Do you read this newsletter every week? Do you forward it or text it to your friends?? Do you value the work that goes into it???

Consider becoming a subscribing member. You get access to the weekly Things I Read and Loved at the end of each Sunday newsletter, the massive link posts, and the knowledge that you’re paying for the things you find valuable.

Plus you get access to this week’s threads — like yesterday’s behemoth 900+ TBR-busting one on “What You’re Reading” (every month, these make me so happy) and last Friday’s on “How You Want To Be Parented” which is useful and clarifying whether you’re parenting an adult or an adult thinking about how things could be different.

I have an intense sense memory of what the BuzzFeed office felt like right around 4:30 pm. In the winter, it’d already be dark, and the lights of the city would have replaced the sun. The sound of Manhattan traffic, always present, seemed to intensify. My stomach would feel empty and slightly sour; my shoulders sore and weighed, despite the very fancy Aeron chairs supposedly remedying our posture. My eyes would burn from too much time staring at the computer screen through contacts.

There was no work getting done. Maybe you had a bullshit conversation with a coworker that would someday turn into an idea, but mostly you just looked at the three empty seltzer cans on your desk and thought “how am I still thirsty.” My brain and body were exhausted. And yet I would stay there until right around 5:50, when it was acceptable to start putting on your coats and gathering your things to make your way to the subway. We were still in the office, but it was effectively a dead zone.

A recent article in the Wall Street Journal entitled “The New Workday Dead Zone When Nothing Gets Done” bemoans the loss of these supposedly essential workday hours. (As with most articles about flex work, it’s talking specifically about salaried workers — a generally privileged class, but a class worth talking about because their understanding of how work should work and what workers deserve has ramifications on us all).

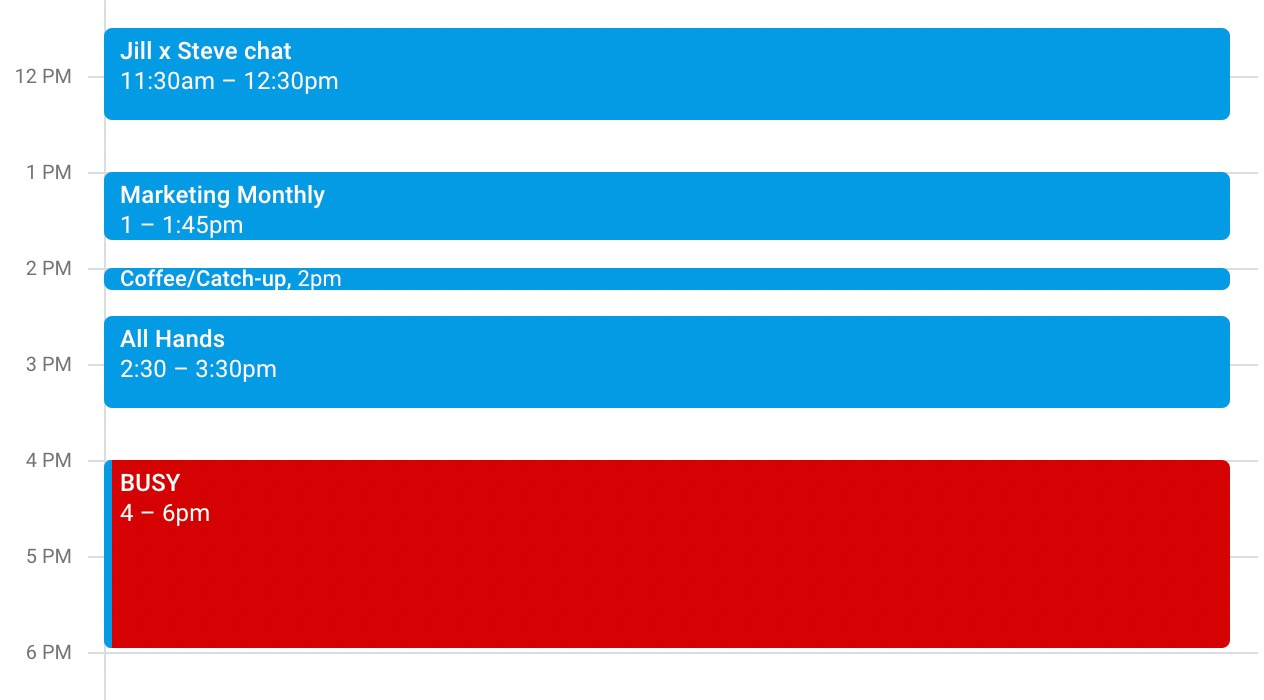

The article points to innovative research from Stanford scholars Alex Finan and Nick Bloom (who’s been researching the effects of remote and flex work long before the pandemic) on a pretty massive increase in weekday golf, along with an analysis of Microsoft Teams usage over a recent one-month period, which showed that virtual and in-person meetings between 4 and 6 pm were down seven percent from the year before.

In short: some data suggests that it’s harder to schedule meetings during this time, but mostly it’s a vibe. For example: Maria Banach, a pharmaceutical operations director in Oregon, told the Journal that “Scheduling meetings has become difficult, and I’ve learned: Do it in the morning and never on Friday.” Then there’s the chief learning officer at Deloitte U.S., who reported that he’s had to make once mandatory end-of-day training sessions into recorded tutorials that employees can consume on their own schedules.

Here’s a larger taste of the tone of the piece:

“Bosses can drag employees back to their desks, but good luck keeping them there until the end of a 9-to-5 workday or beyond. The 4-6 p.m. dead zone is one reason so many executives are cranky about hybrid work. They say it’s the hardest time to reach people, and things would be easier if everybody were present and accounted for in person, even though many workers seem to be leaving offices earlier, too.”

And also:

Accommodating employees’ personal appointments—happy-hour yoga, a teen’s tuba lesson—can be necessary to recruit and retain top talent, several business leaders tell me. They add it sure makes getting a quorum at meetings tough, though. Others, especially child-free workers, complain that their workdays have become longer and less predictable since it became widely acceptable to take breaks during normal business hours.

So is this a problem…or a “problem”? Put differently, is it an actual problem that demands remedy — or are some bosses reacting to changes in the way work is organized?

When I asked this question on Instagram, the response was overwhelming. People are working a lot less between 4 and 6 pm. But it’s not an actual problem, because there are so many other hours of the workday. (If there’s a an actual problem, it’s the way in which the triple-peak workday can make it feel like you’re really just working all the time — but that’s the subject of a difference post).

Either employees’ bosses have realized as much and instituted some sort of “core hours” where workers should be available (a lot of 10-2ish, shifted slightly according to time zone needs) or they just make it work, and made it work before the pandemic, too. Why? Because the rest of life, at least for anyone with caregiving responsibilities, has assumed availability during those times.

Daycare, preschool, elementary school, middle school, Boys & Girls Club, soccer practice, dance practice, robotics club, summer day camp, the list goes on — they all at some point before 6 pm, which means that workers can either 1) pay someone to pick kids up and provide more care; 2) be lucky enough to have a family member capable of handling pick up and supervision; 3) have a partner or friend with the flexibility to cover it; or 4) do it themselves. Given the realities of our current childcare economy, that means you can be very rich, very lucky, or in a relationship where one person doesn’t work for pay or works in a job with consistent flexibility.

If a salaried organization has a “dead zone,” then, it probably has caregivers in its workforce. If it embraces that dead zone, it’ll make it easier for those caregivers — regardless of gender — to stay in its workforce. If it draws hard lines around it, it will reinforce the type of people who will thrive in that organization: those who can afford, literally or figuratively, the costs of outsourcing necessary interstitial care.

If you’re not currently in a caregiving scenario, you might be wondering: WELL, PEOPLE MADE IT WORK BEFORE! School has always ended before 6 pm! You just dealt with it! And all the caregivers will answer: things are not like they were when we were growing up, and they are not even like they were before the pandemic — in so many senses of the term.

Affordable after-school programs are critically understaffed and have massive waiting lists — and if they do have enough staff, there often aren’t enough bus drivers to transport them. Several states have strict laws about what age kids are allowed home alone, and depending on your neighborhood and race and class presentation, neighbors will call if they think your child is left unsupervised (in Illinois, the minimum age is 14; in Colorado and Delaware, it’s 12). Fewer and fewer teens know how to drive. The median age for having a kid in the U.S. is now 30 — up from 21 in 1971 — which means that grandparents are also older, and may or may not be capable of handling regular interstitial care. Finding interstitial care was already incredibly difficult before the pandemic. Now it’s like competing in a decathlon.

Whatever you think about these changes matters far less than the societal reality we have created. School is set up as if every family has someone (paid or unpaid) capable of providing pickup and care before and after school, during school vacation times, and over summer break. For the millions upon millions of families for whom that is not the case, flex has to be found within the workday. Caregivers can do this sheepishly, shamefully, surreptitiously — or the workplace can acknowledge societal reality, and figure out a way to create the sort of flexibility that benefits everyone, not just people with childcare responsibilities.

Maybe a worker uses their “dead zone” to go on a walk. That’s fucking great. Maybe they use it to stare at a wall. Maybe they go golfing (the horror, the horror) or volunteer or hang out with an aging parent or do some deep focus work — or, you know, just not work. Maybe they shift that dead zone to the early morning. Whatever they’re doing is, in fact, none of the employer’s business, other than to understand that taking time away from work has the extra benefit of making you better at work when you’re actually working.

There is nothing “natural” about the workday. It should expand and compress according to the demands of society and the work itself — even if that sometimes means working in different configurations. But that is not the purpose of this Wall Street Journal article or its knockoff in Fortune, which earned the even more inflammatory headline of “Workers are creating a ‘dead zone’ between 4-6 p.m. to fit in COVID-era habits like school runs and gym sessions,” plus even more knockoff knockoffs in Business Insider, Forbes, CBS, and Yahoo Finance.

These articles are intended to hail and affirm business leaders who feel their power over workers’ time is eroding. The article can’t make up facts (as Finan and Bloom point out in their golf research, productivity remains steady, even post-pandemic!) but these pieces can voice grievances: that, in very certain instances, it’s hard to “huddle” on a problem that arises after 4 pm because some people are off, or that sometimes it takes several emails over the course of the evening to resolve an issue, or that after a full day of meetings you can’t cram even more meetings into the hours between 4 and 6 pm.

But let’s be very clear: those aren’t real problems. They’re problems with perspective — and indicative of an organizational structure that privileges the exceptional requests and convenience of those with power over the everyday needs of everyone else.

That might just sound like a workplace, but it also sounds like an unhealthy one: one where workers are less happy, where quit rates are higher, where burnout is a bigger problem, where it’s harder to excel or even just survive as a person with caregiving responsibilities, where having people scroll Twitter until their eyes burn because their brain can’t do anything creative is just “the way things are.”

But if that reality sounds like the actual problem, there’s an abundance of studies and writing and advice on how to grapple with those problems — including the first article that popped up in the “What To Read Next” feed at the bottom of that WSJ article.

The findings in this article were stunning. After an 18-month trial of a different way of working, conducted in the U.S., Canada, Ireland, and the U.K., employees reported less burnout, improved health, and more job satisfaction. Turnover decreased, and productivity held steady.

Amazing, revelatory stuff. What changed? They were tasked with working four days a week instead of five. They didn’t work ten-hour days. They didn’t lower the overall amount of work expected of them. They just held fewer meetings and concentrated more. And the longer they stuck with the four-day plan, the happier they became — again, with no drop-off in productivity.

There are always going to be people in business who want to read articles and listen to speakers that confirm hierarchies and frame change as rebellion, laziness, or both. To them, work is hard because work should be hard; if excelling requires ruthless negligence of the world around you, so be it.

And then there are people who observe the landscape of work and understand it as endlessly dynamic and malleable to change. For them, work is hard but there is no reason work has to be this hard — or hard in such arbitrary and omnivorous ways. They believe that work could be much easier, much better — in part by giving workers more agency, more trust, and more control.

The next time you see an article like the one discussed here, consider: Who, exactly, is engaging in the behavior — and how are they benefitting from it? If it’s a behavior that ultimately makes a type of work more equitable, more accessible, more sustainable, more survivable, then ask another question. Whose interest does it serve — and whose power does it protect — to understand this particular change in the way we work as a problem? ●

Further Reading:

SPEAKING OF WORK, we’re planning some new episodes of WORK APPROPRIATE and need your workplace quandaries for three upcoming episodes:

My Industry is Broken: Tech Edition (with the legendary Ifeoma Ozoma)

How to Deal with Your Org’s Broken/Pitiful/Contradictory DEI Efforts (finalizing co-host, stay tuned)

Your Truly Tricky Management Questions (as managee or manager) with my favorite no bullshit management advice giver, Melissa Nightingale. We’re going to try and stump her, so no matter how weird or toxic, ask away.

You can submit your quandary here — and as always, you can stay as anonymous as you’d like.

If you enjoyed that, if it made you think, if you *value* this work — consider subscribing:

Subscribing gives you access to the weekly discussion threads, which are so weirdly addictive, moving, and soothing. It’s also how you’ll get the Weekly Subscriber-Only Links Round-Up, including the Just Trust Me. Plus it’s a very simple way to show that you value the work that goes into creating this newsletter every week!

As always, if you are a contingent worker or un- or under-employed, just email and I’ll give you a free subscription, no questions asked. I do these in batches, so if you’ve recently emailed and haven’t heard back yet, I promise it’s coming. If you’d like to underwrite one of those subscriptions, you can donate one here.

If you’re reading this in your inbox, you can find a shareable version online here. You can follow me on Twitter here, and Instagram here — and you can always reach me at annehelenpetersen@gmail.com.

I love the practicality of this piece, but I believe there's a subtext at play as well, which is that for most of us, there's a natural energy dip in the late afternoon. I think even people without caregiver concerns find themselves less mentally alert in the 'dead zone.' The 9-5 (or 8-6) is just a construction from the industrial revolution when people NEEDED to be at a factory. But it has never matched most of our innate rhythms. I think that's why so many people are finding 4-6 to be an ideal time for other pursuits like working out (studies show peak performance occurs at 4pm for many athletes) or doing other, non-cerebral activities. How could things not improve in the workplace if we allowed employees to work WITH rather than against their natural periods of peak concentration? (With the added benefit of greater satisfaction, nervous system regulation and family needs met to boot?)

When I read that WSJ piece, it once again reminded me that so much of corporate America is stuck with the idea that the 9-5 construct is the only way to work. I freelance, so I’m here to get my teenager from one place to another, which is often at some point in the afternoon. When I worked in an office, the stress of getting home & making it to a school or sporting event was exhausting. The 9-5 construct has not been effective for a long time. Some people work best during non-traditional hours, and that should be widely accepted. Conversely, someone could be in the office from 9-5 and be completely ineffective.

Your point about how it was at Buzzfeed late in the day is similar to what it was like in a book publishing office during the same hours. Nothing got done because we were all exhausted!