What Happened to People Magazine?

How the Most Important Celebrity Magazine of the Last 50 Years Started Endorsing "The Best Air Purifiers of 2024"

Real talk: I made the decision to keep this long, reported essay outside of the paywall, because I want to keep as much Culture Study freely accessible as possible. But this post is the result of many hours of labor — and without your subscriptions, there’s no free Culture Study. If you believe in this project, consider subscribing:

Subscribing gets you access to the weekly Things I Read and Loved at the end of the Sunday newsletter, the massive links/recs posts, full Garden Study access, and all the weekly threads, like yesterday’s extremely useful thread on Clothes Maintenance and Repair (how do you repair kids’ blasted-out knees in pants? what do you do about moth holes in sweaters? how do you keep linen in good shape without becoming a full-time iron machine? how do I get the blood out of my hoodie sleeve?) and Friday’s expansive discussion of kids’ allowance.

I’ve been obsessed with People Magazine since I first understood what a magazine even was. My family didn’t have a subscription but I would stare at the cover every time we went to the grocery store and paw at the old, worn copies in the doctor’s office. Highlights was kid stuff; National Geographic and Time were boring; I knew about Tiger Beat but never knew anyone who had an actual copy; Weekly World News, with its black and white newsprint and incessant bad boy stories, was terrifying.

But People! People was filled with the average yet extraordinary. There were pictures of Princess Diana, of course, but also pictures of someone who’d given birth to triplets on an airplane, and an elderly lady who made cakes shaped like every fruit in the world. It was like my favorite book of fourth grade (The Guinness Book of World Records, 1990) but with better pictures and much longer stories (and, once a year, the Sexiest Man Alive, which was somehow always Richard Gere).

When I got to grad school and eventually started my dissertation on the history of celebrity gossip, my favorite chapter was about the founding and accumulated power of People. As a Time Inc. publication, it mixed the established journalistic rigor of Time (everything went through fact-checking! they hired real journalists!) and “extraordinary stories about ordinary people” whose subjects could range from Gerald Ford (who appeared in a pool for the cover of the fourth issue) to “a zookeeper who lost a finger to his favorite anaconda.”

By 1977, People had reached three million in guaranteed circulation — an absolutely wild number just three years after launch. People held that number for more than two decades, with massive (and massively profitable) direct sales at the newsstand. In the late ‘90s, guaranteed circulation hit 3.5 million; in the second half of 2002, sixteen consecutive issues of the magazine hit 1.5 million in newsstand sales alone, and total circulation reached 3.6 million.

If you’re looking for in-depth citations of these figures and the anxiety People and its knockoffs produced, you can find them in my dissertation. But the reason I’m still interested in People Magazine is the same reason I was interested in it as a kid and as an academic: it was stories about people. More plainly, as Stolley put it back in 1974, “we’re getting back to the people who are causing the news and who are caught up in it, or deserve to be. Our focus is on people, not issues.”

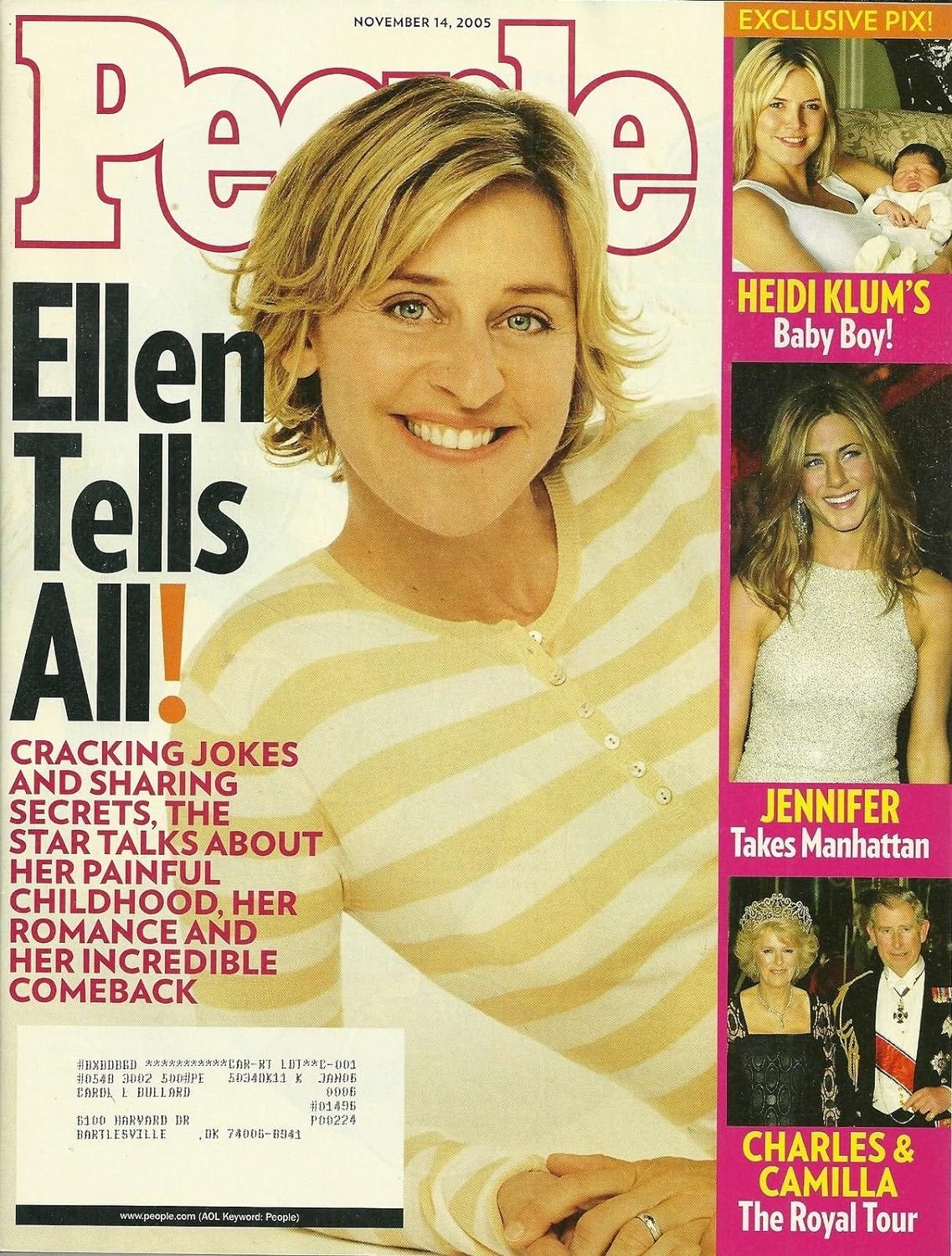

NOT ISSUES. Not political realities. Just people’s personal stories. And with that framing, you can put a president on the cover and claim it’s “not political.” You can put Ellen on the cover and not say gay.

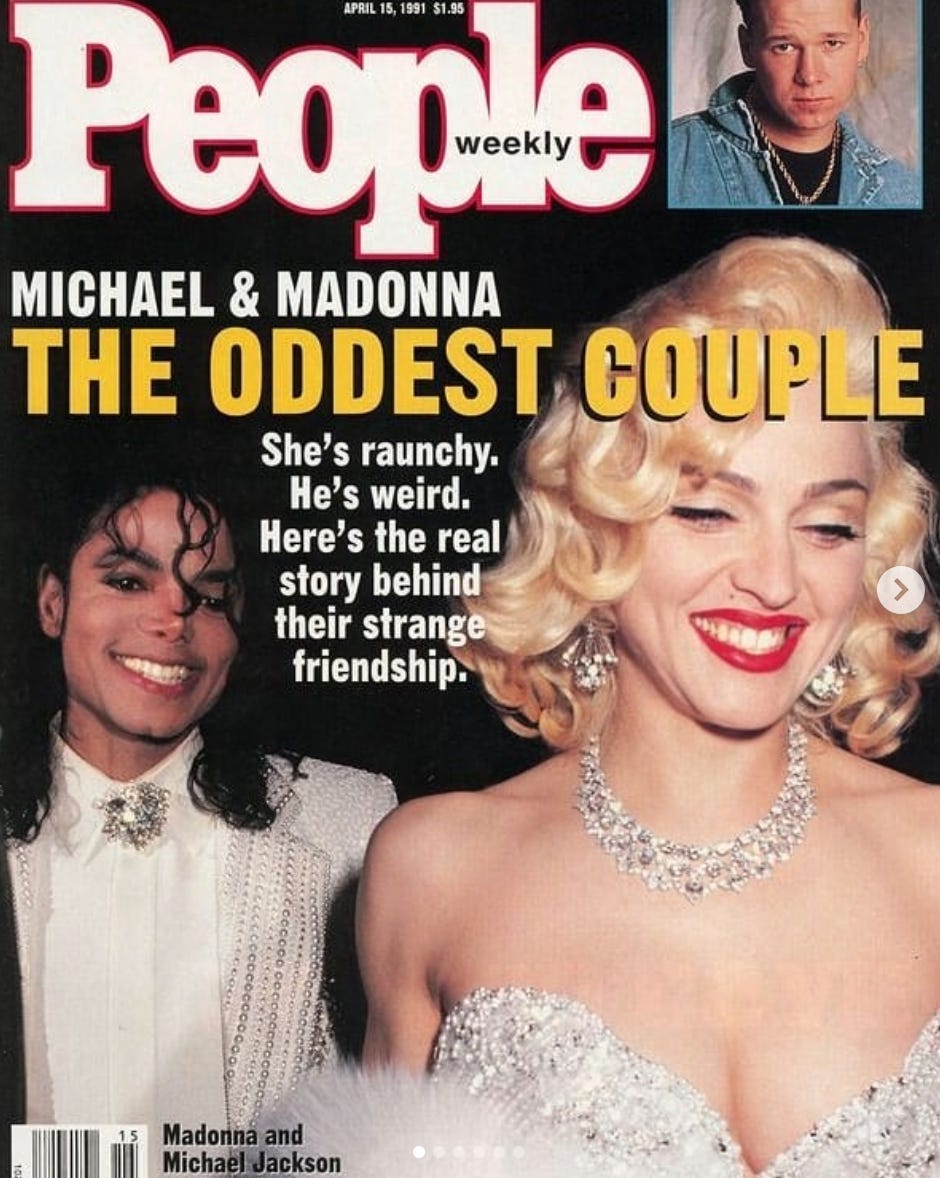

Or you can put Lance Bass on the cover and say gay, but not talk about the politics of homophobia that contributed to being “hurt by rumors.” You can feature royalty without talking about the wages of empire, and you can talk about Michael Jackson and Madonna like……this:

The excavation of the political from the personal is always worth studying, which is part of the reason People has always been such a rich text. But today’s People Magazine is thinner, less glossy, and generally less substantive than its heyday. There are so many reasons for the magazine’s declining influence, most of them related to its own stubbornness when it came to online content in the early 2000s, the ill-fated Time Inc. merger with AOL, the rise of the “new” unsanctioned scandal press in the form of upstart gossip blogs, the spread of celebrity social media, and the ongoing contraction of print media and print advertising.

And yet: the People brand is still incredibly lucrative. To understand why, we have to do a little industrial history. In 2017, the Meredith Corporation purchased the suite of Time Inc. publications, including People, Entertainment Weekly, InStyle, Real Simple and Travel & Leisure. In 2021, Meredith was acquired by the media conglomerate IAC Dotdash, which rolled all of the online and print publications together under a subdivision called Dotdash Meredith.

If you’ve never heard of Dotdash, you’re not alone. But you’ve almost certainly found yourself on a Dotdash site after typing a question into Google. There’s The Spruce (food and gardening and households), VeryWell (health), TripSavvy (travel), Lifewire (tech), The Balance (personal finance), ThoughtCo (education)….and so many other ambiguous but professional-sounding titles.

The first time I found myself on one of these sites, I spent a solid five minutes trying to figure out if it was a legitimate source or a weird SEO farm. I worked in media! How had I never heard of this thing! Here’s the truth: these are real sites, with real articles written by real people. And they are also absolutely SEO farms.

The Spruce, along with the rest of those millennially-named and branded sites, is the current manifestation of what was originally and aptly called The Mining Company. The Mining Company was founded in 1997 to provide reliable online information in hundreds of different subject areas; in 1999, it changed its name to one you’re more likely to recognize: About.com. 1990s era About.com was a mix of AskJeeves, Wikipedia, and Encarta, and years before what we understand as anything close to “search engine optimization,” people understood its value: the publishing conglomerate Primedia paid $690 for it in 2000 at the peak of the dot-com bubble before selling it off to the New York Times Media Company in 2005 for $490 million.

Under the New York Times, About.com used ads on its various “articles” to increase its revenue to over $100 million. But the financial crisis (and the ever-changing norms of the internet) tanked revenues, and by 2012, the Times Media Company offloaded About.com to IAC. (It was nearly sold to Answers.com, a tidbit I include simply to delight you).

When I mentioned IAC above, I called it a conglomerate, and that’s right. But it’s also Barry Diller’s conglomerate, and Barry Diller is a certain sort of conglomerate mastermind. He was one of the first movie executives to understand the potential to exploit video game I.P.; he launched the Fox Network; he repopularized the WWE during his tenure at USA; he saw the early value of Expedia and online dating sites like Match.com and Tinder.

Diller understood that internet properties’ value centers weren’t their content. It was their capacity to transmit ads. So when IAC acquired About.com, it put Neil Vogel in charge as CEO, and fiddled around with making it less ugly and more accessible on mobile. Still, year after year, it kept losing money. So in 2017, Vogel made a radical change. About.com and its one million articles would cease to exist. In its place: The Spruce and its millennial-branded siblings, now named DotDash, which would house reformatted and updated About.com content and branch out into shopping guides packed with referral links and Wirecutter-like reviews.

Dotdash took the heart of a “service” publication (advice, buying guides, how-tos) and made it into evergreen exploitable content. It significantly increased the amount of text in each article (which made it seem more substantive in Google’s ratings) and decreased the number of images and videos (which helped make the site load faster). Vogel’s corporate mantra: “the freshest content on the fastest sites with the fewest ads.” By 2020, Dotdash was home to more than 250,000 “super articles” on a dozen individual sites that reached 90 million Americans every month.

It doesn’t matter if the brands themselves were bland and forgettable, or if you glanced at the author name beside an article and never thought of it again. The package itself — the font, the absence of intrusive auto-play ads, the review board descriptions — underlined the sites’ legitimacy.

At this point, Dotdash had already acquired Byrdie (a beauty site), Brides.com (from Condé Nast), Liquor.com, Treehugger, Serious Eats, and Simply Recipes. Vogel called the strategy “a Netflix approach to content creation,” which explains the 2021 decision to shell out $2.7 billion for Meredith and the more than 30 magazines and brands under its umbrella. That’s Shape, Southern Living, Allrecipes.com, Parents, Health, Food & Wine, Diabetic Living, Better Homes and Gardens, Health, Every Day with Rachael Ray, plus all of those Time Inc. titles Meredith acquired back in 2017. Including: People Magazine.

●

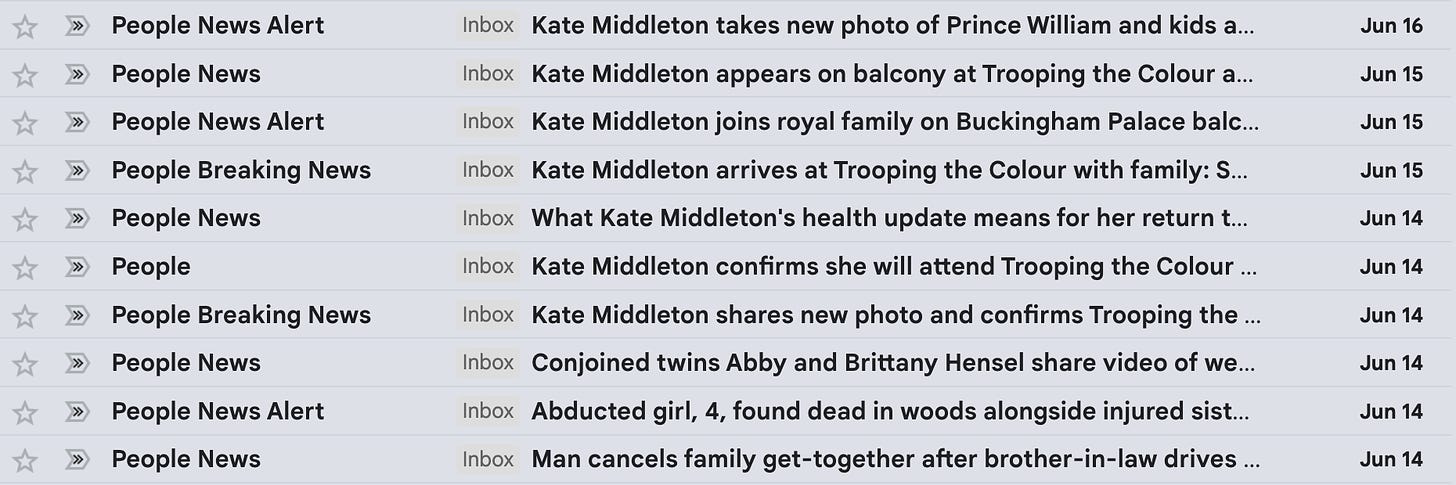

I’ve been on the People email list since 2010. Every year, I get more and more emails; the content is always fascinating, in that bewildering what is culture sort of way. I wake up and wonder: what does People care about today? Well, this past weekend, the answer was almost entirely Kate Middleton.

A few weeks ago, it was the deeply sad story of Levi Wright, the three-year-old son of a rodeo star who rode his toy tractor into a river. But there’s also a tremendous amount of Jennifer Lopez/Ben Affleck/Jennifer Garner coverage, an average number of Kardashian posts, and solid numbers of Taylor Swift outfit and relationship updates. Occasionally, there will be an “exclusive” interview with a star who “tells all” (most recently: Hugh Jackman and Ryan Reynolds interview each other) but the vast majority of content can be sorted into five buckets:

A celebrity posts something on social media, and a People article then links to the social media post and repeats what they said (from Monday: “Richard Gere Poses with His Sons in Rare Photos Shared by Wife Alejandra: 'Always There for Us’”)

A celebrity does an interview with a higher profile magazine or television show and People aggregates one or two quotes from that interview (“Anne Hathaway Reveals She Had a Miscarriage in 2015, Recalls 'Pain' of Trying for Baby’)

Something very weird or very random or very horrible happens to a non-celebrity, and People picks it up (“Woman Eats Only Two Foods for Five Years Due to Severe Allergies (Exclusive)” plus a lot of other influencer and true crime related gruesome stuff I won’t link to)

Something “goes viral” in some way on a social media platform and it’s spectacularly easy to make a post about it without doing even a minute’s worth of additional reporting (“Dad Skips Son's High School Graduation for Another Family Event: 'I Will Always Come Second';“Pregnant Mom's Viral Search for Baby Name in Cemetery Is Complete! Find Out the Unique Name She Chose Off a Grave”

A celebrity photo used as a peg for a shopping post filled with affiliate links (Reese Witherspoon Keeps Wearing Shirts and Dresses with This Pretty Detail — Shop the Trend from $16)

This sort of aggregation and low-lift content creation is not novel — it was the backbone of BuzzFeed for years and now serves as its entire skeleton; it shows up in slightly different form in local stories that get picked up by the Associated Press and reprinted in papers all over the country. Print and television tabloids have exploited human interest/it could happen to you/true crime components of People content for decades.

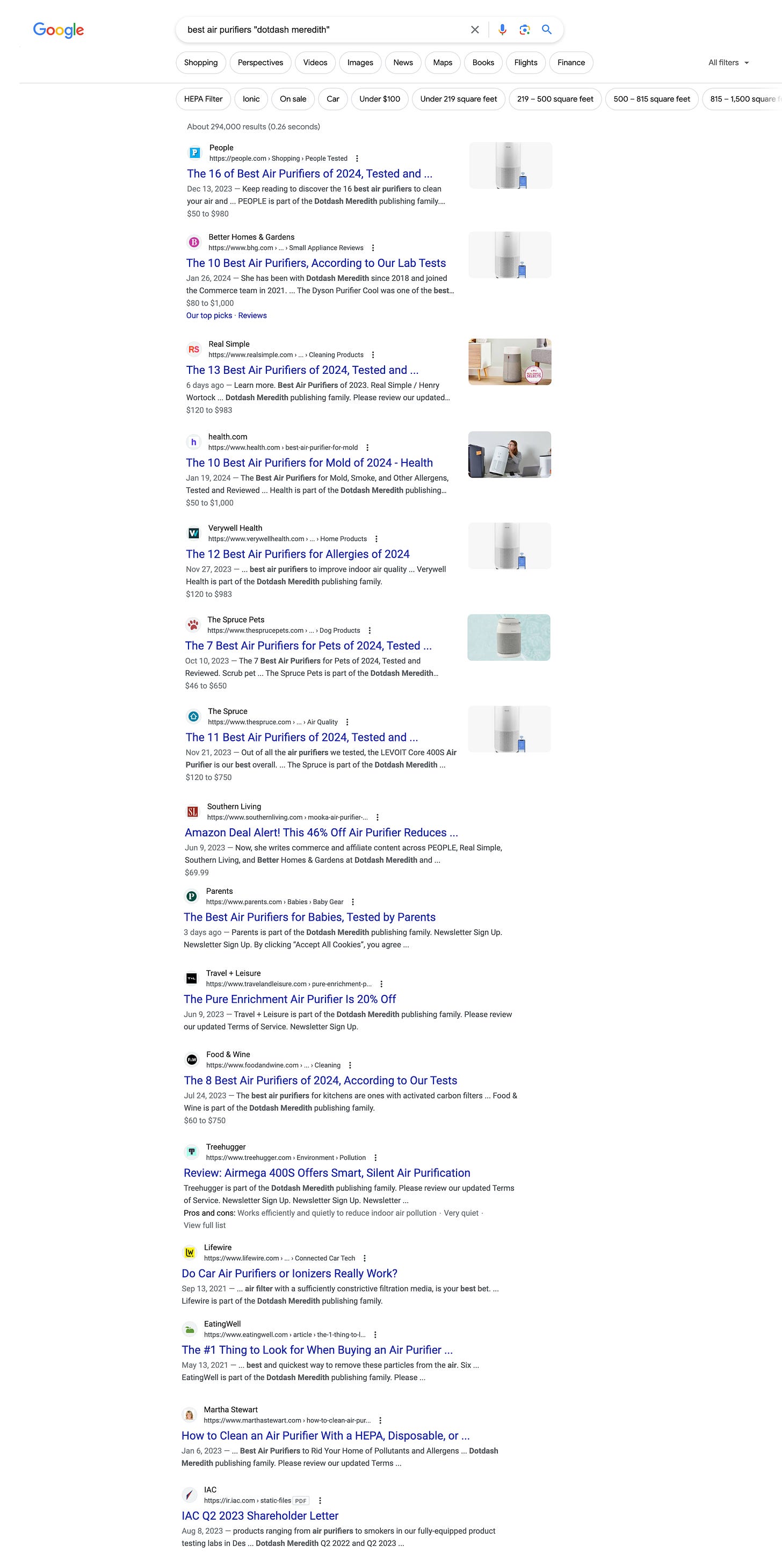

But there’s something else going on here, too. Earlier this year, HouseFresh founders Gisele Navarro and Danny Ashton unpacked how big publishing conglomerates like Dotdash Meredith have adopted a private equity model that “utilizes public trust in long-standing publications to sell every product under the sun” via Google SEO optimization. The end result: sites like RealSimple.com and BetterHomesandGardens.com pump out “best of” product recommendation lists to game Google’s search algorithms.

These recommendations are rarely as reliable as those coming from actual product recommendation sites like Housefresh or Wirecutter — usually because the recommendations aren’t coming from product category experts, just writers who are expected to churn out content. (If you’re interested in this sort of thing, I cannot recommend the entire piece enough — it’s a pretty devastating indictment packed with receipts). These recommendation posts are reverse-engineered (using language like “by experts” in the headline) to surface at the top of results for anyone poking around on Google for “the best air purifier.” The success of this type of post leads to its endless replication: not just across categories (“Best Handheld Vacuum,” “Best Leafblower”) but also across the media conglomerate:

No publication — at least at Dotdash Meredith — is spared. If you read the post, you’ll see that some of the top SEO chum (for air filters, but also all manner of “best” recommendations) is coming from People.com. All of this is pretty grim shit: the result of executives who understand legacy publications, from Popular Science to Sports Illustrated, solely as vehicles for online ad arbitrage schemes with diminishing returns.

●

When I think about People today, I feel myself stepping into the role of the critics who went after the magazine in 1974. They thought Time Inc. was tarnishing its good name — and that the magazine’s success, as President Jimmy Carter put it, confirmed a sense “of a nation whose familial values are in trouble and whose morals are in decline.” But so much of the reaction to People, particularly in the ‘70s, was contextual. It gleefully pledged to avoid politics entirely. Its sections were given titles like “Sequels,” “Winners,” and “Happy.” When People’s editors declared that the magazine “embodied an editorial idea whose moment had come,” they were speaking to broad disillusionment with political life in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s and its dominance of the media landscape.

There’s a sad kind of symmetry to our current moment. Twitter is a sad shell of its former self; Facebook is just groups; Instagram is lifestyle content; TikTok is storytime; network television is on life support; cable news’s doomsday clock is ticking; the podcast industry has imploded. There’s palpable fatigue with the never-ending stream of bad news that’s seemingly always getting worse. Ryan Broderick calls our current online landscape “the quiet internet” and that feels appropriate. Nothing makes a sound, certainly not a collection of vaguely bourgeois web brands farming SEO and affiliate dollars.

But People should be thriving in 2024. It could be an antidote to a breakneck 24-hour news cycle, the beating quasi-journalistic heart of a world still deeply fascinated with the lives of celebrities and the lives of the normal people who become the stars of the day’s internet. Everyone is so incredibly available and producing content! These are perfect People conditions! It could be as robustly staffed as the New York Times!

But if People Magazine embodied an editorial idea whose moment had come, then People, in its current iteration, embodies an editorial idea whose moment has passed. It has been devoured by its young. An era of exclusivity and access journalism gave way to both celebrities and normies going direct. In a world where everyone is incentivized to behave as if everyone else is watching and to communicate as if they’re operating their own one-person public relations firms, a publication like People is reduced — by the sheer volume of it all — to the role of an aggregator.

But access and exclusivity aren’t the only editorial moments that have passed. People is also a casualty of an internet where a magazine doesn’t really make sense. More specifically, it’s a casualty of an internet where collecting stories about people — famous and not — doesn’t make sense. That’s what platforms do: TikTok, Reddit, Instagram, they’re constantly amassing stories and curating them to your needs. Jennifer Garner is on Reels, and so are Drake and Kendrick Lamar. Oh, and the “nun with herpes” — as Jann Wenner once derisively referred to People Magazine’s primary mode of human interest content — well, she’s there too, along with all the other ordinary people with extraordinary stories, producing content that People will collect and put next to its updated post on “The Softest Sheets of 2024, Tested By Real People.”

Today, I look at People.com and see every other Dotdash Meredith Property. They’re nearly indistinguishable from each other — and from every other site trying to sell my demographic something on the internet. I don’t see any of what made People feel alluring or even objectionable. In truth, I don’t see the past at all. But I do see the future. ●

Subscribing gives you access to the weekly discussion threads, which are so weirdly addictive, moving, and soothing. You can find all previous threads here, if you need that enticement.

Plus! Subscribing is how you’ll get the Weekly Subscriber-Only Things I’ve Read and Loved Round-Up, including the Just Trust Me. It’s also a very simple way to show that you value the work that goes into creating this newsletter every week.

As always, if you are a contingent worker or un- or under-employed, just email and I’ll give you a free subscription, no questions asked. (I process these in chunks, so if you’ve emailed recently I promise it’ll come through soon). If you’d like to underwrite one of those subscriptions, you can donate one here.

If you’re reading this in your inbox, you can find a shareable version online here. You can follow me on Instagram here — and you can always reach me at annehelenpetersen@gmail.com.

Thank you for explaining the origins of The Spruce! I've been puzzling over its weird affect for a while now.

Side note on About.com: I freelanced for an About in the late aughts, to about 2013. (I launched and ran the culinary travel coverage, this after about 15 years of writing for top tier magazines.) I get why you used scare quotes for “articles,” and the quality on the site certainly did vary — but by the time I came on it was hard and competitive to get hired, and there was a lot of oversight and support to create quality content. (This was the time when it was being prepared for sale, which likely accounts for a lot of that.) I do understand that there plenty to mock about the site — it looked terrible for one thing — but when I was there, the people who were hired to run their topic areas —whether it was IBS or rollercoasters—were genuinely passionate about their subject and worked hard to make good content. (About was also often confused with similar and way more crappy sites, which often leads to more shade and tarnish than deserved.) With that perspective said, thanks for such an interesting read as always! I had no idea that I’d be reflecting on my About.com time when I woke up this morning. :)