Note: This is the second installment in Culture Study’s Age of Houseplants series. You can find the first in the series here.

In 1975, New York Magazine published a cover story on “The Secrets of the Plant People.” The bulk of the issue was dedicated to plants, including articles on “The Orchid Underground” and the “High, Dry, and Handsome” joys of cacti cultivation. All of the houseplants featured in the magazine — including ferns and African violets — were positioned as potential obsessions. But none were quite as addictive, the author of the special section, Richard W. Larger, warned, as begonias.

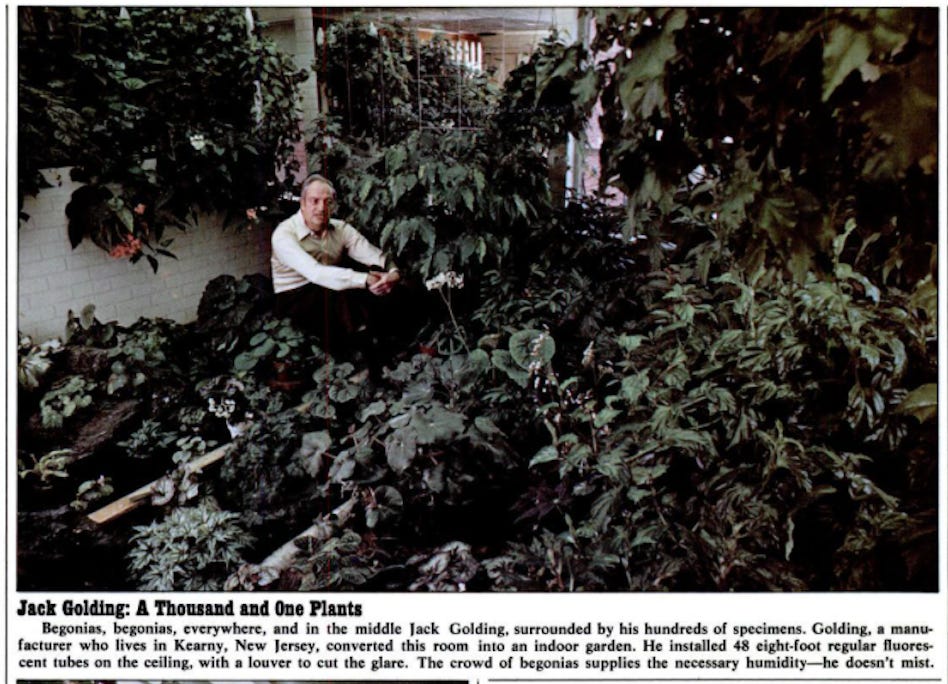

“Be forewarned,” Langer wrote. “Once you start growing begonias, you may be unable to resist more, whether you have room or not.” One “begoniac” had amassed thousands of begonias, cultivating them from seed and cuttings, and nurturing them a series of 48 fluorescent bulbs installed in his New Jersey home.

The indoor plants-focused issue of New York Magazine was its third in three years — evidence of houseplants’ stunning repopularization over the course of the 1960s and ‘70s. Each issue was filled with tips, advice on the best new spots to seek out plants in the tri-state area, and contact and meeting information to find fellow indoor plant devotees.

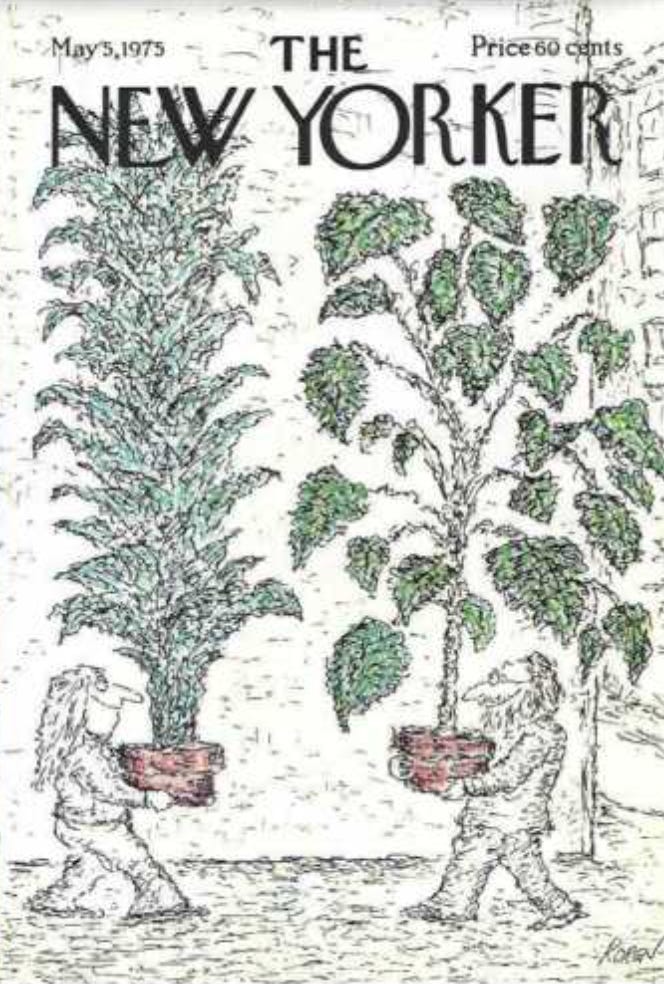

There were glorious photos of New Yorkers in their dwellings, creating mini-greenhouses on their co-ops roofs or nurturing vines around the single window in their railroad apartments. The growing obsession was lightly satirized by The New Yorker, which published three of its own house-plant-centric covers in 1975 and 1976. (The joke, as with so many low-stakes New Yorker cartoons, is that something has not that important has become overly important to the point of mild ridiculousness).

As I wrote in the first installment of this series, this low-key obsession might sound familiar — we’re currently in the midst of the biggest houseplant boom since the late ‘60s and 1970s. An estimated three fourths of adults have a houseplant in their home, and household spending on houseplants has climbed fifty percent since 2016. Part of the popularity can be traced to pandemic isolation, but the new wave of indoor plant “magnificent obsession” began well before 2020. Houseplants said something about the people who cultivated them in the early 1600s, which was different than what they said about someone in the 1860s or 1960s, or the present.

With this piece, we’re going to try and unlock some of those aesthetic motivations of those 1960s and ‘70s “plant people.” If you’re of an age to have memories from that time, you might have memories of a growing number of houseplants in your home: rubber trees, endless ferns, snakeplants (formerly known as ‘Mother-in-Law’s Tongues), proliferating spiderplants suspended in macrame holders, dusty Christmas cacti, clusters of fuzzy-leaved African violets, knobby jade plants, unchanging and treacherous barrel cacti, and, of course, the slowly dying ficus. (A lot of great memories in the replies to the tweet below)

During World War II, interior design had taken a backseat to other priorities. But as people began to rebuild their lives, they often found themselves in more modern — and far more contained — spaces than ever before. If the war forced people to focus outward, towards societal and allied strength, then the post-war period was typified by a gradual turn inward, to the comfortable nucleus of the family unit, ideally in an increasingly automated and self-contained home.

In Potted History, Catherine Horwood underlines that even as many UK families found themselves with access to, say, an electric laundry machine for the first time, many had little green space. Wives were also implicitly charged with making their space as welcoming and nourishing as possible for the “work-weary” husband. Who could point out ways they didn’t even realize they were failing as wives and mothers, and then give them helpful consumerist tips on how to remedy those failures? Women’s magazines, of course! Ideal Home and Good Housekeeping in particular, but there were so, so many more.

If you didn’t have ample outdoor space to turn into an edenic splendor, the houseplant was a suitable alternative. And if you did have outdoor space, like the American suburbs, the goal was to decorate it and transform it into entertaining space, while also turning the indoors into an eden. The overall aim, as the comedy duo Michael Flanders and Donald Swann put it in their 1956 song “Design for Living,” was a scenario in which “the Garden’s full of furniture / and the house is full of plants!”

In 1952, Tom Rochford — owner of the UK’s storied Rochford Nursery, which dated to the late 1880s — began using the term “houseplants” to describe all indoor plants (previously referred to as “potted plants”). At that point, Rochford’s Nursery was growing more than 100,000 plants every year, delivering them to locales across the country in green vans, distinguishable by their ficus logo and the slogan NO HOME IS COMPLETE WITHOUT LIVING PLANTS.

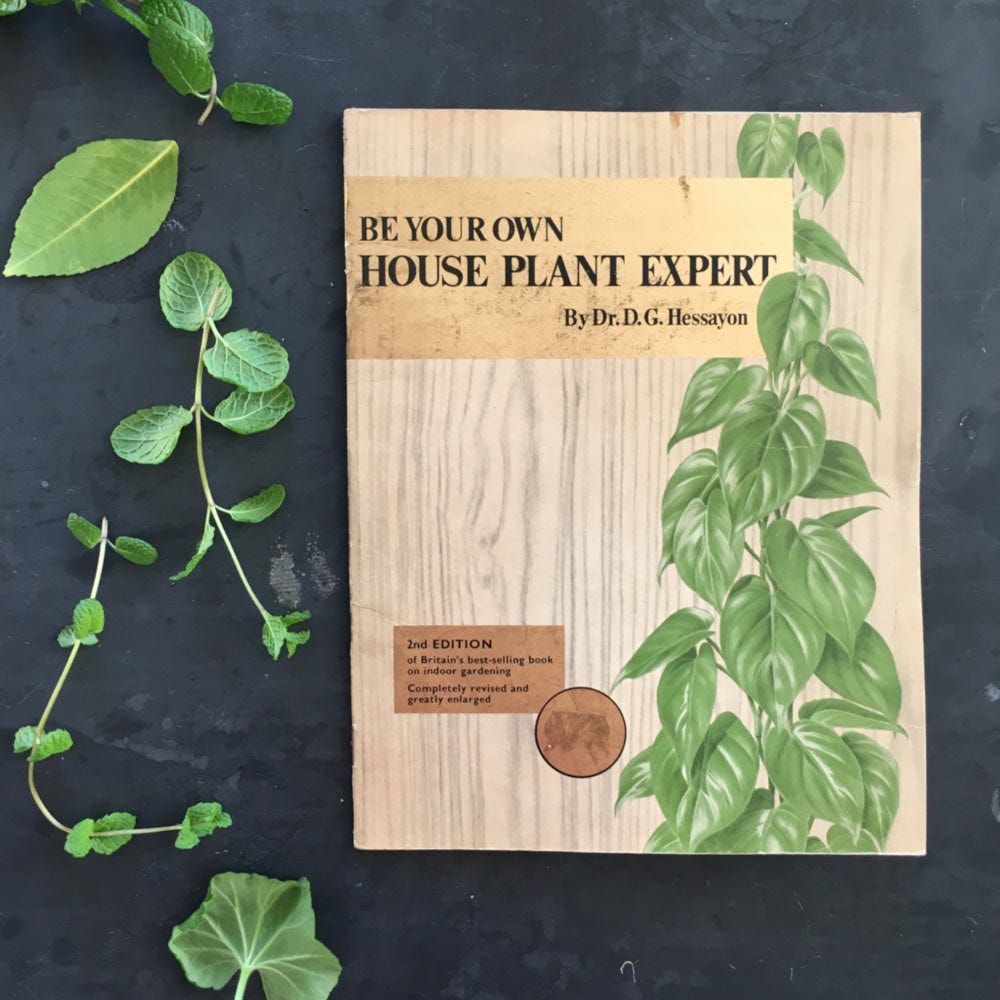

Four years later, the BBC launched Gardening Club, featuring Percy Thrower, who would go on to become the Bob Villa/This Old House of gardening in the UK. One of his first guests was Rochford, there to address the common problems and ailments of various houseplants. In the aftermath, Rochford received thousands of queries about individual houseplant problems. There was clearly a hunger and market for house plant expertise, and David Hessayon, an employee at fertilizer manufacturer Pan Britannica, convinced his bosses that he should be the one to write it — and they should be the ones to publish it.

If you grew up in the UK, chances are high that you own or have lived in a household that at one point owned some version of Be Your Own House Plant Expert. It sold over fourteen million copies, and spawned dozens of sequels, offshoots, knockoffs, both in the UK and the US. The contents are pretty straightforward to contemporary eyes, but at the time, knowledge about how not to fuck up your plants was a coveted commodity. Without the internet or houseplants Instagram, these books felt like bibles.

In the UK, Rochford made it possible to possess the plants; the books and shows and magazines made it possible to turn them not just into a hobby, but a form of art. “Gone were the labour-intensive conservatories, damp ferneries, ornate jardinieres and elaborate Warden cases,” Harwood explains, gesturing to the preferred mode of 19th century houseplant cultivation. Instead, experts recommended svelte bamboo trellising, mid-century modern plant stands, and macrame hanging baskets. In the UK, some of these structures were designed by students at the Royal College of Arts; others, like the ubiquitous macrame hangers, were the result of houseplant cultivation gradually intersecting with the UK’s 1970s craft revival.

In the United States, the late ‘60s and ‘70s embrace of what we might call the “houseplant aesthetic” was part of what sociologist Sam Binkley has called the “loosening” of consumer culture, in which middle-class Americans embarked on a larger aesthetic and experimental project of “getting in touch” with a more earthy, crunchy, authentic sense of self.

“In millions of American homes,” Binkley writes in Getting Loose, “food would become purer, its naturalness less constrained by additives and processed ingredients; clothing would become more sexual and revealing; home decor more authentic and rustic; sex more orgiastic; relationships more earnest and sincere.” Think The Whole Earth Catalog, think health food stores, think of the Back to the Land movement, think Benjamin Spock’s style of parenting — and think, well, of houseplants in macrame hangers, placed amongst the “formless beanbag chairs flopped onto shag carpets and creative natural fabric wall hangings” that typified the dwelling of the “loosened” subject.

Think, too, of Sunset Magazine, which had rebranded itself as the “Magazine of Western Living” after World War II, and helped refine and propagate the quintessentially post-war California “inside/outside experience.” The Sunset vision of the loosened natural world was always notably more bourgeois and less crunchy than the one on display in, say, the The Whole Earth Catalog, but the audiences weren’t as dissimilar as one might assume. Both would be into living in a space like this:

Or this:

Scroll through The ‘60s Interior account, and you’ll see the vibe on repeat. Natural light, light wood, sumptuously textured and colored fabrics in various earth tones, and plants, always plants. It feels wild but coherent — loose.

“To live the loose lifestyle was thus to incorporate the conflicting imperatives of disintegration and renewal constitutive of the modern experience into a single moment or story,” Binkley writes, “to relate the distressing momentum of modern flux and all of its incumbent freedoms to a reassuring narrative of meaningful growth and personal discovery.” And what else is a house of flourishing houseplants but an opportunity to narrativize growth?

In the first installment of the series, we saw the ways in which indoor plant cultivation became gendered: there was the over-cluttered, Victorian, musty way of doing it (feminized) and the high modernist, precise, architectural way of doing it (masculinized). The 1960s and ‘70s style was typified by a reversion to the more effusive style, with spaces built to accommodate and center plant life, but with (often masculinized) expertise to guide and control the worst feminine plant cultivation. In an indoor plant handbook for Woman’s Own, for example, published in 1969, William Davidson attributed 75% of all indoor plant deaths to “the overindulgent housewife who is ever ready with the watering can.”

The ideal was to toe the line between the sort of marvelous, thriving “loose” arrangements on display in magazines like Sunset and House Beautiful and a souring, aging overabundance. You wanted your house plants to be fresh and hip, not a mini, musty Grey Gardens. The way you arrived at that fine balance: constant guidance from experts, from books, and, of course, from the magazines themselves.

The advice inside these houseplant-focused issues of New York Magazine is actually quite practical — how to grow window herbs, for example, without spending hundreds of dollars, or how apartments with radiators that suck all the moisture from the air can provide a happy home to a cactus. But the softly ridiculing undertone of the cover art periodically seeps through, in spreads like this one, from the “Secrets of the Plant People”:

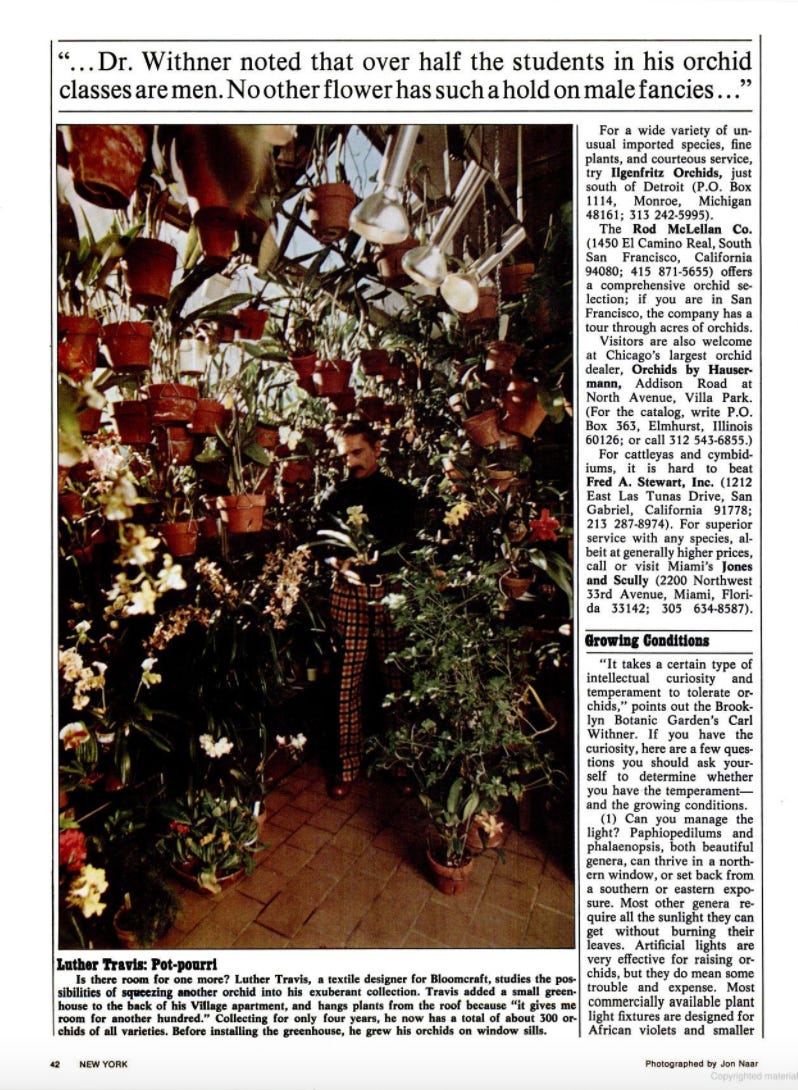

What do you do with a statement like “It takes a certain type of intellectual curiosity and temperament to tolerate orchids” juxtaposed with “No other flower has such a hold on male fancies”? There’s so much going on here! Men only like HARD PLANTS! But also hard plants are like difficult women!! And once you get started, the next thing you know you’re this guy, with a house full of orchids and no room for a life!

Much of New York’s advice was directed towards readers trying to craft that “reassuring narrative of meaningful growth and personal discovery,” as Binkely put it, within the confines of a New York apartment. But so many of the people highlighted in its pages are those who refused those confines, and, as a result, have found themselves drowning in their own obsessions. Most are older women or aging men, and they are all pictured alone, conceptually marooned in a sea of plants. Each mini-profile feels like a sort of object lesson: of the wages of too much passion, and not enough self-awareness and actualization. The only thing growing are the plants.

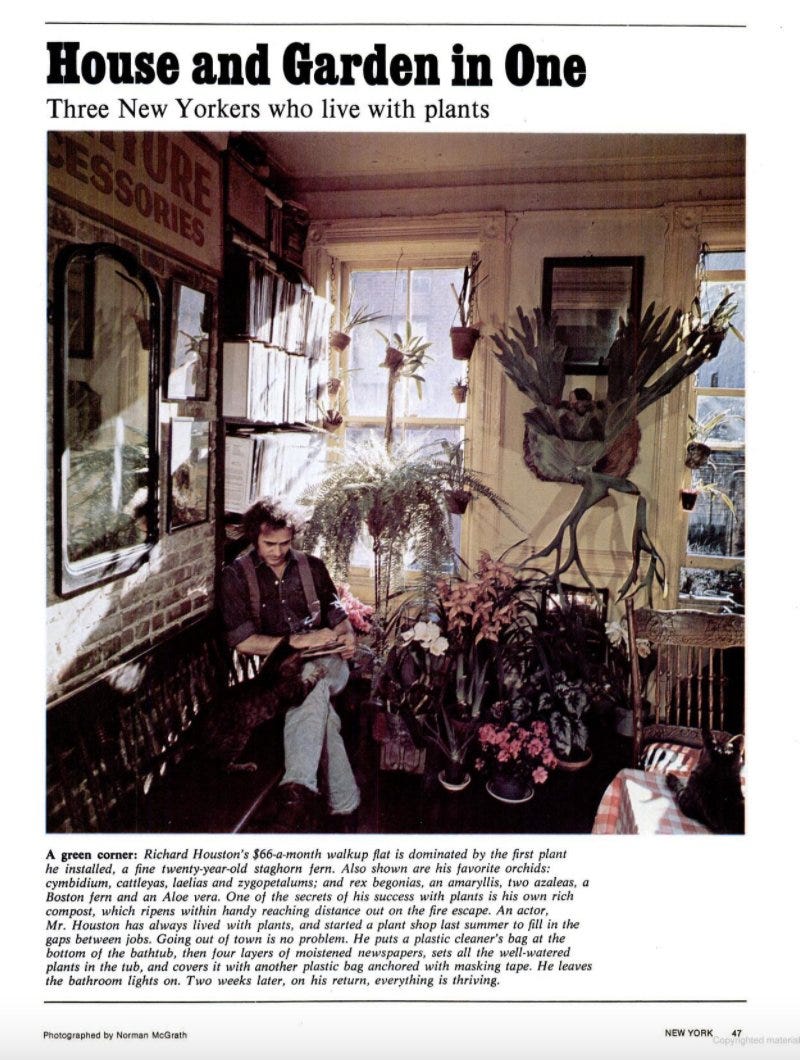

The exception: this guy.

This guy’s the Urban Houseplant Ideal. He may not have a house with an atrium and a conversation pit, but he’s got an affordable flat (today’s dollars: ~$450), a masculine centerpiece of a 20 year old staghorn fern, and good light on his reading chair. He’s an actor with a seemingly casual side hustle of running a plant store. He even makes his own compost on the fire escape. It’s clear that he loves and respects his plants, but he’s not dangerously obsessed with them, as evidenced by the watering scheme that allows him to leave for weeks at a time. This guy is loose! He’s writing his own growth story, you can just tell.

But as Binkley points out, in just a few years, this style of guy — this style of life — would be subsumed by yuppieism, and the corresponding “tightening” of the loose style, as boomers gradually “abandoned social conscience for the pursuit of social prestige and career success.” Yuppies weren’t against house plants, per se, but they certainly didn’t have time for orchid cultivation or any other sort of time-intensive hobby that didn’t provide a means of optimization (jogging) or business networking (racquetball).

And so the layered, light-filled house plant style, like so many other components of ‘70s looseness, were replaced by the shiny formica, smooth synthetics, colors straight out of a Play-Doh container, and an anxious hunger for ever-escalating profit. Which isn’t to say that house plants disappeared — they never actually, truly, disappear, no matter the trends. In many cases, they just receded into the background, dusty and neglected, like so many of the boomers’ barely remembered dreams.

In the next (and final) edition, we’ll look at how the houseplant was finally optimized in a way that would appeal to the inheritors of the yuppie sensibility. To make sure it ends up in your inbox, subscribe now.

$450 New York appartment. FOUR HUNDRED AND FIFTY DOLLAR APARTMENT.

BRB, gotta go guillotine the entire for-profit real estate industry.

Can’t stop worrying about the abundant mold Begonia Man is also growing 😬