Wealth is the Missing Piece

If you want to talk about student loan cancellation, you have to talk about wealth

If you’re a regular reader of this newsletter, if you open it all the time, if you save it for an escape or forward it to friends and family and have conversations about it— consider becoming a paid subscribing member. You make work like this possible.

Consider three scenarios.

In the first, you grow up in the ‘60s and ‘70s. Your father, like most fathers in your generation, served in World War II. Because he was white, the GI Fund covered his schooling and provided assistance in buying in his first home, a modest three-bedroom, in the suburbs. You go to a decent or even good high school. Your parents buy new cars every few years, and even moved to a slightly larger home when you were in middle school, but nothing extravagant. They put aside a little money for college, which they’re able to do because they have no student debt and their mortgage payment is affordable.

When you apply for colleges, you opt for the most prestigious state school, where tuition, in 1974, is $3100 a year. Your parents agree to put $1500 towards that tuition, and by working all summer and a bit during the school year at $2 an hour you’re able to just barely cover your costs. It helps that your parents let you live at home during the summers. You worked hard, you finished your degree, and you have no debt. Your parents just bought a new car and give you the old one as a graduation present. When you get your first full-time job at 22, you start saving for a house immediately.

In the second, you grow up in the ‘80s and ‘90s. You go to a decent or even good high school, and grow up in a home that is anywhere from “modest” to McMansion, but that your parents own. At least one of them went to college themselves — and graduated without debt — which meant they were able to save a little for your college. You decide on an in-state school, and between that little that your parents saved for college, the amount you make from your summer job, a $500 scholarship from your mom’s chapter of the PEO, and a surprise graduation gift from a relative of $5000 to put directly towards tuition, you only end up taking out around $10,000 total to pay for everything associated with your undergraduate experience, including rent and books and pocket change, plus that extra semester you had to tack on at the end because you switched majors halfway through.

When you graduate, someone in your family advises you to consolidate your loans into one, so that you’ll just have one payment. The interest rate isn’t great, somewhere around 4.5%, but you’re able to pay the $104 a month, even though you were making around $35,000 a year at that first job. When you get laid off, instead of putting your loans into forbearance, your parents float you the payment for three months until you can find a new job.

After ten years, you pay off your loans in full. Because your payment was low, you were able to direct more towards your 401k, and even start to build up an emergency fund. You worked hard, and your debt is gone, and now you can direct that $104 a month straight into the account where you’ve been saving for a down payment on a house.

In the third scenario, you grew up in the ‘90s and ‘00s. Your parents managed to put a small down payment on a home in the ‘90s, but it got foreclosed on during the Great Recession. For most of your teens, your family moved between rentals, and none of your teachers know you well enough to write a great recommendation letter, but you still manage good grades.

When you get the acceptance letters to various colleges, everyone is overjoyed that you’re getting money from every school. Because your family makes $50,000, you get Pell Grants, plus each school is offering you some scholarship. You think, because everyone and everything has told you as much, that the best way to set yourself on a path to success is to go to the very best college you got into — even though it’s in a place where it costs more to live, and that requires a long bus or train or plane ride to get there. You work summers and have a work-study job in the library and babysit for professors but still have to take out loans to cover books, and coming home at Christmas when the dorms close, and covering rent and food in the expensive cost-of-living city for a summer when you get an internship that promises to be a stepping stone into your industry.

You graduate with $50,000 in debt, including a $5000 private loan with high interest you had to take out for emergency dental work. No one tells you about consolidation so the first few years after you graduate you’re paying a bunch of different servicers as much as you can, and sometimes one or another falls by the wayside, and then you get laid off, and still try and pay some of the monthly amounts, and put your cell phone and utilities and groceries on a credit card whose balance just keeps going up.

You get a new job and decide you’re going to get your life in order. You realize that over five years of paying as much as you can, your balance has somehow gone up, even on that private loan that you keep trying to pay down. Your $50,000 has grown to $60,000, plus you have around $10,000 in credit card debt. At this point, your credit is crap. There’s no regular public transportation between your job and the area of the city where it’s cheap enough for you to live, so you have to buy a car, but your credit doubles your interest rate.

Your parents are managing to cover their own bills but don’t have anything left over. No one in your extended family has money to give; in fact, you’re trying to send your sister, who’s now in college, a hundred bucks every month so she doesn’t have to resort to credit cards like you did.

You get on an Income-Driven Repayment Plan, which means that you only have to pay 10% of your discretionary income every month towards the (public) loans. You keep chipping away at the private loan but it feels like you’re just paying the interest. Same for your credit card bill. You have no emergency fund. Forget about saving for a down payment. When your cat gets sick and has to go to the vet, you put the $500 charge on your credit card because what else are you supposed to do. You’re making $80,000 a year which is more than your parents ever have and you feel like you should feel rich but somehow you’re still very much in the hole.

After ten years, your public loan balance isn’t that much lower than when you started. You worked hard, and then you hear that $20,000 of your Pell Grants will be canceled, and that because of the other reforms to Income-Driven Repayment plans, your loans will no longer be collecting interest, and you’ll only have to allocate 5% of your discretionary income towards payment. If you keep making those payments, in ten years, the remaining balance will be canceled as well. You’ll be somewhere around 41 years old. Maybe then you can start thinking about a down payment. As for your retirement plan, it’s the same as your parents’: work until you die.

●

We’re accustomed to talking about these sorts of stories as stories of privilege. But a better way of thinking of them, particularly in the context of student loan forgiveness, is as stories of wealth.

Wealth is the floatation device that spreads vertically and horizontally through your family, buoying all those close enough to gain access. The size of that floatation device — and how many people it can keep afloat — depends on how many people are bolstering it (through their own security) and how many people need its support.

Wealth is having an emergency fund to help others in your family, and enough others in your family also having an emergency fund that the need will always be distributed. Wealth is inheritance, of course, but wealth is also planning for retirement in a way that assures costs will not be shouldered by other family members. Wealth can take the form of a union pension, or assistance with a down so the borrowers don’t have to take out mortgage insurance. And wealth is not having to take out student loans — or, if you do, only having to take out a very small amount of them.

In the vast majority of cases, class security is not the result of individual income, but familial wealth. And while we understand this concept when it comes to, like Scrooge McDuck and the privilege of his cartoon nephews Huey, Dewey, and Louie…..or Logan Roy and his four feckless and/or reckless children, it’s much harder to conceive of when it comes to those who aren’t spectacularly, lavishly, publicly rich.

Take the families in the first two scenarios above. Both would likely think of themselves as middle-class, and their yearly income level might align with that understanding. But they have wealth: in their homes, in their credit score, in their savings, in their ability to cushion their child’s intermittent economic needs.

But again: most Americans don’t think of wealth this way. Instead of considering the overall breadth and depth of their family’s life preserver, they look to what they feel they are able to save every year. Not what they make, but what they understand as extra.

Which helps explain why a full third of Americans earning more than $250,000 a year say they’re living paycheck to paycheck: there are a lot of costs involved in being upper class. People spend a ton on mortgages, and private school tuition, and memberships, and 401k allotments, and 529 college savings plans. They would never understand themselves as poor, but they also don’t understand themselves as rich, either.

The key point about all those costs, though, is that wealthy people can pay them — only one in ten of those making $250,000 report problems in covering their bills. Even more importantly, they still own their homes. If they had to sell it, they could (And if they’re making over $250k, that house is almost certainly in a place where its value has appreciated). But that doesn’t figure into their daily understanding of abundance, and, as such, their understanding of themselves as wealthy.

There are some notable caveats here. Let’s say they’re the only person in their family making $250,000 a year. Let’s say they’re helping their cousin pay college tuition. Let’s say they’re paying a minimum of 10% of their discretionary income on student loans, which they had to take out for the undergraduate and graduate degrees that allowed them to get to a place where they are making $250,000.

Let’s also say they have kids, and the only way they keep making that $250,000 a year is to pay something for childcare — or have a partner who significantly cuts or eliminates their income to provide that labor themselves. Let’s say no one in their family could afford dental care growing up, and now they want to help make sure their nieces and nephews have braces. Or let’s say they’re Black, and their home value decreases simply because they’re Black, or their home insurance costs have become untenable because of climate change.

That person has a large income, but they have significantly less wealth. Their floatation device is in danger of sinking, and if it does, there’s no one to pump it back up.

Sociologist Louise Seamster was the first person who described wealth like this to me, and she does it again in this conversation with Tressie McMillan Cottom, where Cottom responds:

Listen, I’m one of these people. I send money out to cousins, aunts. I don’t have any children, but I pay childcare costs. I’m paying for my niece to get her music lessons and/or horseback riding lessons. Yeah, don’t cry for me, Argentina, but I send money up and down the chain. I subsidize my parent’s healthcare costs as they get older.

So what I look like on paper income wise is very different when you start talking about wealth and where we draw sort of the meaning of those income differences. I want to talk about that a little bit. Because one of the reasons why it’s so difficult, I think, to talk to that median white household family member, student loan debt holder is because everything you just talked about, about wealth doesn’t feel like wealth to the people who are experiencing it, right?

These ideas build on Melvin Olivier and Thomas Shapiro’s seminal research on the differences between Black wealth and white wealth, first published in 1995. As Seamster summarizes:

….[Oliver and Shapiro] revealed that researchers focusing on seemingly converging income differences were missing much larger wealth disparities. Not only did Black families’ wealth amount to only one-tenth of White wealth, but their wealth was qualitatively different. For instance, Black families lacked the intergenerational inheritances that subsidize things like education and down payments on homes and provide Whites with a cascade of life-long advantages. The scope of the disparity is hard to fathom: the 100 wealthiest families on the Forbes list own as much wealth as all Black Americans combined.

This line of thinking helps us understand how policy decisions — like the passage of the GI Bill, which guaranteed college tuition, low-interest home loans, and unemployment insurance — can have ongoing buoying effects on generations of Americans — and what happens to the families of the 1.2 million Black GIs who were largely excluded from those buoying effects.

Same goes for the effects of the The Homestead Act, which, in addition to stealing Native land and gifting it to 1.6 million homesteaders, was almost entirely limited to white Americans and immigrants. (Only 4000-5500 Black Americans ultimately received land).

Same goes for who was included and excluded (namely: farm and domestic workers) from the National Labor Relations Act in order to sate Southern Democrats who refused to allow their (predominantly Black) workers to unionize and obtain access to the sort of stability and pay that build wealth, and the Social Security Act, which also excluded farm and domestic workers from the unemployment and “old age” benefits that have now become standard. (65% of Black Americans fell outside of the reach of the original act when it was passed in 1935 and remained excluded until 1954).

Same goes for the FHA’s redlining practices that excluded Black Americans from access to mortgages, and same goes for the property taken from Japanese-Americans during Internment, and, again, the ongoing violation of hundreds of treaties with Native tribes.

The government has repeatedly and unapologetically made it easier for White people to obtain wealth — and refused to acknowledge how those same policies made it far more difficult for anyone who wasn’t white to obtain or sustain wealth. And because white people have largely been responsible for the way these programs have been narrativized, their function as explicit and exclusionary wealth builders has largely been erased. Instead of reading the enduring racial wealth gap as the result of decades of racialized policy, the blame is shifted to the individual, or expanded to an entire race: “those people” just don’t want to work.

To accumulate wealth as a person of color in the United States is like hitting a single, working doggedly to steal every base against the odds, nearly getting called out every pitch, and then watching a white person magically appear on Third, saunter to Home, and chide you for taking so long to score a run.

●

Self-sufficiency structures the core of the American mythos: a person’s success is the result of one person’s hard work, and that person’s desire to work hard is a sign of good character, and any resultant wealth is God’s will. But wealth cannot be sustained by one person, even with the assistance of God. It doesn’t matter how hard you, as an individual, work, if you don’t have the larger floatation device for when catastrophe strikes. Because it happens to everyone: the economy tanks, someone gets diagnosed with an illness, a kid needs a lot of special care that’s not covered by insurance, a home burns, a car crashes, whatever, shit happens (maybe not to even to you but to somebody you care about or for)! The character of the shit matters far less than wealth’s ability to keep the individual from drowning in it.

In 2007, the shit hit nearly everyone. At that point, the racial wealth gap between White and Black Americans was 10.0 — as in, for every dollar of wealth held by the median Black American, the median White American held ten. By 2013, that proportion had risen to 12.9. During the same period, the White-to-Hispanic racial wealth gap rose from 8.2 to 10.3. If you just look at the space between 2005 and 2009, the median net worth of black households fell by an astonishing 53 percent, and Hispanic household wealth fell 66 percent. At the same time, white household net worth went down just 17 percent.

So what was going on here? Part of those losses can be explained by the fact that sub-prime mortgage lenders targeted (and then foreclosed) on homeowners in Black and, to a lesser extent, Hispanic neighborhoods. But a whole lot of that net loss in wealth can be attributed to taking on new student loans.

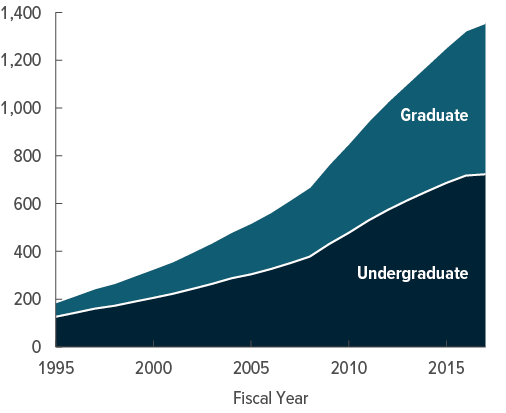

Think back to October 2009, when we were still deep in a global recession. 23.8 percent of Black workers, 25.1 percent of Hispanic workers, and 14.2 percent of white workers were either unemployed, under-employed, or had stopped looking for work. Now try and remember the messaging towards people struggling during that time. Go back to school. Finish that degree. Re-skill yourself. Or go to school for the first time, and get a degree that’s guaranteed to get you a job. Or if you’re in school already, why not keep going? Just look at this graph:

That Great Recession jump! And that’s just public debt!

Some (wealthy) students’ college funds had been decimated by the market crash, which meant an unexpected need for loan dollars. But many prospective students were, essentially, marks.

Tressie McMillan Cottom wrote the book on what was going on at for-profit colleges during this time — how they targeted people who were desperate for a route out of unemployment (and towards the dream of wealth!), pumped them to max out their public loans (and add on private, with much higher interest rates), and then provided little to no assistance to complete their degree. (Between 2006 and 2010, enrollment in for-profit colleges went up a whopping 76%).

We know now what exploitative institutions like Corinthian College were doing. But at the time, most people understood these institutions with snazzy websites and serious-sounding names as colleges like any other. And college still felt like a clear path out: out of your crappy job that didn’t even cover the bills, out of unemployment, out of precarity. It was a way to invest in your future. It might not bring back the house your family lost, it might not be an emergency fund, but it was the closest you could get towards a glimmer of that promised, elusive wealth.

But the debt students took on to pursue that dream was not distributed equally.

Today, 21% of Black Americans have student loan debt — compared to 14% of White Americans. And they take on significantly more of it: in 2021, one year out from graduation, Black women owed an average of $41,466 for undergraduate and $75,086 for graduate school — compared to $33,851 for undergraduate and $56,098 for white women.

It’s a prime example of what Seamster and co-author Raphaël Charron-Chénier call “predatory inclusion”: a process in which institutions target those most desperate to participate in wealth building (through a college education or home ownership, say) but then leverage that desperation for profit — which generally means sustained debt, not wealth, for the borrower. It’s like opening the door to the American Dream, promising equal access to all, but putting a trap door underneath people who aren’t white — and then throwing them a rotting ladder.

●

In this way, student loans have become a way for Black Americans to access the foundations of wealth — decades after the GI Bill allowed white Americans to access the foundations of wealth. But college costs much more now (in part because politicians and voters chose to dramatically reduce public funding, starting in the 1970s, hrmmm I wonder what else was happening at that time, couldn’t be desegregation of public institutions) and many fields now require a graduate degree to gain steady employment. As a result, students take on levels of debt that can quickly move from “good” (debt that helps maintain good credit, has a guaranteed future payoff, and allows you to accumulate equity) to “bad” (debt that causes you to go even further into debt).

As Seamster and Charron-Chénier explain, “[c]onceptualizing debt as the negative image of assets—as something to be subtracted from assets to determine net worth—can distort our picture of inequality because debt is not always a burden. It can also provide significant advantages—if it is the right kind of debt, deployed by the right person.”

And because of the racial wealth gap, a white person is much, much more likely to be “the right person.”

For example: the default rate for Black borrowers who entered repayment by 2017 is 32 percent across all institutions — compared to 20 percent of Hispanic or Latino borrowers, and 13 percent of white borrowers. (The default rate for Black borrowers whose loans originated from private, for-profit schools = 42 percent).

Those numbers aren’t because Black borrowers are somehow irresponsible with money. It’s a symptom of the absence or decline of family wealth. Lack of family wealth made loans necessary; lack of family wealth made it difficult to cover payments. A loan in default doesn’t just tank your credit score. It prevents you from getting hired by the government in any capacity. You’re excluded from all government contracts, including via the military. In some states, you can lose professional certification. In this way, the absence of wealth can easily transform student debt into bad debt.

This is what I don’t think people complaining about student debt cancellation do not understand, particularly when it comes to the $20,000 Pell Grant cancellation: it is targeted at people without family wealth, people whose debt has a high likelihood of turning into bad debt.

Today, 66% of Pell Grant recipients come from families with incomes of less than $30,000. Again: less than $30,000. Another 28% come from families that make between $30,000 and $60,000 a year. Given what we know about the racial wealth gap, it makes sense that Black borrowers are twice as likely as white borrowers to have received Pell Grants (other borrowers of color are also more likely than white borrowers to have received Pell Grants). Early projections suggest that around one-third of those receiving relief are Pell Grant recipients — and 3.8 million of Black borrowers will have their debt canceled entirely.

Now, there’s a strong argument for targeted student loan cancellation for all Black borrowers as the closest we might come to modern-day reparations: a way of monetarily righting the wrongs of not just chattel slavery, but the continued barriers to wealth accumulation that have come since. And I believe this, and I support it fully — while also understanding that no contemporary president is likely to successfully pull off this sort of race-based policy, at least not with the current Supreme Court.

Which is why I also believe the current targeting of Pell Grant recipients, combined with the significant changes to the way loans are handled and accrue interest while in repayment, and the continued prosecution and regulation of for-profit colleges, makes it far less likely for this student debt to turn into bad debt — and, in some cases, it might allow borrowers to move into wealth building essentially overnight.

And yes, this will be true for some borrowers who aren’t Black as well — including millions whose debt is “good.” But canceling or modifying terms on bad debt is worth way more than the simple monetary value. Canceling $20k in bad debt for someone without wealth — while also getting rid of interest and promising total forgiveness after ten years of payments — isn’t just lowering a balance. It’s altering the trajectory of their entire lives, and their future family’s lives, in a way that people with wealth could only understand if they went back to the first person in their family tree with access to wealth-building in some form, and thought about how dramatically different their lives would be without it.

As of 2000, there were 46 million adult Americans whose Grandparents, and Great-Grandparents and Great-Great-Grandparents had received free land through the Homestead Act — a quarter of the US adult population. It’s worth thinking about, particularly if anyone in your life has “put themselves through college” or if your family has a narrative about its own work ethic. What mechanisms made that sort of wealth, even if your family never dared call it by its name, possible?

●

Cancellation is the beginning, but affordable college is the future: high quality education that puts no one into significant debt is the only way we move forward as a society committed to any form of equity. Does that require investment in public institutions? Absolutely. Do I believe my tax dollars should go towards ensuring others’ debt-free future, even if I myself will not directly benefit from it? Without a doubt, just like I’m on board with paying for elementary school, and roads I don’t travel, and library hours I don’t use, because I believe that paying for civilization rules, and willingness to fund programs that make it possible for people to live lives without suffering or precarity is a sign of a healthy and empathetic civilization.

When I finished graduate school, I had accumulated $118,000 in debt, and spent many years bitter and anxious about it. But I was never, ever in danger of default. I knew my parents would help me in case of catastrophe, or that I would go into forbearance and resume payment later. I knew that I was free from undergraduate debt, because my parents had saved, but also because my Granddad, a GI who got an MBA and bought a home, got a job at 3M, accrued a lot of stock, and some of that stock was in my Grandmother’s name, and when she died, she gave it to me to pay for around a third of my college. He worked hard, and my parents worked hard. But they did not work any more or less hard, not in the grand scheme, than anyone else who hoped for their children’s future.

Today, I have been able to take a part of each book advance and dedicate it to my loan balance, and when the pause ends in December, I will, twelve years after finishing my PhD, pay off that balance in full — including the many tens of thousands in interest it accrued since I took out my first graduate loan in 2005.

I have been able to do all of that in large part because my family had and has wealth and my partner’s family had and has wealth: not the sort you’d ever gawk at, or talk about, or brag about, just the sort that makes a family disappear into normalcy, into still feeling like they don’t have as much as others, into what can very quickly feel like lack, and resentment when others receive something that you do not — in part because all you are thinking about are the gifts and privileges of the very present moment, not the long-term presents of the past.

Debt “forgiveness” has always struck me as the wrong phrase, because it conceives of the debt itself as a sin — when in fact, it is the opposite. The sins of the past are what have placed us in a position of wealth inequality: the sort whose spiraling effects can be traced to rising rates of maternity mortality, incarceration, infant mortality, and so much more.

Wealth does not create happiness. But in its practical form, the way we’ve been talking about it here — it facilitates it. It is a promise we hope to give to those we love most. The government does not love anyone. It does not care. But it has, historically, allowed different types of people to give that gift of wealth more freely. These initial cancellations do not tip the scales — not even close. But they begin the process of evening them. ●

Further Reading:

Student Loan Debate Reveals Limits of Economist-Style Thinking

The Case for Reparations (no seriously)

Lower Ed: The Troubling Rise of For-Profit Colleges in the New Economy

What the student loan payment pause has meant to Black women

How the GI Bill's Promise Was Denied to a Million Black WWII Veterans

Are you ready to join the community? Do you want access to the weekly links and “Just Trust Me?” Do you to be able to comment and be part of the Discord? Well, then:

Subscribing is how you’ll access the heart of Culture Study. There’s those weirdly fun/interesting/generative weekly discussion threads, plus the Culture Study Discord, where there’s dedicated space for the discussion of this piece, plus equally excellent threads for Job-Hunting, Reproductive-Justice-Organizing, Moving is the Worst, No Kids Club, Chaos Parenting, Real and Potential Austen-ites, Gardening and Houseplants, Navigating Friendships, Solo Living, Fat Space, Lifting Heavy Things, and so many others dedicated to specific interests, fixations, obsessions, and identities.

If you’ve never been part of a Discord: I promise it’s much easier and less intimidating than you imagine.

As always, if you are a contingent worker or un- or under-employed, just email and I’ll give you a free subscription, no questions asked. If you’d like to underwrite one of those subscriptions, you can donate one here.

If you’re reading this in your inbox, you can find a shareable version online here. You can follow me on Twitter here, and Instagram here — and you can always reach me at annehelenpetersen@gmail.com.

Thank you for this deep dive. I appreciate these white middle class scenarios and would love to see them done for working class white folks as well as people of color.

I know a lot of my white family members don't understand the amount of wealth that still comes with being working class white compared to other races. My maternal grandfather was rejected when he tried to enlist in WWII due to high blood pressure. Neither of my parents have college degrees and they suffered financially for it because the goalposts shifted - as young adults in the 1970s, living wage jobs existed straight out of high school; by middle-age in the 2000s those same jobs required 4 year degrees and higher positions at the same employer required higher degrees, so suddenly "working your way up" no longer became an option.

I was able to get to where I am today because of what I call "The Loser's Lottery": fortuitous things that we benefited from at the sacrifice of others. My paternal grandfather got lung cancer from asbestos from working at a steel mill and won a settlement. My maternal grandparents owned farmland that became valuable to the County Government because it was on the waterfront and adjacent to a county park. After a long fight, they were paid fairly for it. My father worked as a correctional officer and almost died the first time at age 43 and then did die at age 52; some of the life insurance policy that my mother had for him covered my undergrad student loans.

What if those pay days never happened? Particularly with my paternal grandfather and dad - they worked dangerous jobs in order to earn a middle class income, and then said jobs turned into winning the loser's lottery at the expense of their health and lives. What if my maternal grandparents' farm was somewhere undesirable, even for developers? What if they didn't have my cousin lawyer (whose path to law school and practice was through the military?) to help them get a fair price for their land?

The reality is that we would still be working class, and I'd still be in a boatload of debt from student loans, and would feel really relieved by the loan forgiveness because it would feel like I finally won the lottery for once in a good way. Also, we'd still have more wealth than families of color because even though we suffered we still are worlds ahead in wealth.

What's hard for me is that I'm not allowed to publicly talk about "The Loser's Lottery" per my extended family, so I look much more self-made than I am.

I grew up ok; child of immigrants but my parents were able to work their way up in their careers sans educations and it set me and my older sister up well. My sister and I were first to go to college, but good school and with enough "know how" to figure out consolidation, etc. I had about $50K in debt that I'm still paying off and will get $20K in relief from. When I met my partner I knew they were well off but didn't realize all the ways wealth works. A few things I've noticed:

*First, the amount of strategy that goes into avoiding paying taxes. I thought everyone just paid what was due at the end of the year but for my partner's family they do things like give my partner a check every year for the maximum gift amount to avoid estate taxes when they die. Same thing for my partner's parents which means my partner gets a full salary in gifts just to start. Recently my partner's parents moved real estate holdings into an LLC that's owned by my partner and their siblings but that the parents still use for themselves for all intents and purposes; doing so was a way of off-setting taxes they would have had to pay from the success of their business. This off-set was in the mid-six figures.

*Second, my partner consistently thinks of budgeting and money in terms of their net worth. As someone with debt who had a negative net worth up until two years ago (and is only on the positive side because of 401K I can't access) I worry about money and budget in terms of what my salary covers and what I spend. My partner knows that even if salary doesn't cover spending, they don't have to worry. This blows my mind.

*Third, my partner and their family aren't bad people but consistently believe that their wealth is due to their hard work and being frugal. For example, they do a lot of things around the house on a DIY basis like not paying for a landscaper and doing it themselves. For my family, the goal was to have enough money to not need to spend time on things we could pay other people to do. I think the fact that we always *had* to do the DIY work meant that not having to do it was the goal. My dad still fixes his own car, he refuses to pay repairmen for appliance problems because he would rather figure it out on his own *and* because he can't afford to. My partner's dad recently totaled his expensive car trying to fix it himself.

*Finally, my partner consistently says that they grew up middle class. I don't think this is an instance of making $250K to live paycheck to paycheck like the article suggests but rather the mindset that allows a very wealthy family to think of themselves as just hard working americans whose hard work has paid off. In this way, my partner is very uncomfortable with student debt relief because it feels like someone isn't working hard enough.

Please don't share all of this outside of culture study, it's something my partner and I are working through and is very hard in ways that are surprising and have made me feel so completely illiterate when it comes to really understanding wealth. It seemed helpful to share.