This is the weekend edition of Culture Study — the newsletter from Anne Helen Petersen, which you can read about here. If you like it and want more like it in your inbox, consider subscribing.

This piece is an experiment. I’ve been wanting to write a long feature on the various components of Peloton for more than a year — and have repeatedly found myself intimidated by the scope. Like a lot of deceptively complicated media texts, it deserves a book. But a book of Peloton analysis is not happening. This newsletter-bound serialized analysis is.

Over the next few months, I’ll be exploring, analyzing, and tying together the different components of Peloton, from its deployment of a studio system-style star system to its rhetoric of the body. Instead of approaching this series as supports for a concrete, overarching argument, I’m thinking of it as a series of pieces building toward a theory of why Peloton, and why now? What does Peloton reflect about our current moment — and what ideas (about fitness, about lifestyle, about consumption) is it challenging or solidifying?

Why analyze an expensive piece of equipment used by 4.4 million people? Because, as any Peloton user will tell you, it’s much more than a bike. That sounds lame, but it’s really a way of saying that it’s serving a much more potent ideological function than “just a new exercise fad.” Some aspects of what Peloton is doing are not at all new, and some, like the parasocial relationships with individual fitness instructors, combine the previous blueprint for celebrity fitness with the prolonged digital intimacy and “authenticity” of influencer culture.

The company is particularly skilled at cloaking what is, in fact, just a bike (or just a (recalled) treadmill, or just an app) in the language of lifestyle — a shortcut, of sorts, to personality, particularly appealing to the sort of bourgeois consumer whose work and parenting commitments have subsumed the corners of their lives where personality was once cultivated. It offers immediate, instant access to exercise, purposefully malleable to the user’s schedule.

And unlike, say, pilates DVDs or self-directed push-up routines, it’s endlessly dynamic and incredibly adaptable to the individual’s fitness needs or goals. You can use Peloton to get the same workout you would get while doing the elliptical on low resistance while watching HGTV, or you can get in the best shape of your life — by yourself, in your living room or the sliver of space next to your bed, surrounded by the aura of community, but not the inconvenience of it.

Again, we’ll be exploring these ideas, plus a lot more, in the months to come. I also want to clarify that I have a Peloton, and I love it, and like all objects and celebrities and texts I love, I want to analyze both the thing and my attraction to it. I’ll be interviewing fitness historians, talking to branding and PR management people, thinking more about the way that fitness has replaced more traditional spiritual and community involvement, and consider the lightly dystopian trajectory of communal spaces (like gyms, and running trails, and public lands) shifting into individual homes. And if you have areas of the text you’d like to see explored, tell me about them in the comments.

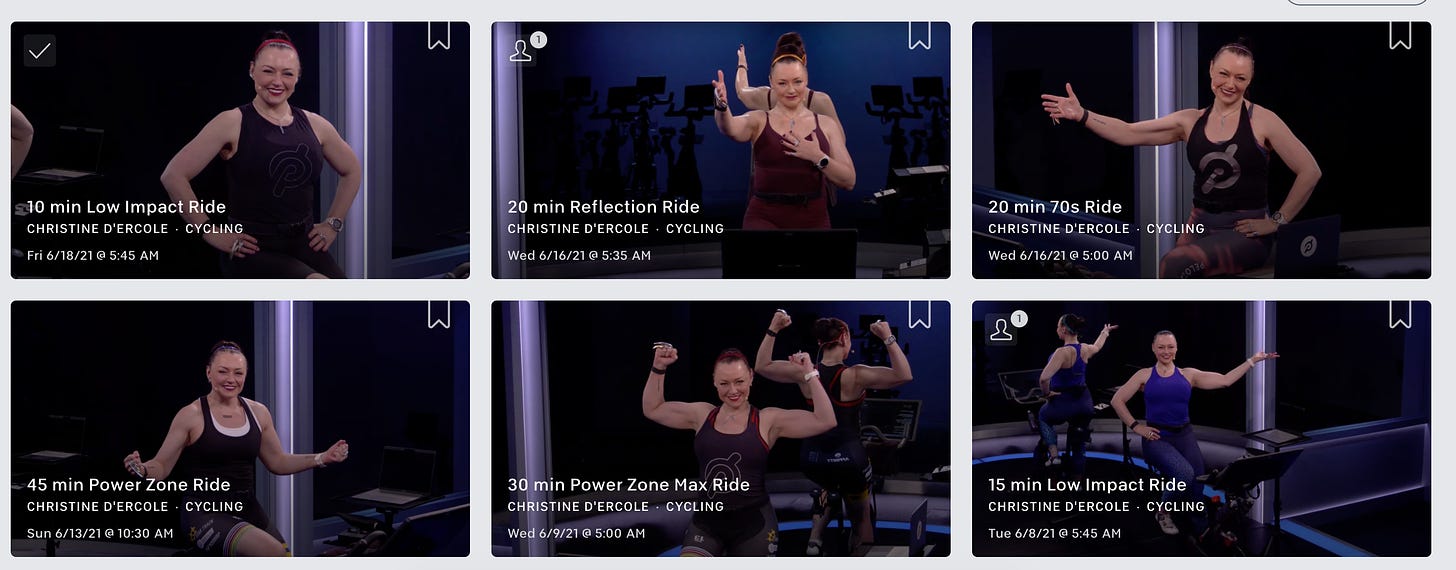

But for now, I want to talk about the stars. Without them, there is no Peloton. They are tremendously valuable and, at least within the Peloton universal, meticulously individualized. Jess King is a rave kid. Alex Toussaint is the drill sergeant. Robin Arzón gives you type-A tough love. Ben Alldis is a Ken Doll. Emma Lovewell just wants to chill. Ally Love is giving the youth sermon. Sam Yo is the buff ex-Buddhist monk. Christine D’Ercole is the Gen-Xer who wants to release you from your own bullshit. Cody is the gay friend. Denis is the Silver Fox. Jenn Sherman is Mom.

If those sound reductive, they’re meant to be. They’re not full-fledged personalities, they’re image foundations, carefully cultivated by Peloton and the instructor themselves. As with all stars, whether or not they’re reflections of the “real” person is inconsequential. Their image is their vibe, their style of teaching, their self-presentation, and, ultimately, the way they mean.

When someone says “I really need a Cody ride” or “I really need an Alex ride,” they are communicating a craving for a mode of address. Do you want someone with a very normy vibe to give you vaguely Dad-ish platitudes about endurance fitness? Take a Matt class. Do you want to curse at your tiny instructor? Choose Olivia. Do you want to want just broadly feel good about your life choices? Take Jess Sims. Some of what Mandy Harris Williams calls “athletic blackface”? You’ve got, well, options.

Many instructors come from the fitness world, and many were poached from places like SoulCycle, where a cult of personality had already formed around their particular teaching style and image. The forgettable fitness instructor you kinda like has no place at Peloton. They sought out charisma.

Which is why a significant portion of the fitness stable comes from the dance world. Ally Love, Emma Lovewell, Jess King, Cody Rigsby — all dancers. Their rides are, ultimately, choreography. The fitness is secondary to the performance of fitness leadership — the combination of instruction, encouragement, repartee. Cody distracts. Ally focuses. Emma calms. Jess King does Jess King.

Peloton has worked hard to distinguish each instructor’s image and style from the others, even when they have the same (very millennial) names (two Hannahs, two Jess-es). They have also recruited in a way that I would describe as “always be able to have at least two instructors represent a [INSERT IDENTITY CELEBRATION HERE] month.”

They are aggressively conscious of racial representation — both in terms of their own marketing (particularly on their Instagram, which is something I’ll address in future posts) and the literal faces of the brand. But that diversity is still limited to bodies and gender performance that align with the mainstream status quo. Instructors never talk about weight gain or loss, just power and listening to your body — yet there’s clearly an ideal Peloton body, and that body slender and muscled, with slight variation for some of the older women instructors (who are given passes on the high waisted yoga pants + sports bra uniform required of the instructors in their 20s and 30s).

None of this might seem that different from how a group of celebrities come together for a product, a movie franchise, a team, or a cause. But this isn’t The Avengers or the Lakers. Outside of niche New York fitness communities, none of these instructors were even known names five years ago. The company has effectively created a stable of global stars, softly controlling their public-facing images in a way that recalls the classic Hollywood studio system, the Mickey Mouse Club, teen music group “factories” like Trans Continental (responsible for the Backstreet Boys + N*Sync), and, in a slightly different form, TikTok houses.

Peloton helps its instructors shape their brand, both in terms of their textual persona (what sort of workout they provide; their catchphrase + hashtag; costuming) and their extra-textual persona (Peloton photography, which exists in abundance; Instagram; traditional PR). The company largely controls the costuming (mostly Peloton gear, with new fashions introduced each season to incentivize new purchases), the styling (Tunde does her own makeup; other instructors collaborate with the styling team), and, depending on the type of ride, components of the messaging (see especially: the clumsily scripted Artist Series rides).

Historically, one of the primary differences between traditional film stardom and television stardom was the feeling of grandeur: that they were nothing like us, essentially demi-gods, their faces, in close-up, as tall as a movie screen. Television stars, by contrast, were consumed in your home, far smaller than life — less glamour, more domestic, more “just like us.” Expand that framework a little more, and you’ll find the relatability and disposability of YouTube stars and influencers, consumed on the phone, and largely indistinguishable from the larger Instagram feed of friends and family.

Peloton stars, at home on the extra large tablet, occupy a slightly different space. While reality stars, influencers, and YouTubers float across our vision, passively consumed, often while multi-tasking, a Peloton instructor has your full attention. You’ve shown them your worst and best self. They’ve piloted you through frankly melodramatic episodes of athletic exertion. They might not know it, but that doesn’t mean you haven’t experienced it while staring directly at their faces. They’ve asked you questions and you’ve answered, even if they haven’t heard those answers. During the pandemic, I spent more time with Peloton instructors than anyone other than my partner. There’s something there.

And that something is maintained through the continued cultivation of intimacy. Instructors talk about their pre-Peloton lives, their upbringings, their memories — the sort of small talk that, spread over hours upon hours of time on the bike, fosters a real sense of intimacy. They get weird (Denis) or spiritual (Ally), talk about racial privilege and accountability (Tunde), and create scenarios ripe for a little on-bike crying (Christine).

Do I think that Alex’s in-class discussions of Black Lives Matter and what it’s like to navigate the world as a Black man were of his own divising? Absolutely. But this is also a company that clearly discouraged its instructors from even saying the word pandemic. That discussion was green-lit. Same for Ally’s explicit religious invocations, which eventually became Sundays with Love. They’re not scripted. But there’s some messaging management going on, even if it’s working hard to stay invisible.

Apart from the primary text of the Peloton classes, all instructors broadcast their “real” lives — first and foremost on Instagram, with small, secondary doses provided via of traditional celebrity profiling (Robin in Shape; Cody in Vogue; Sam Yo in People, Emma Lovewell in Rue, etc etc). I don’t think Peloton runs the instructors’ Instagram presences. But you can see evidence of, well, coaching.

There’s no tacky endorsement deals, just partnerships with other (on-brand) brands (Cody with Chobani, Matt with Nuun, Chelsea with Estee Lauder, Alex with whatever weird contraption essentially functions as massage pants). Emma Lovewell did a commercial for Miracle-Gro lawn care — but she was in “character” (aka, in plank) the entire time, and it was for the Super Bowl.

Whenever one of them posts an announcement to Instagram — or, for that matter, any sort of comment — at least a half dozen of the others reply, even if only with an emoji. There are well-photographed group events, which contribute to the overarching feeling of a “Peloton family” (of which you, as a user, are an extended part). “Athletes” (aka, users) are explicitly represented in that universe when coaches repost Instagram stories, or go live on Instagram before or after classes to make space for the “shout-outs” that have become harder and harder to get during Live classes. It feels good, somehow, to hear your username come out of your teacher’s mouth.

Other instructors periodically share corners of their domestic lives (Emma’s farmhouse renovation, Alex’s newly purchased Jersey spread, Ally’s engagement, Selena’s engagement) but they’re highly sculpted and thematically unified. Robin announced her pregnancy in a special occasion ride — and the Peloton main account posted the first baby photos. This isn’t just a company congrats. This is a symbiotic relationship between company and personal brands.

The company is forging a relationship between you and an activity, glued together by the parasocial relationship with the instructors. The charisma and connection allows the user to forget — or maybe just embrace or narrativize — the investment required to participate. Again, this isn’t novel to Peloton — it’s the bond at the very heart of the entertainment industry! — but few celebrity industries require an investment quite as extensive and ongoing.

What happens when Peloton stars become too powerful? It’s already clear that many of the senior instructors have, uh, leveled up. Unlike classic Hollywood stars, they have company equity. But what’s the ceiling? Two instructors have left the company — which, interestingly, has led to a complete scrubbing of their presence from the site and the class library. That was pre-pandemic, however, and pre-membership-surge; ripples didn’t become waves, outside the very active Peloton Reddit threads. Post-Peloton instructors could easily land a lucrative set of personal trainer gigs. But could they ever get the partnerships or sustain the engagement that accompanies long term intimate presence in a bunch of upwardly mobile users’ lives?

MGM made Elizabeth Taylor, but Elizabeth Taylor didn’t need MGM. Her magnetism was far more the sum of the studio’s publicity acumen. There are stand-outs amidst Peloton’s star stable, and all of them are fundamental to the larger pull of the brand. But the real star — the product that keeps people coming back — is, to be incredibly cheesy, found in the user. It’s how you fucking feel. The instructors are a big part of that, but they’re also readily replaceable with similar types. So how else does Peloton cultivate that feel — and keep users addicted to it? That’s for the next edition.

If you read this newsletter and value it, consider going to the paid version. From here on out, the weekly “Things I Read and Loved,” including the “Just Trust Me,” only go out to Paid Subscribers.

One of the perks = weirdly fun/interesting/generative discussion threads, just for subscribers, every week. The other perk: Sidechannel. Read more about it here. There’s a new, private, subscriber-only channel for job hunting that is already transforming resumes.

If you are a contingent worker or un- or under-employed, just email and I’ll give you a free subscription, no questions asked. If you’d like to underwrite one of those subscriptions, you can donate one here.

If you’re reading this in your inbox, you can find a shareable version online here. You can follow me on Twitter here, and Instagram here. Feel free to comment below — and you can always reach me at annehelenpetersen@gmail.com.

I've always had a hypothesis about the physical/mental dynamic of the Peloton experience, and how it becomes addicting: you have a very attractive instructor looking directly at you, telling you how good you are, while you're washing your brain in endorphins. There's got to be something there.

The first time I was aware of PC was at the mega-Methodist church in Kansas City where the pastor devoted part of his sermon to his friend, who is well known in Peloton World. But this friend is not an instructor -- he's a participant who is very expressive about how much he enjoys riding his Peloton. And he's known for having >> lost a bunch of weight << on Peloton. and gets joy out of riding. Take out the weight loss story, and he's just a goober in the background.

I find it almost impossible to express the joy I feel in running, so I don't. I also don't talk about my times or how it keeps my weight artificially low. Yesterday I ran with a running club for the first time in over a year, a group I hadn't run with before. Lots of older runners, another grandpa, a woman going through a divorce. We ran and yakked for 90 minutes and it was so pleasant because it had no structure no glamor and no purpose other than running -- an activity that was very important to each of us for reasons we did not advertise.