figure out how to behave even slightly more like our boomer and silent generation elders.

Now, I can already hear the pushback: I’d have more friends too if I had a pension and a bunch of home equity. But the truth is that the median boomer has just $266,400 in wealth — and for most, that has to last several years if not decades into the future. Time for friends is a privilege but it’s also a matter of priorities. Also, let’s be real: amongst your friends, is there any correlation between the people with the most wealth and the people with the most time for friends? No! We used to be a society where the wealthy did not toil, but now we are a society where the more money you make, the longer hours you work.

My theory is that retirees have more time, sure, but they’re also just generally more practiced at the infrastructure of community and friendship. They’re not the peak “joiners” that their parents were in the post-war period, but they grew up in households that were much more likely to have strong connections to religious and community organizations in some capacity. (If you’re interested in these shifts, I recommend Robert Putnam’s classic Bowling Alone and its “sequel,” The Upswing).

For these generations, being a part of something (or multiple somethings) that were not work or school — a women’s league, Rotary, gardening club — was much more normalized. They may have strayed from that norm at some point during their adulthood, but they have the muscle memory of showing up, helping out, and spending time visiting about nothing and everything.

As Barbara Ehrenreich and Katherine Newman have convincingly argued, many boomers also had anxiety about falling out of the middle class in their 30s and 40s. But those years of their lives were not subject to constant optimization. The kernels of productivity culture had been sewn, but they hadn’t yet been normalized. Some upper middle-class white boomers were parenting in the style that’s become known as “concerted cultivation,” but most parents were not (across classes and genders, parents today spend significantly more time with their kids than their parents and grandparents did).

My boomer parents had a lot of close friends. Some of that had to do with their personalities, but some of it had to do with the existing social infrastructure of our town and the rhythms of life. My mom was part of the PEO, which, as far as I could tell, was basically ladies sitting around chatting with a bunch of baked goods and giving out scholarships. Both parents played adult league soccer. There were fishing trips and camping trips and a lot of time just hanging out on the silty beaches of the river, eating Albertson’s Fried Chicken. We spent so much time at stuff related to church: choir rehearsals, cook-outs, trips to the waterslide. I played piano and took very low key dance classes and begrudgingly played soccer but my family’s schedule never even came close to rotating around my calendar.

My friends’ parents were part of other things: the community theater, 4-H, other churches, the Elks. In hindsight, I’m sure that some of it could feel cliquey and exclusionary, but what I absorbed was that 1) my parents had social lives, and sometimes those social lives complimented my own (the blessed dinner party that included parents of friends my age) and sometimes they trumped them; 2) sometimes being a part of something meant just showing up every week and doing semi-boring stuff, like setting out the cookies before coffee hour.

If I was born ten years later — or if I grew up in a different place with higher-stakes college admissions competition — I think the community rhythms of my life would’ve been very different. Instead, I had a loose blueprint that sustained me through college, that I struggled to maintain through my own 30s and 40s, and that now, as part of my own experience going through the portal, I’m returning to in my 40s.

I don’t always beat my most anxious, introverted, and optimization-minded tendencies. But I’m getting better. At going to coffee klatch and just visiting. At reminding myself that not working for 90 minutes on Thursday afternoon and instead picking up my friend’s kid from school and talking about Harry Potter will not doom my entire day. I hope I’m modeling something for those kids — in my close friendship with their parents and my ongoing presence in their lives, but also just by being a person who they see at community events, a person who shows up. And, importantly, not just for them.

The Friendship Dip makes everything harder. It’s lonely; it’s alienating; it’s confusing. It shouldn’t be this hard to balance the maxims of adult life. But I also fear that with each generation, the dip is not only widening to include younger and younger adults and kids, but also becoming ever more insurmountable. I had memories to revive. But kids today — what do they see, and what are they learning, from the way we’ve arranged our lives? ●

For discussion today, I’d like to hear your thoughts on where you find yourself in The Friendship Dip. How have you made it easier for friendship and community to co-mingle with the rest of your life? What would you like to change to make that happen? And for older readers, I’d especially love to hear how friendship and community is working for you. What’s hard, and what’s easy? What did I miss?

Subscribing gives you access to the weekly discussion threads, which are so weirdly addictive, moving, and soothing. It’s also how you’ll get the Weekly Subscriber-Only Things I’ve Read and Loved Round-Up, including the Just Trust Me. Plus it’s a very simple way to show that you value the work that goes into creating this newsletter every week.

As always, if you are a contingent worker or un- or under-employed, just email and I’ll give you a free subscription, no questions asked. (I process these in chunks, so if you’ve emailed recently I promise it’ll come through soon). If you’d like to underwrite one of those subscriptions, you can donate one here.

If you’re reading this in your inbox, you can find a shareable version online here. You can follow me on Instagram here — and you can always reach me at annehelenpetersen@gmail.com.

Oh man, I struggled with friendships all through my teen years and 20s! I would have said I had fewer than 3 close friends at any point during those decades. I couldn't say why that was -- some combination of being socially awkward, a late bloomer, whatever -- but high school, undergrad, and graduate school were not halcyon days of friendship for me, heh.

I had a brief "golden age" of friendships in my early thirties, newly out of grad school and into a professional job, in a happy relationship. I organized a number of well-attended weekly and monthly and seasonal gatherings with friends, and it all felt so wonderful... until almost all of those friends started having kids and stopped prioritizing these gatherings, and I entered the long, dark years of infertility. But what emerged from that was a concerted attempt at cultivating friendship with people who could meet me where I was AND who became my role models for how I want to live with the cards I've been dealt. A few of my parent friends became that, but so did many, many new friends -- most of them older, and/or queer, and/or out of step with the "usual" life trajectories and expectations in some way.

This resonates so much: "You’re either a person with time and energy for friends and community or you’re not. You’re a person with a somewhat malleable schedule or you’re not. You’re a person who has so many priorities in front of friends or you’re not." To that, I'd add, you're either a person who can be comfortable with the emotional vulnerability and risk of building and maintaining close friendships, or you're not. There have been times in my life when I didn't have that capacity, and times when I did.

Building and maintaining friendships is such a confluence of luck, prioritizing, skill (which I did NOT have in high school or in my 20s, not really), and what I'd call emotional availability, and it's amazing to me that I have as many friends as I do! I have more, and deeper, friendships now in my 40s than I ever have before.

Infrastructure is an under-appreciated factor here. danah boyd’s research with teens emphasized how loneliness starts to get built in when friendships are conducted online (when not in school) not out of choice but because kids can’t walk or bike to meet with friends and are dependent on their parents for rides. How much friendship-building and -maintaining skill gets lost in those years simply due to a physically isolating world?