This is the midweek edition of Culture Study — the newsletter from Anne Helen Petersen, which you can read about here. If you like it and want more like it in your inbox, consider subscribing.

I’m not a mom but I like to know what the moms are up to. You should too, regardless of your identity, because “the moms” — meaning, the moms embodying and directing ideals of femininity and domesticity and parenting — have a lot of power, and power demands attention. I follow some of these moms on Instagram: there’s BallerinaFarm, a mix of a trad-wife + Miss Utah + Juilliard ballerina, pictured above with her six children on their farm (what you don’t see: her husband, whose father founded JetBlue!) and McKinli Hatch, the mother of four who’s parlayed viral chalkboard baby name fame/infamy into a clothing line, divorced her husband, and let’s just say leaning into a second act, and TurtleCreekLane, a Dallas mother of five with self-described “over-the-top decorations.”

There’s a lot going on in all of these accounts! They are rich ideological texts of whiteness and domesticity! I can and do go down deep rabbitholes when I find a new one, the same way I have with the Baylor Influencer Twins. But I don’t know momfluencers like Kathryn Jezer-Morton.

Jezer-Morton is currently writing her dissertation on these accounts and the women behind them at Concordia University in Montreal. She started her Master’s degree after having her second child, when she realized that 1) writing for lifestyle media was not sustainable but 2) she still wanted to be a writer and researcher, and a PhD would help her figure out how to develop an expertise in something she very much wanted to write about. She’s worked full-time through the process and doesn’t plan to look for a job in academia, but the space of the dissertation has allowed her something we rarely see in writing about internet celebrity: extended space to trace a trend, like moms making space on the internet, as it’s happening. She’s been watching these developments closely, with the tools of a researcher, for nearly a decade — and I really think it comes through in her work, which is so layered, with the sort of ease and detail that makes it irresistible.

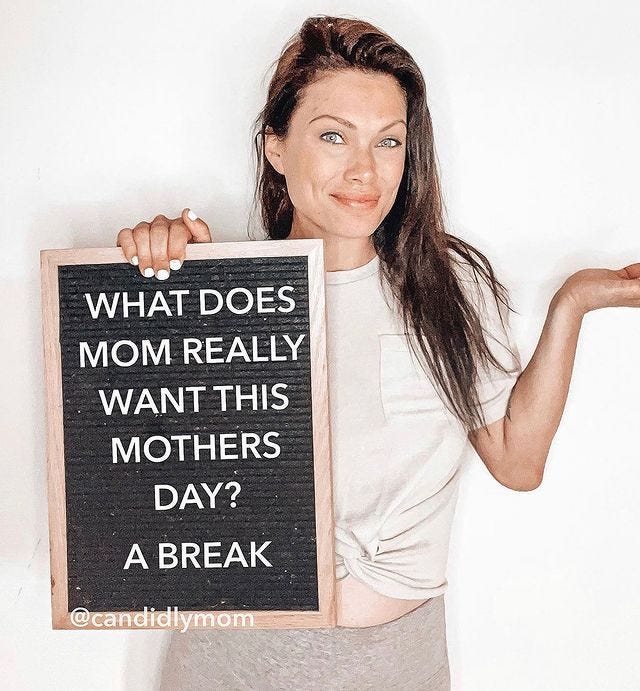

She’s also a rage-inducingly good writer. I genuinely laugh out loud every time I read her while also wanting to throw the computer because I’m jealous of a turn of phrase or insight. Take this paragraph, from her recent tour de force on letter boards:

Letterboards used to be associated with brick-and-mortar businesses. They were used for posting the menu, or business hours. There’s something queasily on-the-nose that might be hitting some of us subliminally about an artifact of small businesses being appropriated by moms as they try to frame their home lives within the boundaries of what’s marketable on Instagram. I mean.

It can be hard to square the fact that motherhood, which is like the biological inverse of commodification, has been fully commodified by momfluencers. But ma’am, this is an Arby’s. Instagram is a platform with massive, throbbing biases and it can make you rich if you work (extremely) hard at it. And you expect moms, in this economy, to not participate?

I think you’ll find Kathryn’s take on momfluencers as compelling as I do — and if you want more, I strongly suggest subscribing to her monthly newsletter, which you can do here. (She also wrote this wonderful piece about growing up in a commune in Vermont, which I wrote about here. She is also the only person, outside of my former students, who understands what I mean when I talk about the glory of the Putney Co-Op. Kathryn! She’s the best. I love it when she talks about Québécois particularities. You should follow her).

You wrote a piece for the Times last year in which the headline somewhat cheekily asks: “Did moms exist before social media?” They did, of course, and you immediately acknowledge as much, but can you talk about what we’re talking about today when we talk about motherhood — and how you became interested?

Over the last 15 years, social media is where so many norms about what it means to be a “good” mother have been renegotiated. That’s really why I decided to study online motherhood -- it felt like the place where everything was happening. Online motherhood in North America today is a wildly contested space. It’s an ideological battleground, located inside a Target. You’ve got people debating vaccination, breastfeeding, sleep-training, nutrition, gender. And then you have the politics of domestic life, the female body, white supremacy, consumer culture, labour... All these discourses play out in the “mamasphere,” as academics refer to the internet-of-moms. And the people setting the tone in the mamasphere are momfluencers, so whether or not they choose to acknowledge it, they are bellwethers. People seem to care what momfluencers have to say, sometimes as much as, or even more than, political pundits. I think that has something to do with this residual feeling that motherhood is a sacred space. So what momfluencers say sometimes really carries weight.

I got interested in online motherhood when I had my first son, in 2010. I loved the early mommyblogs — the storytelling, the real-talk, I just ate it all up. Then when Instagram became popular in 2012, online motherhood started to look different: more polished, more sales-oriented. Motherhood had fully matured into a social media marketplace. I should add that I totally understood what the early mommybloggers were up to, how their lives worked, but when it became image-based with Instagram I felt like the wheels came off my comprehension. I was in a state of total bewilderment. The influential moms on Instagram made me feel like David Byrne from the Talking Heads, moving through my environment in a perpetual state of confusion. “What’s happening here? What are they doing in those pictures? Who’s TAKING the pictures?” So I decided to get my PhD and try to figure it out.

The mediation / representation of motherhood is not new, not at all. The sheer number of articles I read in the 1930s and ‘40s fan magazines “written by” a star about their own experience of (perfect) motherhood! The mind is boggled! So I’d love to hear anything you have to say about how often motherhood gets dehistoricized or, like, improperly historicized, as in “This is just what moms do, it’s what moms have always done,” etc etc.

Instagram is pure PR for the nuclear family, and it totally erases how much childcare has always been shared within communities — and how much families have always relied on each other to raise their kids. Because Instagram is just images, and momfluencers try to have everyone camera-ready for posts, and those posts need to be very easy to “read” while you’re scrolling (here’s the family toasting marshmallows, here they are at the beach, here they are all together in PJs) it’s just easier to control the imagery if it includes only the nuclear family.

Like, you’re not going to ask your neighbour Janine who looks after the kids twice a week to put her hair in barrel curls so she can appear polished in a picture, you know? Also, no one’s going to read a caption explaining who some random person in the pic is. The audience is tuning in for the main characters. The upshot is that we see a completely ahistorical representation of family life in most of the mamasphere. Care-work is completely erased. There are no neighbours in the mamasphere! Back in the day, Ree Drummond used to post sometimes about her neighbour Hyacinth. Shout out to Hyacinth, I always liked to see her in the mix.

I will say this: there is more representation of fostering these days (Ree’s in there again in that regard, and most foster kids have to remain out of photos, but you’ll see them referred to anonymously sometimes), and of blended families. But the nuclear family remains the monocrop.

I want to hear about the scope of your dissertation — how has its form changed with time, how have you decided to organize it, what writing and theory has informed it, how did you find the bloggers and influencers you wanted to study….please tell us everything.

I started my PhD five years ago, so momfluencing has evolved a lot in that time and I’ve gotten to try to keep track of the changes. I started out by trying to wrap my head around the tension between two related questions: how are momfluencers acting as vectors of neoliberal discipline and control, but also simultaneously creating their own tactics and strategies for survival within a precarious economic environment? A bit of interplay between Foucault and Bourdieu. But when I started thinking about actually designing a research project, I knew I had to zero in on specific practices and move away from these giant questions.

I started thinking about expertise and momfluencers. Throughout the 20th century, there were “experts” in the media who told mothers how to do everything. But social media had the effect of diffusing expertise (and then of course we have the rise of misinformation). So, what kind of expertise do momfluencers cultivate?

Two books in particular helped me think a little more carefully about this: Mothering Through Precarity by Julie Wilson and Emily Chivers Yochim, and The Juggling Mother by Amanda Watson. Mothering Through Precarity situated mamasphere discourse in the context of the neoliberal precariousness of many mothers’ lives. The mamasphere’s audience is consuming this media as a balm, an escape. A lot of how the mamapshere’s tone and imagery has evolved in relation to that need for escape. Momfluencers get criticized for presenting these polished facades, but to a great extent, that’s what audiences enjoy. So momfluencer expertise might be partly a matter of making life look fun, easy and beautiful.

In The Juggling Mother, Watson writes about how contemporary motherhood and the media made about it are defined by this state of being overburdened, of having an impossible amount of labour to juggle. Having too much going on, but pulling it all off with a smile — Watson calls this the “exalted state” of white privileged motherhood. There’s even a particular way to “come apart,” to struggle under the weight, that’s part of this social script of exalted motherhood, and it’s only available to upper class white women. Coming apart can be very high-risk for women of colour and working-class women: we see this when a Black woman is arrested for leaving her child in a park while she attends a job interview, for example.

To Watson, these acts of bearing up under too much responsibility and coming undone according to particular social scripts are some of the “affective duties” of contemporary motherhood: the ways we feel we should organize our emotions. Watson’s book nudged me into the wonderful world of affect theory - which deals with, among other things, the subtle “processes of orientation” (those are Watson’s words), that direct us. I began to notice the way that these affective duties play out among momfluencers. There’s a way to create content, a way to represent oneself, that fulfills your duties as a highly successful, overburdened-but-loving-it supermom, but that also brings in these precarious moms in the audience, that doesn’t alienate them. How do momfluencers undertake that labour? What considerations go into making that content? To me, answering those questions can teach us something important about the impact momfluencers are having on contemporary motherhood.

That’s when I started thinking through a theory of “affective expertise,” which was a label suggested by my extremely patient thesis supervisor, Bart Simon. Theorizing affective expertise among momfluencers has become my main thesis topic. How do momfluencers modulate their posts to be “relatable” while still fulfilling their affective duties as “successful” moms? The starting point to answering this question is basically asking moms, “How do you decide what to post?” and then asking “why?” in as many different ways as possible. There are usually so many considerations that go into making a post, and it’s in those considerations that I locate affective expertise.

In interviews, I was hearing a lot of speculation about Instagram’s algorithm, and the type of content it rewards, and “shadowbans,” and what gets you on the Explore page. This is of huge concern to momfluencers who often feel like their success or failure is determined by what the algorithm likes, and the algorithm is always changing unexpectedly. (Brooke Erin Duffy, who works at Cornell, is essential reading on gender and digital labour, and this precise condition of algorithmic precarity. Her work is central to my research.)

I’ve learned that a lot of moms are increasingly planning their content around what the algo rewards. It brings to mind actor-network theory -- the idea that the mamasphere is a series of interactions between human and non-human actors. Time to read more Donna Haraway! The algorithm is absolutely an actor here. Momfluencers have to try to decipher its preferences and react accordingly. Which is part of why sometimes everyone in the mamasphere appears to be doing exactly the same thing, like a bunch of tall-boot-wearing synchronized swimmers. Like using letterboards, for example. They are doing something that they have found to be effective for the success of their accounts, but probably won’t be effective for long.

So what if affective expertise is also a matter of intervening strategically in this entanglement with a non-human actor (the IG algorithm) and adding some human agency into the mix? I’m beginning to wonder if the most successful momfluencers are the ones that can ride that knife’s edge between pleasing the algorithm and appearing three-dimensionally human to the audience. And I’m learning that this is extremely difficult to pull off.

How do I find momfluencers to talk to? I do a lot of cold-emailing of moms whose accounts I have been following for years, and I always ask them who else I should interview. This works sometimes but I rarely get to chat with those women for more than an hour, because people are busy.

There’s an annual mompreneurship conference, Mom 2.0, that has gone virtual since the pandemic. I wanted to go for a few years before the pandemic but the expense of flying to LA or Miami and paying for the conference fee plus hotels was never really justifiable for me. Last year and this past month I attended virtually, and it’s a great place to observe momfluencers discussing their work with each other, and I have met a bunch of moms there who have become important sources for me.

I should add here that for most of my doctorate so far (except for one glorious six-month period), I have been working full-time. I stopped working on my dissertation during the pandemic, I simply could not muster any progress, and I’m just now returning to it full-steam… while also working. I guess my point is that my own experience is entangled with “too-muchness” and affective scripts. It’s an intimate topic.

What are your favorite motherhood blog tropes and how have they morphed as they’ve moved to IG? Bonus points if we get to talk about the letterboards, because this entire Q&A is just an excuse to talk about the letterboards.

The October edition of my newsletter is ALL about letterboards so I don’t want to spoil it! Subscribe to learn more — I explain them! The moms told me everything! The whole use of text within the image, letterboards and chalkboards and whatnot, might have peaked during the pandemic, I am sorry to report. Now it’s on to Reels and Tik Tok stuff, and I feel for these moms who now have to learn how to basically perform short skits. I mean, they did not sign up for this, but the platforms never stop changing.

My favorite tropes, oh boy. I am fascinated by momfluencers’ home interiors, the constant upgrading and renovating and reorganizing of nurseries and bedrooms and the requisite “reveals.” A few years ago Amber Fillerup Clark revealed her new laundry room and it contained TWO washing machines side by side and my soul temporarily left my body. Taza of Love Taza has a row of fridges with, if I am not mistaken, glass doors like a bodega beer fridge. I am riveted by this. Interiors were really not part of mommyblogs, but of course they are Instagram content mines. There does seem to be an interiors arms race, which mirrors the general pressure within capitalism to continuously “level up,” and when we bring that pressure into the home, it’s worth paying attention to what happens next. Also, kids grow up and sometimes don’t want to be photographed anymore, but interiors are always fair game. I think as momfluencers work to diversify their content in preparation for their children growing up — which is happening more and more, as the first big wave of momfluencers’ kids reach adolescence — we might see more emphasis on home decor.

I’m also into the evolution of posts about snacks for your kids. It used to be like, “My kids love Goldfish! Here they are eating goldfish in our light-filled kitchen.” Now you see moms staging enormous platters strewn with every kind of treat and calling them “charcuterie boards.” As a person living in a French-speaking place, this makes me shriek, because charcuterie does mean “meat,” not “snacks,” and I love — sincerely — the way momfluencers have appropriated the term.

Some charcuteries:

We talked last year for a story I wrote on QAnon and “save the children” and how the online influencer world was processing, for lack of a better word, Black Lives Matter. A year later, do you see ripples and ramifications in the way some of these white moms understand whiteness? Have others been radicalized (in either political direction)? And how do you anticipate momfluencers grappling with COVID vaccines for kids, and why does that matter?

There are some white moms whose brands have shifted since the murder of George Floyd in May 2020, and now you’ll see them acknowledging their white privilege in subtle and sometimes overt ways. That being said, I would be surprised to see the word “whiteness” anywhere near a momfluencer’s content. I think race continues to be hard for most white momfluencers to engage comfortably with on social media. The white mamasphere is a place where a fundamental ideology of white supremacy — that whiteness is raceless, and all other races are racialized — is still pretty much completely hegemonic. I think that for white momfluencers, talking about race is high-risk from the perspective of alienating followers… which is another way of saying that anti-Black racism is very entrenched among mainstream white women. So you have white momfluencers basically retreating from the topic of race on the grounds of “I can’t handle the fallout among my followers.”

You could think of the decision not to post about “controversial topics” as its own kind of algorithm, which then selects other topics to replace the controversial ones, and over time erases any trace of them.

Christian momfluencers are a huge swath of the white mamasphere (and Black mamasphere - although the two Christian populations rarely seem to overlap) and they tend to use coded language to appeal to conservatives without alienating liberals. Christian homeschooling content in the mamasphere is totally mainstream and I think that can be traced at least in part to the influence of the Trump presidency. There’s an appetite for rural retreatism both among Trump supporters and disillusioned liberals, so these momfluencers with six kids living on ranches appeal to both groups for different reasons.

I can’t wait to see how the vaccine will be dealt with among momfluencers. I think there’s a good chance that most of them simply won’t post about it. Women with huge followings didn’t tend to post about their own vaccination choices, so I assume they will maintain the same approach for their kids. To these women, posting about these hot issues is simply more trouble than it’s worth. You have to remember, it’s also a time-management issue. They know that if they post about something controversial, they will be tending to their feed for many extra hours, and this just might not seem worthwhile to them.

The first edition of your newsletter is about a mom influencer who really drew out the announcement of the gender/name of her fourth child. You assumed it was a means of boosting engagement — and I remember you tweeting about this, and I totally agreed with you. But then, because you have an established relationship with her from previous interviews….you just asked her what was going on? And her response was much more complicated (and much less, in some ways). I think there’s a real reticence to 1) ask people what they’re doing with their online performance and representation and 2) trust them to have any sort of objectivity (or even transparency or ‘honesty’) when it comes to describing their thought processes or motivations.

I get it, but I also think that it sometimes assumes that all of these moms are afflicted with some sort of false consciousness — it can feel really infantilizing, or misogynistic, or as so common with women in the public sphere, both. How do you think through these tensions in your own analysis? What’s lost when we don’t take momfluencers seriously?

Interviewing momfluencers has changed my perspective on their work completely. Without exception, the momfluencers I’ve spoken to are very deliberate in how they post, and they speak about it as work that they undertake strategically, as professionals. Representing motherhood puts you in a double-bind because audiences expect you to be “authentic” because you’re representing this foundational — even sacred — social relationship between mothers and children, but at the same time, you’re under enormous pressure both from brand partners and the audience to look a certain way. So to disparage them for having a false consciousness to me feels very dismissive.

I try to stick to my commitment as a researcher to listen to my informants and ask questions in good faith. I see these women as precarious labourers in a marketplace of creative and affective labour. Some momfluencers parlay their followings into launching successful businesses, but most don’t. They know it’s not a forever thing, and they’re trying to extract the most value from these platforms as possible, while they can. The other night my husband proposed the analogy that momfluencers aren’t that different from workers on oil rigs. Their resource is the attention economy rather than oil, and they’re exploiting that resource. At the time I laughed at him but the analogy has stuck in my head.

But there are definitely tensions in analyzing momfluencers as producers of visual culture. Their work is not neutral: it has social consequences. Looking at the most of the imagery in the mamasphere from the perspective of an intersectional feminist, I mean where to begin? But blaming momfluencers for perpetuating patriarchal power structures, to me, feels much too reductive. I don’t see that as part of my work because it’s not a reflection of my research findings so far. The algorithms are reinforcing certain types of content over others, and moms are building their strategies based on the algorithms — they are constantly trying to figure out what the algorithm wants to see. I’m not saying they are not responsible for the content they produce, but I think it’s important to acknowledge the iterative process through which content is made, and how much algorithmic precarity (to quote Duffy) has to do with it.

I used to kinda hate it, when I was really focused on celebrity culture, when people asked me about my favorite celebrity — I think the muddling of ‘favorite’ and my object of analysis always felt kinda wrong. My favorites, though, were the ones whose texts were richest, whose understanding of the apparatus of celebrity were more sophisticated, or whose contradictions were most challenging. Who are those people in the momfluencer world for you right now?

Lately I have been really enjoying following Amber Fillerup Clark. I followed her for years because I kind of had to — she’s an OG Mormon blogger — but I didn’t find her posts personally engaging. She’s a vigorous adherent to influencer best practices: a unifying colour theme that defines her entire feed, beautiful travel photos, bathing suit shots, many, many closeups of the family snuggling. When I mentally zoom out and visualize the whole Amber Clark aesthetic it’s a blur of dusty peach and terracotta, blonde hair, and white teeth. There’s just an incredible cohesion to her entire aesthetic. Her family is beautiful and her house is a palace but historically her personality has felt a little underdeveloped in her posts. I guess I found her “affective expertise” a little lacking.

Lately she seems to be coming into a new phase of posting more candidly. I think it might be partly a consequence of her follower base becoming more partisan over the last few years, and maybe she’s felt pressure to express her own beliefs more, but I’ve never spoken to her so I don’t know for certain. She does this through AMAs in her stories, which of course is great for her engagement. She’s begun writing about her complicated relationship with Mormonism, and even touched on subjects that are really not standard for LDS influencers, like her own sexuality, masturbation, her feelings about the church’s attitude toward LGBTQ folks.

From my perspective, she’s experiencing growth as an individual and managing to incorporate it into her feed in a way that feels sincere. She has a huge following so in a way, she’s in this privileged financial position where maybe she can “afford” to risk turning off some followers, as long as her brand partners are cool with it. It makes me wonder if momfluencers with smaller followings, who are more precarious, have to be more conservative about what they share.

In that Times piece, I talked about the evolutionary stages of the mamasphere, and I wonder if the next phase we’ll see is “real talk,” which used to be the purview of all mommyblogs, becoming a mark of privilege.

I highly recommend subscribing to Kathryn’s newsletter here — and join me in delighting in her Twitter feed.

I got distracted at the top by that Ballerina Farm account. I would LOVE for someone to publish 10,000 words on the rise of what I call “Performative Farm.” I grew up on a farm in Iowa and I cannot abide the Farmhouse aesthetic trend or the rise of people with means setting up shop on a ranch or farm that they clearly do not rely upon as a livelihood and how this new cultural rural turn intersects with country music, evangelicalism, late-stage capitalism, white identity and conservative/libertarian politics.

When I was a kid in the 80s/90s there were a few former hippies who lived around our farm in older farmhouses who mostly worked in town but liked being out in the country. Other than that, it was all families who were farming to make a living. This meant raising crops to sell at market to earn money, mostly. However, the rise of corporate farming has mostly eradicated the family farm, so the Performative Farm is as much of a facade as the Momfluencer who is performing a sort of domesticity and motherhood that they imagine a bygone era to be like. It is not based in reality and plays heavily to a nostalgia that also isn’t based in reality. The reality is, since at least the 1970’s, family farming has been barely sustainable and the “rustic” charm manufactured by Pottery Barn or Magnolia is nothing more than a fantasy that never was.

I have stayed well and clear of the mamasphere, although it does pop up from time to time. The posed photos, the bible quotes, the weird visual screechiness of the too well scrubbed settings, the bad decorative taste- no thanks.

Motherhood- especially White Motherhood(tm) has always been performative in this country- and has always had a price to it and come AT a price. That social media is the newest version of this does not surprise me one bit.