Do you find yourself opening this newsletter every week? Do you value the labor that goes into it? Have you become a paid subscriber? Think about it!

Many of the people who read this newsletter the most are people who haven’t gone over to paid. I’m constantly saying I’m going to pay for things and take weeks to actually do it, so I get it. But maybe today is your day.

I remember the first eulogies for the rom-com from the early 2010s, usually a mix of they don’t make them like they used to and whatever happened to the mid-budget adult movie and why do they keep trying to make Justin Timberlake, Actor, happen. And it’s true: the rom-coms from that time felt a lot like a half deflated helium balloon, just kinda moving around your apartment, waiting to collapse. But a rom-com revival has been in the works for years, slowly gaining steam on Netflix and Hulu and other subscription services, where algorithms can override old-fashioned industry wisdom about who watches movies and what sort of movies they actually want to watch.

Genres have lifecycles; sometimes they go into hibernation, but they rarely disappear altogether. The existing structure of the rom-com was ill-equipped to deal with the late 2000s and 2010s; it had to be bent and challenged and reimagined to deal with texture and shape of love, meet-cutes, fantasy and romance today. I love thinking about this stuff, and am so grateful to have found Scott Meslow’s deeply layered new book, From Hollywood with Love: The Rise and Fall (and Rise Again) of the Romantic Comedy, which combines meticulous archival research and interviews with a framework that crystallizes the successes (and abject blindspots) of the (recent) genre. I apologized to Scott when I sent him these slightly curveball questions — I’m clearly working through some of my own ambivalence with the genre — but his answers are fantastic, and indicative of the care and detail of the book itself.

Enjoy, buy the book for every person in your life who’s watched these movies on repeat, and leave some questions for Scott in the comments.

Can you set the scope of your book for us? I think a lot of people are going to ask “but why not go back to screwballs” or “what distinguishes a romantic comedy from a romantic dramedy” or “why not Sex and the City.” All books need some sort of framework, so why did you choose this particular one? What did it illuminate that a larger scope wouldn’t have been able to?

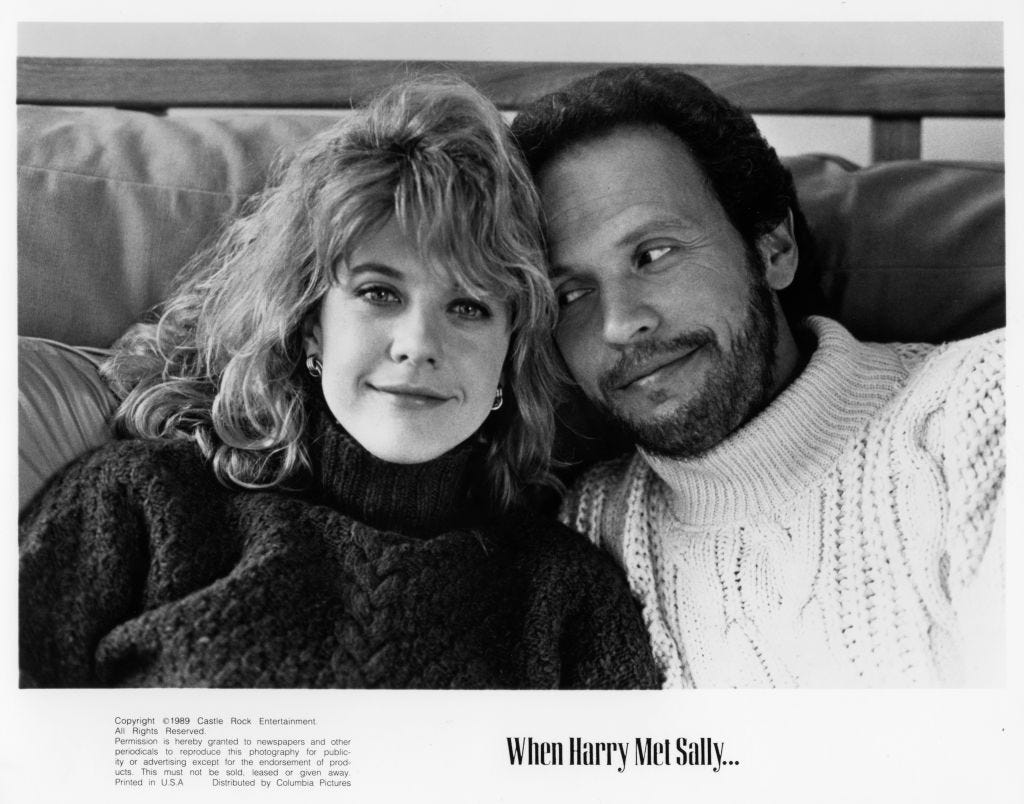

The book covers a little more than 30 years, which I’ve called the “modern golden age” of rom-coms — starting with When Harry Met Sally in 1989, and ending with the To All the Boys trilogy in 2021. The honest answer is that I was trying to walk a very particular tightrope here: What’s the best balance I can strike between breadth and depth?

One of my reasons was practical. I wanted this book to be an actual history of these romantic comedies — made up, whenever possible, of interviews I personally conducted with the people who made these movies. Even starting the timeline as recently as 1989, there were some gaps I couldn’t fill without archival quotes: When Harry Met Sally and Pretty Woman were essential to the story I was telling, but I obviously couldn’t speak with Nora Ephron (who died in 2012) or Garry Marshall (who died in 2016).

But as I winnowed down the list of rom-coms to cover in their own chapters — I started with something like 70 or 80 contenders, and ultimately settled on 16 — I realized that When Harry Met Sally really was the ideal starting point (as much as it killed me that beginning that left Moonstruck on the cutting-room floor).

For starters: Beginning with When Harry Met Sally put Nora Ephron at the top, and for good reason; by writing When Harry Met Sally and directing Sleepless in Seattle and You’ve Got Mail, she did more to both embrace and entrench rom-coms in the ‘90s than any other filmmaker. As a bonus, centering Nora’s story gave me a bridge into the genre’s past, because her parents Phoebe and Henry were rom-com screenwriters too.

As I outlined the book, I found that zooming in gave me space to focus on movies that might be easier to dismiss, or at least treat as a footnote, if I were examining a longer timeline. I am a huge admirer of My Best Friend’s Wedding, which I think is so much more risky and subversive than it often gets credit for — but if I were trying to cover a century of Hollywood romantic comedies, it could easily be just a paragraph or two in a Julia Roberts chapter, wedged between Pretty Woman and Notting Hill.

I felt a similarly strong pull to write about No Strings Attached and Friends with Benefits, which may not be classics, but reveal something very interesting about Hollywood’s fumbling, confused, somewhat earnest (but ultimately half-hearted) effort to explore how young people were dating circa 2011. In a survey of the romantic comedy that stretched back to Shakespeare’s time, I can’t imagine those movies would merit much attention — but they do open a lane to a very interesting conversation about how American cultural norms and ideas about sex and relationships were shifting, and I wanted to dig into that subject too.

And finally: I wanted to tell a larger story about the rom-com genre itself — and as the subtitle of my book says, I think there’s a great dramatic arc from the ‘90s to today. Rom-coms peaked, disappeared, and (I’m arguing) are back on the rise. The story of why those things happened, over those ~30 years, seemed to be worth telling.

You talk about the ways in which Hollywood was industrially set up in the ‘90s and 2000s to allow mid-budget romantic comedies to flourish — a world “where the stars still had more to do than stuntpeople, and where a chase through a crowded city street could end with your soul mate giving a teary-eyed speech instead of a punch from a supervillain.”

I, too, have so much nostalgia for that time — and the mid-budget movie in general! — but also struggle to square that nostalgia with the fact that Hollywood was also almost exclusively producing narratives featuring straight, white, slim characters falling for other straight white characters. (There are exceptions, of course, and you cover several of them…and yet!) What’s more, reading through so many of these chapters, I remember the particular pleasures of the movie — and then I kinda think, wow, I forgot just how quietly fucked up this movie is. See especially: the fatphobia of Bridget Jones’ Diary, the entire plot of Maid in Manhattan, the fatphobia of Love, Actually, the shrewification of Katherine Heigl’s character in Knocked Up.

Can you have industrial nostalgia while also interrogating how that industry was also often so limiting — and for a lot of us, really damaging in the ideas we internalized about the sort of person who deserved love?

For starters: The automatic default to whiteness/straightness/thinness in Hollywood — definitely true then, and mostly true now — is completely inexcusable. I don’t think you can write anything thoughtful about rom-coms without acknowledging that problem directly. And I don’t think it’s incompatible to say you love Nora Ephron (I do!) while acknowledging that it’s bad that she was making movies almost exclusively about white, wealthy urbanites (clearly true!).

It’s even worse that Hollywood, as an industry, rarely seemed interested in anyone much more than that, even when movies that deviated from the mean turned out to be hits. (I cover Waiting to Exhale in the book, and it was infuriating to talk with Terry McMillan about how Hollywood, collectively, just didn’t get it, even after Waiting to Exhale was the top-grossing movie over the Christmas frame in 1995.)

I think the four movies you specifically mention are good examples that cover a wide range of thoughtful/thoughtless approaches to this subject, so let me take them on individually:

1.) The tabloid coverage of Bridget Jones’s Diary, and especially Renée Zellweger’s body, was truly awful — I remembered it being bad, but it was still very sobering to dig through the archives, and realize just how bad. But I think Bridget Jones’s Diary itself is a little more thoughtful about it. Bridget spends a lot of time obsessing over her weight, but in my reading, the columns/books/films weren’t endorsing a culture of toxic and unreasonable expectations for women — they were reflecting what was already happening in the culture, and at their best, challenging it.

Everyone remembers Darcy’s big line to Bridget: “I like you. Very much” — which he has to say twice, adding “just as you are,” before she believes it. What gets lost, I think, is Bridget’s line in the middle: “Apart from the smoking, and the drinking, and the vulgar mother, and the verbal diarrhea…” I imagine she would have gone on speaking, listing other negative qualities she ascribes to herself, if Darcy hadn’t interrupted with such a definitive statement. Darcy sees exactly who she is. It’s not that he doesn’t see or doesn’t care about any of the “flaws” she obsessively chronicles in her diary — it’s that he likes them. I think that’s a really nice scene about the gulf between our (often toxic) self-images and receiving unconditional love and acceptance. Even though I watched that movie like 8 times while I was writing this book, I still get a little choked up at that bit.

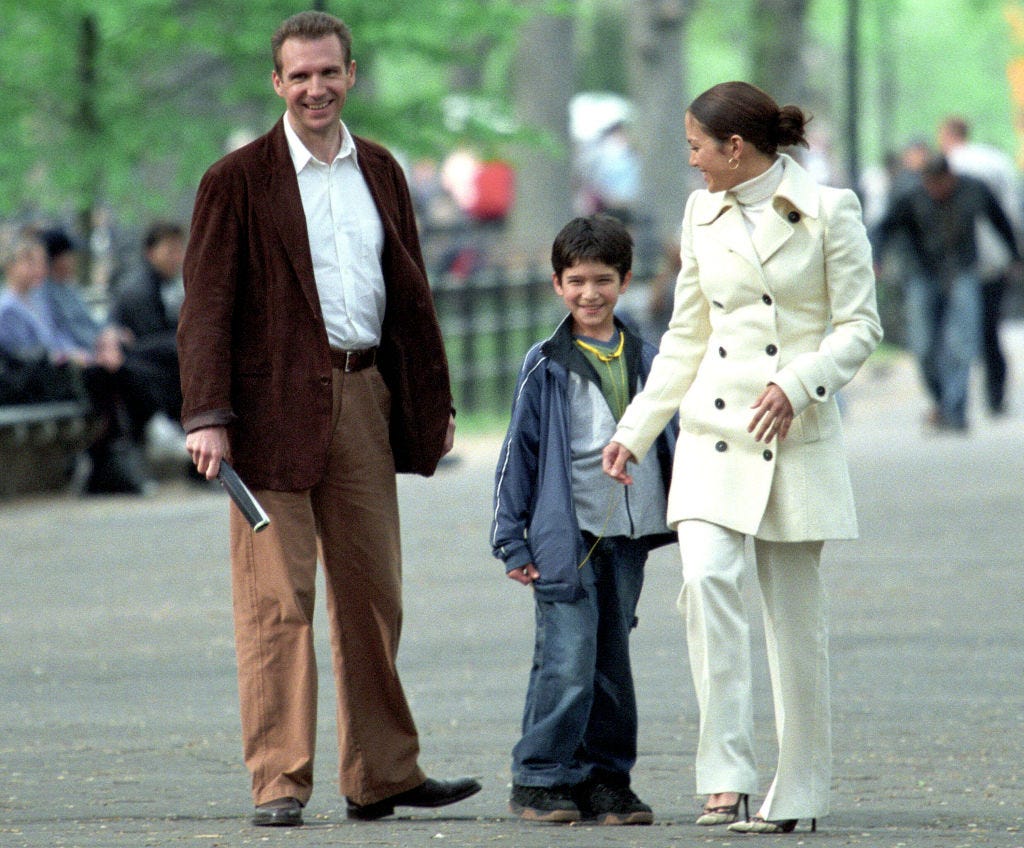

2.) Maid in Manhattan is a weird one. I don’t think it’s a very good movie, but it would be a worse movie if it had starred Sandra Bullock or Hilary Swank, both of whom turned it down before Jennifer Lopez signed on. Casting a nonwhite actress in the lead role makes Maid in Manhattan about racism in a way it is clearly not brave enough to seriously grapple with. There are scenes like the one where J.Lo says to Ralph Fiennes, “The first time you saw me, I was cleaning your bathroom floor! Only you didn’t see me” that ring really true — but the movie doesn’t really want to reckon with that, because we’re also supposed to like Ralph Fiennes and want him to end up with J.Lo. So it’s just kind of a mealy-mouthed mess, but an interesting one, and an instructive snapshot of Hollywood being caught flat-footed.

3.) There is nothing good or defensible in how Love Actually talks about Martine McCutcheon. It’s disgusting.

4.) Knocked Up is another one I have mixed feelings about. Judd Apatow’s whole thing (in this era) was blending romantic comedies and coming-of-age stories about schlubby but essentially sweet dudes who need to get their shit together. He is clearly more interested in the men than the women, and you could convincingly argue that their romantic counterparts are reduced to playing the role of obstacle, and finally solution, in his hero’s journey. But I do think Katherine Heigl, while clearly secondary to Seth Rogen, is more than just a prop in his Knocked Up journey. Her comic delivery is pretty low-key and deadpan, so her jokes can get lost in all the bro-y shout-y stuff, but she’s very funny. There’s also a great runner about trying to hide her pregnancy from her bosses at E! — then discovering that they cynically view her pregnancy as an asset for a job doing red-carpet interviews — and none of that involves Rogen at all.

I think, unfortunately, this is also where the real world intrudes on the movie. I cover this in a lot more detail in the book, but it is bananas that Katherine Heigl’s one small and entirely fair criticism of Knocked Up in a Vanity Fair profile became such a big story, and continues to color how people view her more than a decade later. I have less of a problem with how Knocked Up treats Heigl than how she was treated in the real world.

As for the big question — can we love these movies and interrogate them? — I think so! I wrote a whole book about it! There’s a scene I like in To All the Boys I’ve Loved Before where Lana Condor and Noah Centineo are watching Sixteen Candles together and he asks if the Long Duk Dong character is “kinda racist,” and she replies, “Not ‘kind of,’ extremely racist.” This scene goes a little too easy on Sixteen Candles specifically, but I do think the principle is a good one: Enjoy the movies you enjoy for what’s wonderful about them, and speak out, clearly and forcefully, about the parts that are fucked up.

When I was in grad school, I wrote this sprawling star study of Julia Roberts, which included a lot of digging into the history and mythos around Pretty Woman. I thought I knew a lot of the backstory of the original script and development, but it’s even more twisted than I remembered. Can you recount some of that story? Also what does it suggest about the rom-com industry that the only way a sex worker could be featured in a romantic comedy is if it’s effectively Disneyfied into a fairy tale? I can’t get the bit about how Jeffrey Katzenberg wanted Vivian to be “fresh” to sex work — and the script needed to highlight her “unusual” cleanliness.

This is absolutely one of the wildest development stories I’ve ever encountered. For readers who have never heard any version of this backstory: Pretty Woman began as a buzzy but extremely dark spec script called Three Thousand. It is, more or less, the story of a psychopathic billionaire who picks up a sex worker and spends a weekend abusing and manipulating her. It ends when he literally drags her out of his car and onto the street. It does not read like a commercial movie at all, and it definitely does not read like a romantic comedy.

After a bunch of convoluted Hollywood business stuff, Three Thousand ended up at Touchstone, a Disney label geared toward adults. Garry Marshall, the Happy Days creator who found the right balance of light/dark for Beaches, was brought in to help figure out how this grim script could become a Disney movie. (It should be noted that J.F. Lawton, who wrote Three Thousand, was on board with these changes, and contributed several lighter drafts as well.)

The cleanliness stuff is so bizarre and funny — just a classic handwave of an answer from a Hollywood executive who thinks he sees a problem but can’t be bothered to engage with the material for more than like 30 seconds. “Oh, there’s an oral sex scene that might gross some people out? Just have her talk about… I don’t know, the importance of flossing for a weirdly long time, whatever.”

All that stuff (and the whole guiding principle of rewriting Three Thousand as a fairy tale) means Pretty Woman has plenty of lightness to it. But I do think the darkness from the original script that couldn’t be filtered out is, kind of paradoxically, part of the reason that Pretty Woman was such a huge mainstream hit. The movies opens by revealing that a sex worker has been murdered. The stakes for Vivian are pretty high, and she knows it, so it’s a big moment when she rejects Edward’s sleazy first offer to buy her a condo and let her go on living on his largesse as his L.A. girlfriend.

Even in the final cut, it’s still this close to being a pretty dark drama, and everyone making the movie knew it. Jason Alexander once said that Garry Marshall shot each scene at least three ways: One that leaned into comedy, one that leaned into drama, and one in which he encouraged the actors to do whatever felt right. I’d bet you could cobble together an interesting drama from the takes he didn’t use.

There’s a quote from Loretta Devine, who plays Gloria in Waiting to Exhale, that feels like it’s been delivered in some form in Hollywood every year. “...when I go to see casting people in L.A. it’s like they never saw the film — like they can’t face the fact that the story of four black girls did well.” And Terry McMillan’s addition: “That 14.1 million was black money. It was also a show of respect for me, the book, us. That’s what that was about. And, they couldn’t have made a larger statement. You guys need to pay attention.”

Audiences tell the industry what they want, and they give them a literally white-washed version — see, for example, Sex and the City, which McMillan and others commonly acknowledge “robbed” Waiting to Exhale without acknowledgment. Does the success of, say, Never Have I Ever and its subsequent iterations suggest that data-driven studios like Netflix are actually “paying attention?” Netflix is very cagey about its data, but it also understands people’s actual viewing habits and genre hungers in a way that so many previous execs only pretended to.

I am endlessly fascinated by Netflix, because their obsessive secrecy requires you to play Sherlock Holmes: You’ll never get a straight answer from them, but you can intuit a lot from what they’re doing — and because they have more raw data about what people are watching than anyone has ever had at any point in human history, you can bet that what they’re doing is whatever they think will make the most money.

This is kind of a depressing answer, because it’s cynical, but “what makes money” feels like the quickest path to real, lasting change in Hollywood. I would prefer it if the basic, obvious moral case for diversity was moving the needle, but the business case seems to be moving things faster. There’s a section in my book about how Sony refused to cast a white woman as Will Smith’s love interest in 2005’s Hitch because they thought U.S. audiences would have a problem with it. Last year, Netflix put out Single All the Way, a rom-com about a love story between a white man and a Black man, to basically no uproar from the boogeymen the studios are always conjuring up when they make lame excuses about their lack of diversity. There are still racist lines being drawn — it remains very rare for a Black man and a white woman to get cast as romantic leads — but I don’t see how executives can look at the reception of streaming movies like Single All the Way, or The Lovebirds, or Always Be My Maybe, or Hulu’s Happiest Season, and say, “audiences don’t want this.” Their excuses were always nonsense anyway, but with that much data, they’re harder to justify.

As for the studios: it’s all much more gradual, which makes it more frustrating. The studios are kind of like ocean liners: They can turn, but they do it very slowly. But I think there is at least awareness that change is badly needed, and I’m heartened by conversations I’ve had with some of the people I’ve interviewed: People who not only have some power to change things, but are already putting in the work to do it. Last year, I profiled Alana Mayo, the president of Orion Pictures, which was recently relaunched with an explicit mandate to focus on underrepresented voices. The first movie she greenlit is What If?, an upcoming coming-of-age rom-com a Persian cis boy and a Black trans girl, with Billy Porter directing. When she described that movie — as passionately as I’ve ever heard any studio executive describe anything — that felt like progress to me.

You make a pretty provocative but compelling case for the future of the rom-com in your conclusion — can you tell us more about the possibility of, say, “the Rom-Com Cinematic Universe?” What else are we going to see, moving forward?

Oh, let’s start with the Netflix Christmas Rom-Com Cinematic Universe, because it’s absolutely bonkers and I need more people to know about it. Starting with 2018’s A Christmas Prince, Netflix has been quietly building out this web of interconnected Christmas rom-coms. They’re set in a series of fake, vaguely Western European countries with names like Aldovia, Belgravia, Montenaro, and their main export seems to be Christmas stuff. The Princess Switch: Switched Again, which features Vanessa Hudgens playing no fewer than three separate characters, ended with the Christmas Prince couple showing up at the end, revealing that the Christmas Prince and the Princess Switch movies are set in the same universe.

Things have gotten way more complicated since then. Last year’s A Castle for Christmas revealed that two minor characters from The Princess Switch have snuck off to Scotland for a secret tryst: An entire, apparently canonical subplot that is not even revealed to the people who watched all three Princess Switch movies. Who needs the Marvel Cinematic Universe?

In broader strokes, I think rom-coms are following the same trends you can see across the industry. The studios seem to think — and, I’m sorry to say, have increasingly good proof — that modern audiences won’t go to movie theaters unless a movie is successfully sold as An Event (like a Spider-Man you just need to see opening weekend, Omicron variant be damned, so the cameos don’t get spoiled for you). I think you can see that principle at play in most of the studio rom-coms being released this year. Marry Me is a rom-com crossed with a J.Lo concert film. The Lost City is a rom-com crossed with an Indiana Jones (or, more simply, a Romancing the Stone). Billy Eichner’s Bros is, in a cultural sense, an Event in itself: A major studio rom-com centered on a love story between two gay men.

I was disappointed by Marry Me, but I’m hopeful about those other two movies (and Shotgun Wedding, and Ticket to Paradise, and the rest)! But at the very least, I think rom-coms have an extremely strong future on streaming. Basically everything that might make rom-coms unattractive to the studios makes them more appealing to the streamers. They’re relatively cheap and straightforward to make from a logistical standpoint; tend to require minimal SFX or other costly post-production elements; offer attractive leading roles for stars who want to show how funny and charming they are; and, when they really work, attract devoted fandoms and create opportunities to build on successes with more movies and TV shows. (See especially: The To All the Boys franchise, which already spans three movies, with a spinoff based on Lara Jean’s little sister Kitty on the way.) Netflix, Hulu, and Amazon have all increased their rom-com output over the past few years, and I think they’re just getting started.

And finally, what’s your sleeper rom-com fav to recommend to people who’ve seen all the hits?

If you’re looking for something modern that feels like it sprang directly from the classics, try Plus One (on Hulu right now). It’s a pretty classic rom-com setup: Two college friends, facing a grueling wedding season, agree to attend every event together, and gradually realize they might actually want something more than friendship. But those (pleasingly) familiar beats are punched up by an unusually sharp script and two very appealing lead performances from Maya Erskine and Jack Quaid, son of rom-com royalty Meg Ryan.

For something more experimental and offbeat: Check out Masaaki Yuasa’s 2017 anime romantic comedy The Night is Short, Walk on Girl (on HBO Max right now). It’s a hybrid of the rom-com and a classic “one crazy night” premise: A girl who can drink anyone under the table decides to go on an epic bar crawl, while the boy who has been crushing on her from afar tries to work up the courage to confess his true feelings. It is wildly unpredictable and absolutely gorgeous to look at.

And at the risk of blowing up my credibility right at the end of this Q&A, I’ll throw out an against-the-grain pick: Wild Mountain Thyme (on Hulu right now). It’s a very whimsical rom-com — some might say cloyingly so — starring Jamie Dornan and Emily Blunt as a pair of neighboring Irish farmers who would clearly be perfect together if Jamie wasn’t so inexplicably distant for reasons unknown. Wild Mountain Thyme got absolutely blasted by critics in 2020, and the big reveal is so bonkers that I could spoil it right here and you probably wouldn’t believe me anyway. But I don’t know, I watched it for the first time last week, and I found it kind of lovely? Take the specifics of the twist away, and you’re left with a story that advocates passionately for loving someone as they are, fully and completely, even if you don’t really understand it. I can’t help but find that kind of beautiful.

You can follow Scott on Twitter here and buy From Hollywood with Love here.

As a follow-up to this week’s piece about colonoscopies, I’d like to hear about people’s experiences with fibroids. Here’s how you can contribute.

I’m also looking for pitches to take over Culture Study for the week! The pay is $2000, and you can find more information here. Please circulate both calls widely!

Thank you for reading! If you value the labor that goes into producing this newsletter and find yourself reading it often, consider subscribing:

Subscribing is also how participate in the heart of the Culture Study Community. There’s the weirdly fun/interesting/generative weekly discussion threads plus the Culture Study Discord, where there’s dedicated space for the discussion of this piece (and a whole thread dedicated to Word games), plus equally excellent threads for Career Malaise, Productivity Culture, Home Cooking, Summer Camp Blues (for people dealing with the bullshit of kids summer camp scheduling), Spinsters, Fat Space, WTF is Crypto, Diet Culture Discourse, Good TikToks, and a lot more.

If you’ve never been part of a Discord: I promise it’s much easier and less intimidating than you imagine. Finally, you’ll also receive free access to audio version of the newsletter via Curio.

As always, if you are a contingent worker or un- or under-employed, just email and I’ll give you a free subscription, no questions asked. If you’d like to underwrite one of those subscriptions, you can donate one here.

If you’re reading this in your inbox, you can find a shareable version online here. You can follow me on Twitter here, and Instagram here — and you can always reach me at annehelenpetersen@gmail.com.

This was great but now I need both an extensive follow-up about Drew Barrymore from the late 1990s through 2010's Going the Distance (Never Been Kissed! Wedding Singer! Home Fries! Ever After! Fever Pitch! 50 First Dates! He's Just Not that Into You! -- such an incredible mix of seriously problematic and kind of interesting/weird movies) and about 12 hours to binge-watch all those movies. Which I do not have.

I would love, love, love to see all of Jasmine Guillory's romcom novels turned into films. Not only are they racially diverse, there are prime roles for 50somethings ("Royal Holiday"). And like the Netflix Christmas movie universe, all the main characters are relatives and/or friends of one another.