Back in August, The 19th — one of my favorite new journalistic outlets, dedicated to intersectional feminism — called it. We are in the middle of the “First Female Recession”:

This year, female unemployment reached double digits for the first time since 1948, when the Bureau of Labor Statistics started tracking women’s joblessness. White women haven’t been such a small share of the population with a job since the late 1970s. And women of color, who are more likely to be sole breadwinners and low-income workers, are suffering acutely. The unemployment rate for Latinas was 15.3 percent in June. For Black women, it was 14 percent. For White men: 9 percent.

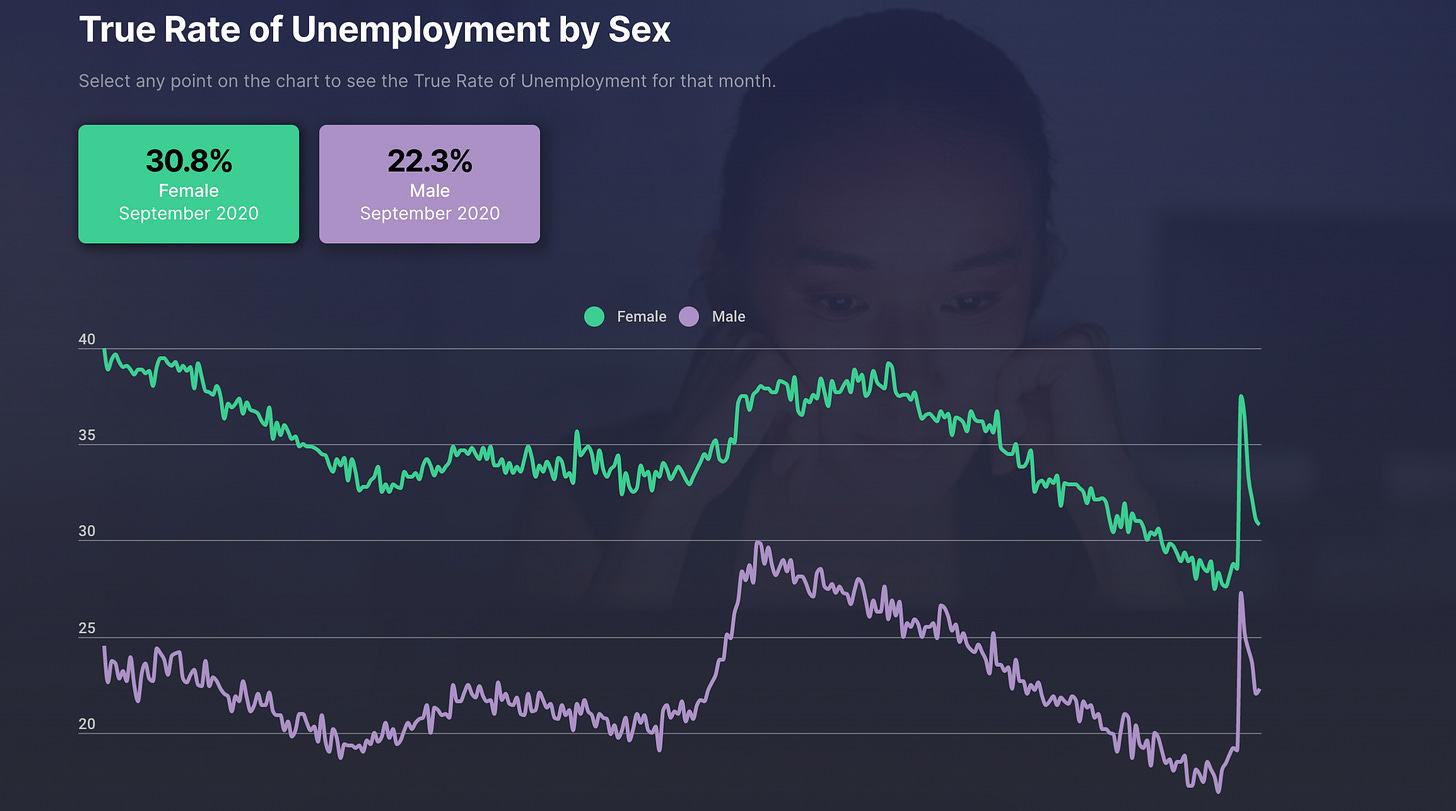

And that’s if you’re looking at strict “unemployment” numbers, which are pretty bullshit. As Felix Salmon pointed out earlier this week, “A person who is looking for a full-time job that pays a living wage — but who can't find one — is unemployed. If you accept that definition, the true unemployment rate in the U.S. is a stunning 26.1%.” The True Unemployment Rate for women: 30.8%.

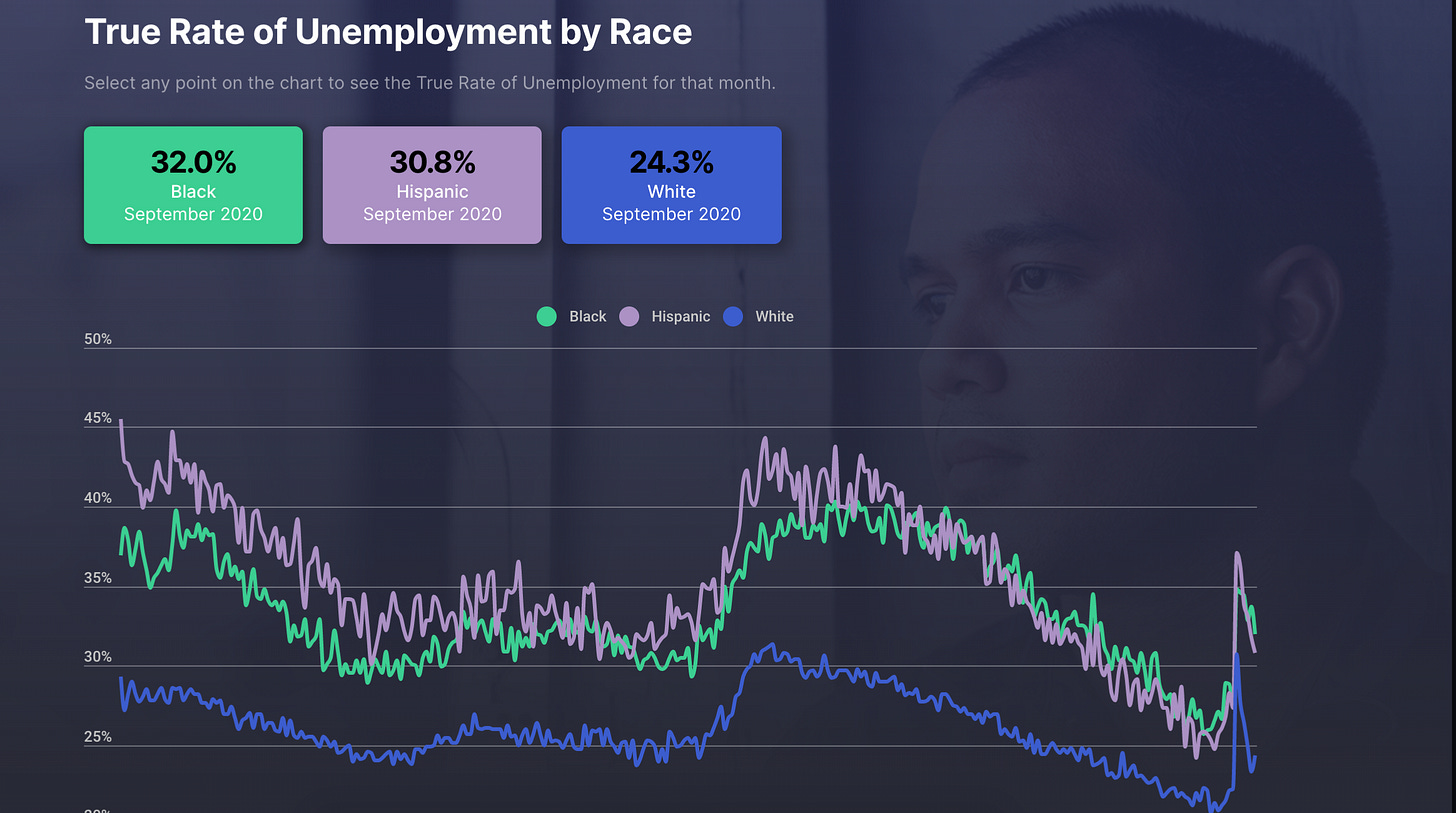

Unfortunately there’s no race *and* gender breakdown available, but you can see the True Rate of Employment by Race here:

Part of this has to do with layoffs in fields that employ a lot of women (while fields that employ a lot of men, like construction, are doing fine). And part of it has to do with women leaving their jobs. In September, about 865,000 women dropped out of the workforce — compared to 216,000 men.

Before the pandemic, women in the United States still made only 82.3 cents for every dollar men made. Even with the wage gap decreasing, it's still a significant gap — and when a household is faced with needing a full-time caregiver, it's the person who makes less (usually the woman) who quits her job.

In COVID times, it makes twisted sense: She was probably doing most of the home-school supervision anyway, even if her husband thought otherwise. She likely also carried the majority of the "mental load" — that is, the never-ending list of tasks that need to be completed for the family to function. In most of these cases, a woman isn't actually quitting work. She's just quitting the one of her jobs for which she was paid.

I started collecting stories from women who’ve either quit or significantly reduce their hours several weeks ago, and ended up writing a short piece for MSNBC (which I’ll be doing periodically going forward) about the ramifications of this move — and how it will exacerbate existing inequalities (not just related to gender) even further. But part of the reason I started this newsletter was to make space for some of the reporting — and detail of story — that doesn’t make its way into short pieces for mass consumption on major news sites.

Below, you’ll find women talking about their decisions. If your first impulse, upon reading these, is to say that there are some good men out there trying to mitigate these problem: of course there are some good men, and who knows, you might be one of them. But your existence does not obviate the stats, or this very real problem. (With that said: I do include a good feminist dad in the mix here!)

To be clear: all of these women are privileged (and acknowledge as much) even to have the decision of quitting or cutting back available to them. This is a particular slice of the demographic of women dropping out of the workforce, and I want to draw attention to what’s not here: women who simply do not have the option to quit; women who are working so hard that they have no time to respond to a reporter; women who were shut out of the workforce for myriad reasons pre-pandemic. Those stories matter too, and I’m going to keep working to figure out ways to tell them. (And if you’d like to tell me your story, I’d love to hear it.)

As I write in the MSNBC piece, these aren't personal problems or failures. They're societal ones that demand a societal response — including from those who aren't parents — that attempts to address the way we devalue women's work in and outside the home, the sustained labor imbalances in the heterosexual home, the way we support single parents and how race and location and class intersect with all of those things. This isn't a step back that can be easily regained. There will be no V-shaped recovery from the "first female recession." It will leave scars and deeper inequities that will endure for decades.

Desi, Age 43, Michigan

I’ve run my own online pattern business since 2010, which grew out of a blog I started back in 2007. I’m partnered and have three children (13, 11, and 6). My husband cofounded a company which brings in good but sporadic income: when things are good, he earns a salary, but when things slow down he doesn’t get a paycheck. This year he has had to take a pay cut and is worried soon there will be no company left. Normally my job can be anywhere from part to full time, is flexible, and it brings in additional income that adds stability to our family.

I didn’t have any childcare options for this fall that felt safe, and my husband couldn’t do part time at his job anymore. Most people aren’t taking the pandemic seriously and that has made finding a babysitter who can come into our house really difficult. I decided that it wasn’t worth the risk anymore so I’m staying home with them.

Now, I can’t work regular hours at all - I have to squeeze a few minutes of checking email and projects in here or there, my total work hours are less than 5 hours a week. It feels like I’m barely managing to keep my company together.

I feel unmoored and unhappy. I can’t work, which normally fulfills me, and I feel like I’m missing out on opportunities to use my sewing business to help connect people and help them feel grounded right now, let alone feel connected and grounded myself. Monitoring online school is not something I am good at. My youngest kid is 6, and online school is not working for him. He cries every day. My big kids are unhappy and miss their friends. Every day feels like a rollercoaster.

I am just so angry. Most of the time though I just want to cry. I desperately want to return to work. But when? Right now it feels like there is no end in sight. We should be advocating for protecting those who have the least. That is what a healthy society does. That is not what is happening here.

Kristen, Age 47, Bay Area, California

I’m a freelance book editor with two kids (15 and 12), divorced almost a decade ago and now in a long term relationship with a partner who works in tech. My partner and I share household expenses but otherwise (by choice) keep our finances separate.

I spent a few years living with my kids in a one-room studio apartment. But after five years of building my freelance business, I finally reached the point where I would’ve been able to afford half the rent of a 3-bedroom house with a home office. It felt stable – exciting even. I was tremendously proud of what I’d built.

When I faced up to the fact that my daughter, who was really struggling with online school, was unlikely to go back in person in the fall, I realized I needed to cut back my schedule. I stopped taking on new clients and even sent some returning clients to other editors. I stopped my weekly newsletter. I’ve stopped doing any kind of non-essential work on my business (website updates, quarterly expenses, training).

When my daughter’s school started up, I made a work space for both of us in our living room. I’ve done everything I can to make it cozy and fun. We have good snacks and afternoon tea every day. She is truly thriving and has come out of the dark place she was in during the spring and a big chunk of the summer. I am relieved and proud that I have done that for her. But it has profoundly changed the way I work. I don’t go more than 15 or 20 minutes without an interruption.

The minute I decided to have kids, my career choices were impacted in ways I didn’t fully understand. I chose to put my own career on hold when my kids were young, in part because my ex-husband’s job required a lot of travel and a lot of hours, and I couldn’t see a way to make it work. If I had had a different sort of marriage that might not have been the case. When women start out making less and maybe even choose fields that pay less or choose jobs that give them flexibility for having a family, then when the hard choices come it seems obvious that the person who is making less must be the one to step back.

But it was never a choice —that’s the thing I understand now. It was something I would have had to fight for every step of the way. And then I got divorced and was in a pretty bad place financially. When I couldn’t get hired, I made a job for myself. Now I’m just limping along.

I feel deeply sad. I know this is what needs to happen right now, and I’m grateful that I could dial back my business to do it. And after some period of rest and collapse I hope I’ll be able to start doing more things again. But I will have lost at least a year, and at 47 that doesn’t feel like a small thing when you are just moving from able to cover the basics to having healthy savings and retirement accounts and a real feeling of financial safety.

Kaitlin, Age 42, Portland, Oregon

We’re two queer parents to a 4.5 year old child. Before the pandemic, one of us had a well-paying operations job, and the other was in nonprofit fundraising — we were comfortable homeowners, but also living month to month, with expensive childcare, plus student and credit card debt from child-making and ectopic pregnancy bills. I would describe as as fairly comfortable and privileged, but with plenty of financial stress.

At the beginning of the pandemic, I took EFMLA leave, while my wife worked an immense amount of hours of home. We felt pent up, but had lots of lovely moments with family, too. But working form home and giving my 4 year old what they needed — while my wife worked 60+ hours a week — was simply not possible. We did a lot of brainstorming and budgeting during my leave and figured out that I could quit.

Despite my misgivings, my love of my job, and my fear of not working, I’ve slipped quit easily into full-on parenting, teaching, gardening and cooking. Our child’s outbursts have subsided greatly (but don’t worry, they’re still there). We know they need other time with children and I need income, so I’ll be watching two other kids in our unofficial backyard play school whose parents also didn’t feel comfortable with daycare.

As a society, we need employers to support families with children, we need direct aid to families, we need support for essential service workers, and we need a cultural shift so the burden of career disruption doesn’t affect women so much more. But as for us, we’re in a queer relationship, and the dynamics are different. My wife makes twice as much money as I do. That was the decider.

Erin, Age 36, Denver, Colorado

My life is completely different. Seven months ago, I was running 300+ person conferences for women in male-dominated industries. It was a job I’ve always dreamed of and I loved it so much. I quit knowing there’s no guarantees I’ll be able to return to the specific role I’ve loved so much.

It was an interesting juxtaposition, going from working full-time on issues like gender equity in the leadership pipeline and supporting women in male-dominated industries to staying at home with the kids and occupying a pretty traditional gender role. The first couple months were rough, as I’d never planned to or particularly wanted to occupy the role of a stay-at-home parent. It took a while (and a lot of therapy for me) to get into a rhythm that worked for all of us.

But now I’m finding that I really love the time with the kids. My husband and I traveled a lot before COVID and I don’t think I realized it was possible to not constantly be juggling several urgent work/home emergencies all the time. Now that I’m used to a slower pace, I find I don’t miss the frenetic lifestyle we had. I really miss studying the nuance of women’s leadership, but I never really had the opportunity to focus solely on the topic — I was always living it, too, running from my kids’ specialist appointments to strategy meetings, etc.

I will always work in some capacity; I love having a piece of myself outside of my role as a mom, wife, etc. But recently, we’ve discussed the possibility of me working part-time. With our 4 year-old’s asthma, seasonal kids viruses, an anaphylactic allergic response, pneumonia on Christmas, and our toddler’s hospital stay for a respiratory illness, we had over 20 doctor’s appointments/specialist appointments/hospital visits over three months while we were both working full-time and traveling. That’s just not sustainable.

I felt guilty about going from women’s professional leadership to staying at home full-time- like I was letting other women down. But we live in an environment that supports working men a lot more than it supports working women. None of the women I know who have decided to stay home instead of their spouses did so in order to follow traditional gender roles. They do it because they can’t support their family on their own income, whereas the husband can. Even when their education, work experience, etc. is the same, the husband makes more. We need legislation that supports women better: universal childcare, and better maternity leave.

Jason, 40, Chicago

I'm 40 years old, and before I left my job at the start of this school year, was a K-12 teacher. My partner is a 37-year-old attorney and we have two kids, daughters, 5 and 2. We have plenty of student loan and credit card debt, but are otherwise pretty financially secure.

The end of last school year was difficult: my wife had just started a new job, and we were both working remotely in the house with the kids. We limped into summer break, at which point my wife’s employer had run out of patience and understanding for COVID-related drains on productivity. It didn't seem possible to send our 2-year-old to day care, our now-5-year-old to school, for me to go to school to teach myself, and have my wife dedicated completely to working from home without interruption, knowing that at any time a quarantine situation at school or day care could destroy the whole delicate balance.

Part of this equation was that I taught at a private school, one that was insisting on in-person instruction in the Fall. Rather than chancing it when it came to safety and logistics, or making the ethically and financially questionable decision of hiring a nanny to just take care of the kids, we decided that the best option would be for me to stay home with the kids this year.

Approaching decisions from a feminist perspective has been a recurring consideration throughout our relationship. Knowing that my wife had twice put her own career on pause — taking extended breaks from work to have children and go on leave, and also dropping down to part-time work to help facilitate our child-care dance when our kids were even younger — was a real consideration in our discussion. She also makes significantly more money than I do, so this helped make our choice a practical possibility.

Having made the decision to center our family's health and safety has felt like a huge victory, and the right decision — and exerting control over our lives in this way has been emotionally healthy as well, amidst ongoing national chaos. But I’m so angry that all of this, especially the more than 200,000 people who’ve died, was preventable.

Sarah, New York City, 35

My husband and I have two kids: a boy, who’s five and is autistic, and a girl who just turned four. My husband is a teacher with many years in the system, and I hand landed a good, well-paying part-time job in research/comms for a non-profit that offered me flexibility. We had great childcare three times a week, and our son was in full-time school. It was hectic but we had a groove.

In June, they shut my program down entirely. Because my husband is a teacher and I wasn’t working, we were able to do a ton of stuff: lots of camping, beach days, small trips, zoo visits. It was intense and hard and sad, but it was also fun a lot of the time, and I got to see a lot of growth in my kids.

But as soon as we figured out how wonky school would be, we decided I shouldn’t look for work. Between managing our son’s in-school session and remote learning for both kids, it didn’t feel feasible for me to do anything else, or to ask a childcare provider to navigate those processes.

In a lot of ways, our life feels better: I’m on top of stuff and am able to focus on keeping things at home going. Responsibilities are definitely shifting back to me in ways that feel reminiscent of when the kids were first born; I’m handling basically everything for school, doctors appointments, most of the cleaning, etc. My husband helps a ton: he does most of the cooking, a lot of the everyday housework things like taking out trash, and is an active parent when he’s home. But I’m becoming the primary holder of all of these things again, which both makes it simpler and is exhausting.

I’m pretty sad about my job, and that I had reached a place where I was being adequately paid for my work and recognized for my expertise and that’s disappeared and will be hard to find again. It was a relief in the context of the pandemic - we were having a really hard time balancing and I felt like my head was spinning a lot of the time.

But I feel sort of bewildered by the fact that I’m a bright, competent woman who is very concerned with equity, and that I and a lot of women I know like me are ending up in the same place, agreeing to replicate gender roles we wanted to move away from. These are decisions my husband and I made together and they make the most sense. But I also feel the weight of all my lost potential and the lost potential of the women I know. ●

If you know someone who’d enjoy this sort of thing in their inbox, please forward it their way. If you’re able, think about going to the paid version of the newsletter — one of the perks = weirdly fun/interesting/generative discussion threads, just for subscribers, every week, which are thus far still one of the good places on the internet. If you are a contingent worker or un- or under-employed, just email and I’ll give you a free subscription, no questions asked. If you’d like to underwrite one of those subscriptions, you can donate one here.

You can find a shareable version online here. You can follow me on Twitter here, and Instagram here. Feel free to comment below — and you can always reach me at annehelenpetersen@gmail.com.

Somehow we need to work backwards from a decision made by clear-eyed partners that says the woman should quit her job and see where girls and young women and moms make the choices that end up with them making less, working fewer hours, and being more competent at parenting the children. It is tough for a mom to insist that she needs to work outside the home, even if it means getting by (hopefully) on less. But maybe she should.

From my vantage point of 60+ years, regretting some of my early choices, I know that I enjoyed many of the moments I spent staying home with my kids and regret so much the vibrant career I never had. I got a job (part-time!) which I hustled into a full time job (very low paid!) after my husband walked out on me, but it was never really a career, as much as I tried to make it one.

One thing I know is important is mentors and examples. My dad told me that I was going to grow up to be a mommy. Neither he or my mom asked me what I wanted to be. I did not know a single mom when I was growing up who worked outside the home. I didn't know anyone at my church who did, either. My advisor in college, a man, had no other women advisees, never asked me about what I was going to do when I graduated, even as I continued to excel. Get this: when I started dating a pre-med and wasn't sure what to do with my major (chem), I added a teaching certificate to my schedule "so I could have the summers when my kids were off." Even as I type that, I gag.

Thank you so much for writing this. These are the kinds of stories I’m hearing and seeing and living - and it’s so wonderful to not feel alone in both the exhaustion and anger.