AHP note: This is the December Edition of the Culture Study Guest Interview series. I interview people nearly every week for this newsletter, but my inclinations and passions are, well, my own. If you have a pitch for an interview with someone who is not famous but writes or does work on something that’s really interesting, send it to me at annehelenpetersen @ gmail dot com. Pitches should include why you want to interview the person, 4-5 potential questions, the degree of certainty that you could get the subject to agree to the interview, and have CULTURE STUDY GUEST INTERVIEW in the subject line. Pay is $500.

This month’s interview with DL Mayfield is conducted by Christine Greenwald, who you can learn more about at the end of the piece. You can read previous Culture Study interviews on antiquities smuggling, on music as torture, on the social lab of PE — or just scroll back in the archives.

How do you live a life of compassion towards others in the midst of a world designed to recklessly extract profit with disregard for the well-being of its global citizens, most particularly the least of these? If you are part of a faith tradition, does that tradition work against or in support of treating all others with dignity and respect? And what do you do when the classic teachings of your tradition say one thing, but the actual institutions behave in quite a different way?

These are questions both Catholic anarchist Dorothy Day and writer and activist DL Mayfield have wrestled with. They belonged to different strands of Christianity, but each used the power of written words and the bonds of neighborliness to try to bring justice to the marginalized and oppressed. They were also relentless in calling their faith traditions to task for the ways they failed to live up to the values they claimed to hold.

They believed that if you just kept reminding the religious institutions what they supposedly believed and presented them with enough evidence about how they were not fulfilling those beliefs, the institutions would change. And while hoping for change, they were compulsive about living lives oriented to service and justice.

For Dorothy Day, she founded the Catholic Worker newspaper and houses of hospitality.

The longevity and zeal with which she devoted herself to her causes is nothing short of astounding. I suppose, of course, this is why she is in the process of being canonized as a saint. But it also raises the question of what is sustainable, and how “ordinary” people are to respond to the pressing questions of our time if we don’t possess the stamina, the self-sacrificial nature, or just plain desire to be a saint.

DL Mayfield knows how it feels to have an urgent, compulsive need to be a very good religious person and devote all of oneself to righting the wrongs of injustice. She spent years being the best evangelical possible, and then years after that passionately, loudly decrying the ways that evangelicalism has lost its way and trying to redirect it to the path of Jesus. Then she eventually realized that maybe the reason her faith group wasn’t listening was not because they hadn’t gotten the memo, but because they simply had zero interest in changing. And finally, she got REALLY DAMN EXHAUSTED.

Exhaustion and burnout suck, but they also play a vital role in bringing people from saintly or superhuman back to regular human level. What is sustainable for us, and how do we honor our own needs while not closing our eyes and ears to the rest of the world? What roles do saintly figures play in our life? Do we name people as saints and heroes so we have role models to follow? Or is it just so we feel better that someone is doing the work to make this world better?

Mayfield wrestles with questions around injustice, faith, social action, and saintliness in her biography on Dorothy Day, Unruly Saint, released last month. Mayfield also has her own Substack where she writes in raw and honest ways about the challenges and traumas of being autistic, emerging from high-control religion, and the unraveling of identity.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

CG: I imagine many people might be familiar with the name Dorothy Day, but would you mind filling us in a bit about who this "unruly saint" Dorothy Day was and what she did with her life?

DM: Dorothy Day is probably one of the most famous leftist Catholics in American history. Dorothy is in the process of being canonized in the Catholic Church. So, she’s a big deal in the institution but she’s also a beloved, known historical figure in New York City proper. That’s where she lived and started her Catholic Worker houses of hospitality, and there are still Catholic Worker houses in New York. She started a radical Catholic leftist newspaper in 1933, and it’s still passed out to this day. She was really obsessed with labor issues. She believed the Catholic faith offered solutions to societal problems through its basic tenements like the inherent dignity of every person and embodied works of mercy: If someone’s hungry you should give them food, if someone doesn’t have clothes you should give them your coat, if someone doesn’t have housing you should give them housing. Most of the Catholics she knew were just using their religion to over spiritualize the suffering of the world and not actually engage with it.

I finished your book, loved your book. In it, you talk about how in the canonization process they’re just really trying to flatten Dorothy Day in many ways and not acknowledge this radical leftist side, the ties with communism. Do you have thoughts about that?

It’s hard as a Protestant, because I technically don’t have opinions on her being canonized since I’m not Catholic. People come out on all sides about canonization. I think it’s good if it gets people reading her writings, because you can’t escape her radicalism in her writings, especially her early writings. That’s what I focused on in my book — sort of as a counternarrative to these extremely right wing, prominent Catholics, like New York archbishop Cardinal Timothy Dolan. They see Dorothy as an important person to have on their side in the culture wars against homosexuality and abortion. It’s really devastating to me to see her summed up that way. She herself was a radical, she loved leftists, she loved socialists, and continued to love them after converting to Catholicism. Her leftist radicalism is a throughline in her life, as is her Catholicism. There isn’t this neat before-and-after conversion story. But that’s how the Catholic church hierarchy seems to want to say is how it went.

It seems like there’s not too many people in that intersection of people who are super pious but also super radical, and it can make both sides really uncomfortable.

As the canonization process heats up, conservative folks will only emphasize Day’s piety and how she liked to pray and help the poor, and not emphasize her radical beliefs. Lots of people like to claim her – even people who are Christian socialists. I’m a little uncomfortable with that too, because she was mainly comfortable calling herself a Catholic and an anarchist. I wanted to take Christian anarchism seriously because I don’t see that talked about much. It’s worth studying and diving into.

Would you mind unpacking that: “Christian anarchism”?

For Dorothy, Christian anarchism is tied to the belief in the inherent dignity of every person and that every person should have autonomy. In a society, the people most impacted by oppression and who were the most marginalized would be in charge of determining their fate and their future.

She had a problem with socialists saying everything will be fixed by the state if we can just get these things passed. She was pretty wary of things like the New Deal – she called it this obsession with the Holy Mother State. She did not want to concede her personal power or ethical power to the state, because power always corrupts. She was not a fan of welfare reforms, because we should be taking care of each other. Our society should not be treating people the way they do. But at the same time, as soon as these welfare reforms were passed, she was getting people signed up, because she wanted to help people. But for her it was a personal ethical decision like ‘I’m not going to put all my trust in this state.’ And anarchism was how she did that.

Another example: before she converted to Catholicism, Day joined the women’s suffrage movement. She was arrested for protesting outside the White House for white women’s right to vote. She was brutalized by the police, had this incredibly difficult hunger strike, and experienced all this pain and suffering. But she herself never voted – like ever! She was an anarchist and didn’t believe in voting. And at first blush that’s really offensive to people, but she was right in so many ways. Because what we have in the United States is almost like a fake bourgeois democracy. It only works for some people. Only some people have the right to vote. When white women got the right to vote, it would be decades later before Black men had the right to vote and decades before Black women could vote. She questioned what was the point in voting when so many people didn’t have the same right. It was baptizing this really oppressive system and saying ‘yes it does work, we have a great democracy.’ But no, we don’t have a functioning democracy.

Speaking of her era, you noticed at some point there’s a lot of parallels between the society she lived in founding the Catholic Worker movement and now.

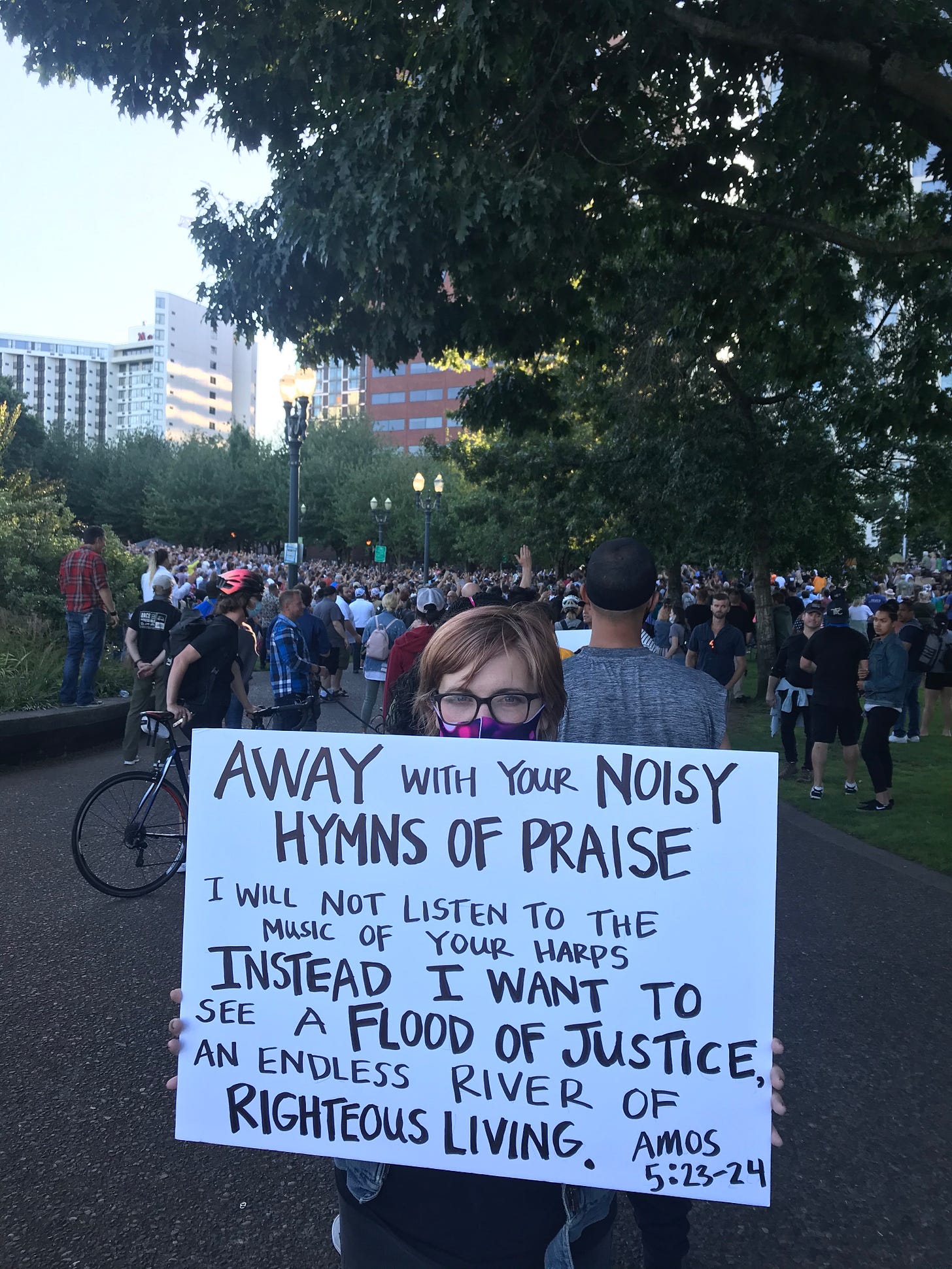

I signed the book contract in March 2020, so it was a really easy time to immerse myself in the birth of this movement in 1933. Covid was taking over our country as my own faith community — white evangelicals — was making the headlines for every bad thing possible. I was living in Portland participating in Black Lives Matter protests, the wildfires were burning… it felt like the world was falling apart.

We are currently dealing with Christian Nationalism, religious-based fascism, and this pull towards authoritarianism that privileges and prioritizes certain groups of people, mainly white Christians. That felt very relevant and was definitely happening in 1933. It was fascinating to learn about religious fascism and everything happening in Italy and how it was trickling to the US, along with antisemitism.

At the turn of the century, everyone was so excited: like things are going to get better and better, we’re never going to have a war again, the workers are going to get all their rights! And then WWI happened and shattered everyone’s perception that things are going to keep getting better. So many millions of people died, and for what?

Then there was the Spanish Influenza of 1918. Day actually worked as a nurse in the hospital in the front lines with people dying. She was involved in a pandemic, so all that was very fascinating to me. And then, of course, the Great Depression, and this explosion of inequality and suffering and visible poverty. Day lived in NYC on the Lower East Side and saw the lines of men begging for bread, for work, for housing. By that point, she’d become a Catholic and she wondered, what am I doing here? How can I be involved in helping all these people? Our economy, our society, is so unequal, it is so unjust.

In my city of Portland, the rents are rising so fast every year, nobody’s wages are going up, everybody’s struggling right now with grocery costs. Things are really bad and really hard, and I’m asking myself the same question Day did: If I’m a person of faith, what am I supposed to do right now? There’s so much suffering in the world; what am I supposed to do? Hopefully people can read about her life and come away with all kinds of takeaways about what they can do in this historic moment in our own history.

Yeah, so that question of “what can we do?” is a really complex one. But it makes me think, she’s this exemplar of giving it all, giving everything she has – literally and metaphorically – to the cause. There’s a tension between such devotion but also burning out and sacrificing too much (maybe especially for people who were raised religious).

I think that’s a big topic, but one of the hallmarks of the Catholic Worker was voluntary poverty. So that’s already assuming it’s privileged people coming into these spaces to live in solidarity with the poor. You choose to give up your lifestyle. Day came from a lower middle class, white Episcopalian family, trying to live in solidarity, thinking maybe that will help things, maybe that will make me a good person. I’ve struggled with that in the past too. I experience religious OCD, existential OCD, scrupulosity: where your brain gets stuck on these thoughts like ‘I must save the world, I must do this to be a good person.’ When I look at the saints I can see that too. I can see a bit of this in Day’s life. She wrote sometimes about getting an attack of the scruples – that’s literal scrupulosity.

And I think as Day’s being held up as a saint and exemplary figure, it’s like we just need a few extraordinary people, usually women, who give everything they have and they make us feel better because THEY are serving the poor, they are writing about issues of labor and unions, they are getting arrested by the US government. And we can feel better like yes, there is a person doing this work – we put them on a pedestal. And it can cause us to not engage in the ways we need to.

But for Day, she was obsessed with her neighborhood. And if you get obsessed with your place you will find inequality. You will find marginalized groups who have been doing the work for equality that you can partner with and join.

And personal autonomy is really important to anarchists. The better you know yourself, the better you know your gifts and your limitations. It’s not selfish to know who you are and know your limits. It’ll actually help the movement work. It’ll help our struggle for justice if you know what you can do and if you can commit to that wholeheartedly. And that’s not really a message we always get from people.

In my book, I point out how she co-founded the movement with Peter Maurin, who was this French, hobo philosopher who had this encyclopedic knowledge of Catholic social teaching and Catholic social history. And he was just adamant that if they told all the parish churches in NYC who had housing for priests that it wasn’t being utilized, so that wasn't in line with Catholic social teaching. They should convert their housing for priests into housing for men in the bread lines. And Peter was convinced the Catholic church was going to say yes. Dorothy was uncertain but willing to try it. So they went and asked, and surprise, no parishes did that. Peter kept trying to convince them, because that was technically what they believed, so he thought they should act in line with their beliefs. Dorothy got tired of waiting, and she pawned her typewriter to keep putting out the paper and rent the apartment and keep housing people. But literally, it’s a failure of institutions and systems to actually live up to their stated values to care for people. That’s the story of the Catholic Worker — the failure of institutions to take care of people.

Meanwhile, my faith community of origin does not have a single meaningful response to the issues of the day. That’s how I feel, if I’m being perfectly honest. There’s such loneliness inherent in that feeling. Because I still am a person of faith, and I do believe that Jesus and the ethics put forth by Jesus are just an amazing way to live life, one that prioritizes the most marginalized. And yet my faith community, who claims to believe in him, lives the exact opposite. Dorothy’s experiences really resonate with me — the inherent sadness of being a person of faith and being involved in justice work right now.

You currently write a Substack centered on late-diagnosed autism and how that intersects with a "special interest" [autistic trait] in religion and God, including recovery from religious trauma, for those who are coming out of high-control religion. First, can you help readers understand a much broader definition of autism and why late-diagnosed autism specifically is important to understand?

It’s not really all that complicated — it’s just your brain processes information in a different way, and you have a highly sensitive nervous system. So there’s a whole generation of people my age [38], usually women or people who aren’t white middle class boys, who have been missed for diagnosis. There’s a lot of people just now understanding it’s not just that they have an anxiety disorder, get panic attacks, are depressed, are obsessed with these one or two things in their life, and don’t have friends. It’s that they’re autistic. Now they can move forward with more self-awareness and self-knowledge.

It’s funny, as I was finishing up writing this book on Dorothy Day I started therapy for the first time and was actually diagnosed autistic. Up until that point I’d really identified with parts of Dorothy Day; I wanted to be like her; I wanted to be like Jesus; I went to Bible college; I wanted to be a missionary. I was all in. My perception of myself was as a hyper religious person, and that’s just who I was. Being diagnosed as autistic, it allowed me to step outside myself and say, oh, being hyper religious is a way I made sense of a really overwhelming and overstimulating world for me. I am someone who is drawn to black and white thinking, rigid thinking. High control religion like white evangelicalism does give you a semblance of safety if you’re a really anxious person like myself.

I was able to mask and was considered high functioning partly because I was all in on religion, which helped to mask some of my symptoms. One part of being autistic is you have these repetitive and restricted interests. Culturally we’re starting to see that in people who are big tech nerds like in Silicon Valley; they’re often neurodivergent. I would say the same for high control religion, I just don’t think it’s discussed as much. I think it really impacts women or people socialized as female. They can really hide their neurodivergence by being all in on religion. That’s my story and that’s what I came to understand as I was writing this book. I recognized how God, ethics, and theology have been my special interests.

It feels so much better to have some way to make sense of that. So, what do you think – Peter Maurin – very, very rigid thinking, special interests, doesn’t seem to be able to predict that the Catholic church would respond as they ended up responding, which was not very generously to his ideas… Dorothy Day? Maybe?

I don’t know! I think in general, learning about how neurodivergence can look in hyper religious people, it’s hard for me not to see it in stories of the saints, or religious figures who were all in on religion…who took the tenets of faith so seriously and were really confused by how other people didn’t. So for me, white evangelicals were like ‘if you don’t believe this, you’re going to hell,’ so I was like well then I have to be a missionary! I was so shocked that not everybody wanted to be a missionary, if they said they believed this theology. And in a sense, I’m right! If you believe in eternal conscious torment for the vast majority of humanity and you’re not spending every single thought thinking about how to keep people from that kind of torment, I’m like ‘what’s wrong with you??’ But that’s me, and I’m autistic, and I recognize that.

But we do also see that a bit with the Catholic Worker folks who questioned why the Catholic Church wasn’t living out Catholic social teaching. And they just kept pointing it out over and over again in their paper. This is what the pope said, this is what scripture said, this is what these famous priests said. And they were always kind of shocked when it didn’t happen.

The other amazing thing about Dorothy is she was a single mother when she started the Catholic Worker movement, and had one daughter, Tamar. Later in life, Tamar identified herself as being on the autistic spectrum. As we know, autism is genetic. And in general, neurodivergent people are drawn to other neurodivergent people. So sometimes when reading about the Catholic Worker both in history and present day, I’m like yeah! These are a bunch of people with really deep special interests, maybe who struggle with black and white thinking, maybe have a bit of a hard time fitting into society as a whole. So I can’t make any claims, but there are some signs there!

Like you, I have emerged from a very high-control version of conservative evangelicalism and have had to sort through a lot of religious trauma (excess shame and guilt, fears about purpose in the world and making God angry, purity culture, etc). Part of my journey out of that religious space was discovering some radical Catholics, including Dorothy Day, and having it dawn on me that my religion truly didn't have all the good things in the world but that there was a lot of wisdom held by other people and traditions. Can you speak to how Day might serve as a healing guide out of religious trauma — and especially for autistic people who like having a sense of rule and structure for how they are "supposed" to do life, or "supposed" to do an exit out of a religion?

I love this question. It’s a complex question for a complex person. When you are autistic — and this seems to be especially true for women or people socialized as female — another person can be your special interest. And I didn’t know that. I thought your special interest was just like you’re really into trains, or whatever. I realized Dorothy was a special interest for me, and I wanted to be her. That’s not healthy. It’s not healthy to want to be anybody but yourself. It was helpful to process and come to terms with that inclination as I was writing the book.

If you come from any kind of religious background — but especially a high control religious environment like white evangelicalism — you are often taught that “we” are the only ones who have the right way forward. You believe that we are the only ones who have the right theology. We don’t study history. White evangelicalism has such a constricted intellectualism. I mean, I thought I was reading all the books I needed in college. I believed my professors who said they were giving me a full education of Christian history, and they weren’t! We only read people who came from one seminary. Being neurodivergent myself, I was kind of exploited – my naïveté was exploited by these institutions who said no, we are giving you all the information we need.

Today, I find it is so helpful and so grounding to be like, we’re just one little drop. And if we die, if that expression of Christianity dies, there are like a million more, and there have been throughout history. It’s not the end of the world; I don’t need to save it. It can die if it needs to! Being immersed in groups like the Catholic Worker and the leftist Catholics, it makes me feel better: there’s lots of different types of people doing this work.

And I can choose to deconstruct fully from religion if I want to, but if I want to choose to continue to engage in life through a framework of faith in some kind of higher power, Dorothy gives me such a good example. There are paths forward if you are obsessed with inequality, if you are thinking about housing all the time (which I do). There’s elements to various streams of Christianity where we can still be like that. So I love learning about alternate streams of Christianity. Black Christianity in America is amazing. Liberation theology and womanist theology are amazing. But I’m also very interested in learning from people who do not come from religion, and that’s a huge change for me. I used to only want to learn from people who were religious. I found it very grounding and very freeing for me personally, coming from a hyper religious background.

Anything else you’d like to add?

I no longer want to be Dorothy, but she is such an interesting companion if you want to read her writings, or read my book and get introduced to her. She’s a really complex, interesting individual and a person worth taking seriously, and that’s mostly what I wanted to do with this book.

You can find DL Mayfield’s book Unruly Saint at Bookshop.org or request it from your local library or independent bookstore. You can find her Substack here.

About the interviewer:

Christine Greenwald is a licensed mental health therapist in private practice in rural Ohio. She writes about religious trauma, ex-evangelicalism, and mental health on her Substack newsletter, Recasting Religious Trauma.

This was such an interesting read! I didn’t know anything about Dorothy Day or DL Mayfield, but now I want to know more. It makes me feel sort of - hopeful I guess? - to read such thoughtful, complex conversations around difficult subjects. Thank you for the great interview!

I yelped with glee when I saw the title of this post because I knew it had to be DL Mayfield. Loved this conversation and thank you both of you.