Do you find yourself consistently opening these emails? Do you come back to them or forward them or think about them over the weeks to come? Do they spark conversation in your group chat??? If you value the work here, consider subscribing.

You’ll get access to the weekly Things I Read and Loved at the end of the Sunday newsletter, the massive links/recs posts, the ability to comment, and the knowledge that you’re paying for the stuff that adds value to your life. Plus: the Culture Study Classifieds (why can’t I stop reading them) and last Friday’s enormously useful Peri/Menopause Brain thread.

**And make sure and check out the new episode of with Caroline Moss, all about the *weirdness* of the online shopping experience, better ways to shop online, and antidotes for anxiety shopping. Listen here or wherever you get your podcasts.**

I’ve spent a lot of time changing my mind about Anne Hathaway. She bugged me; I interrogated why she bugged me; I ended up writing about Anne Hathaway Syndrome — aka, “when you do everything right and society hates you for it.” The more I’ve thought about it, the simpler it becomes: Anne Hathaway is and was a theater-kid with theater-kid earnestness during the crescendo of the Jennifer Lawrence cool girl era. She annoyed people for the same reason Taylor Swift rapping/dancing around to “Shake It Off” at her Yahoo live album premiere annoyed people. It was cringe to be that joyful in your own fame.

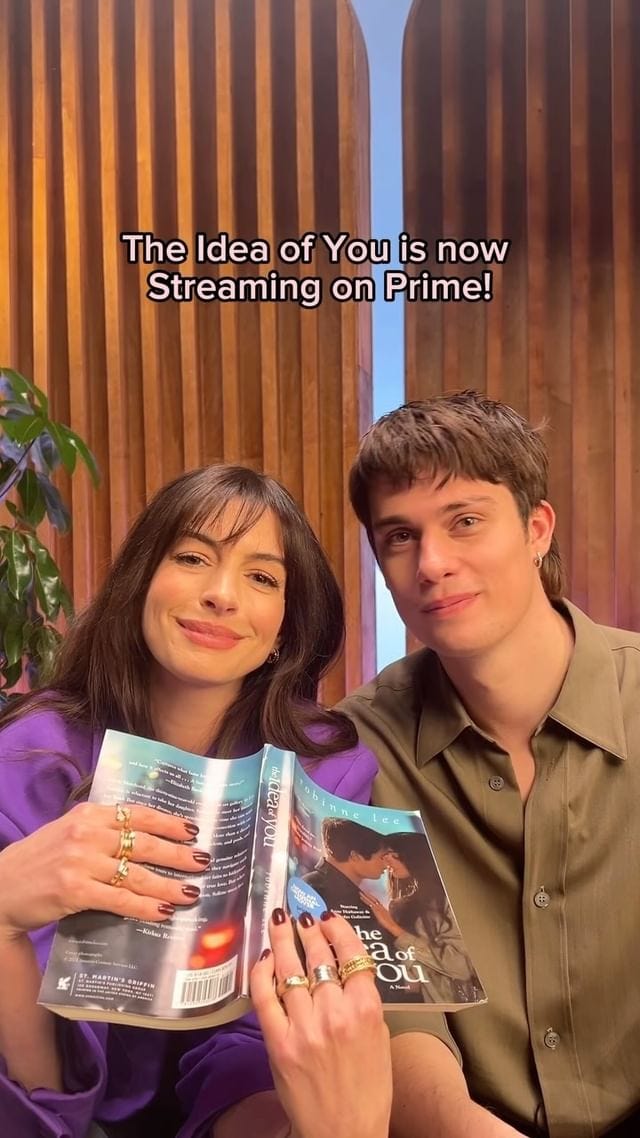

Fastforward a decade, and Hathaway is the star of The Idea of You, an adaptation of a (pretty hot) novel that documents the relationship between a woman whose husband has left her and a much younger singer in a One Direction-style boy band (who she meets when she takes her daughter to the concert; crucially, the daughter’s favorite member of the band is not the focus of the relationship). When the book first took off during the pandemic, there were immediate comparisons to Olivia Wilde and Harry Styles, as if the book itself were a sort of fanfic. But that oversimplifies the book (and the movie), which both do something complicated with the protagonist’s desire (and self-development).

The Idea of You premiered on Amazon Video earlier this month. In previous eras, that would’ve told you it was a stinker; in today’s Hollywood, it just means it’s not a cartoon, a blockbuster, a horror movie, or Oscar bait. It’s a movie (largely) for women of a certain age! But that doesn’t mean this isn’t a big-deal movie. (It’s very difficult to measure streaming data alongside box office grosses, but The Idea of You was the #1 streaming movie for May 3-9th).

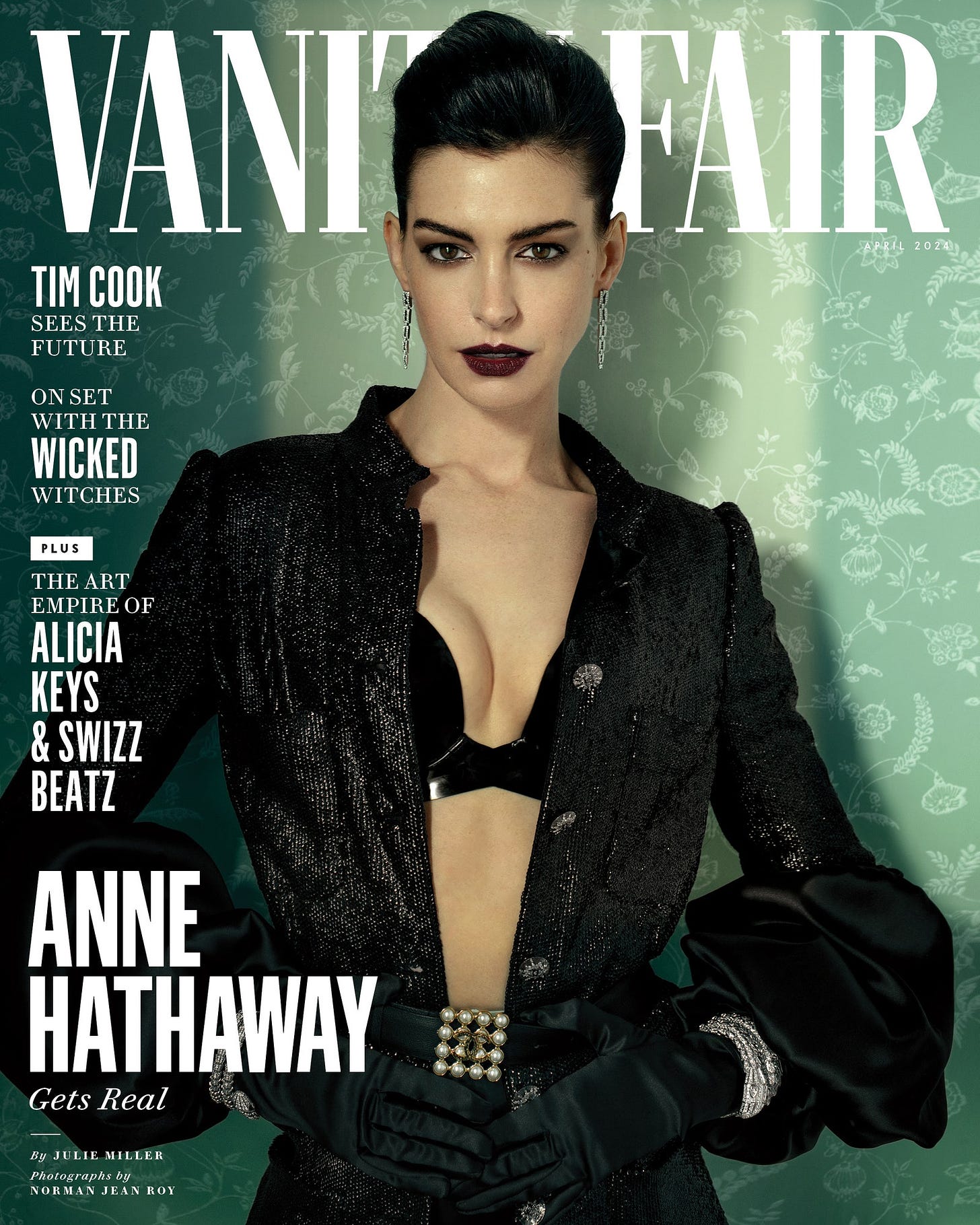

Hathaway’s PR team successfully engineered a publicity campaign out of a different era, with a stunning Vanity Fair cover shoot to accompany an in-depth profile with disclosures that were picked up and broadcast across the celebrity gossip press (in this case, that she had a miscarriage in 2015 while portraying a pregnant woman in the Broadway play Grounded).

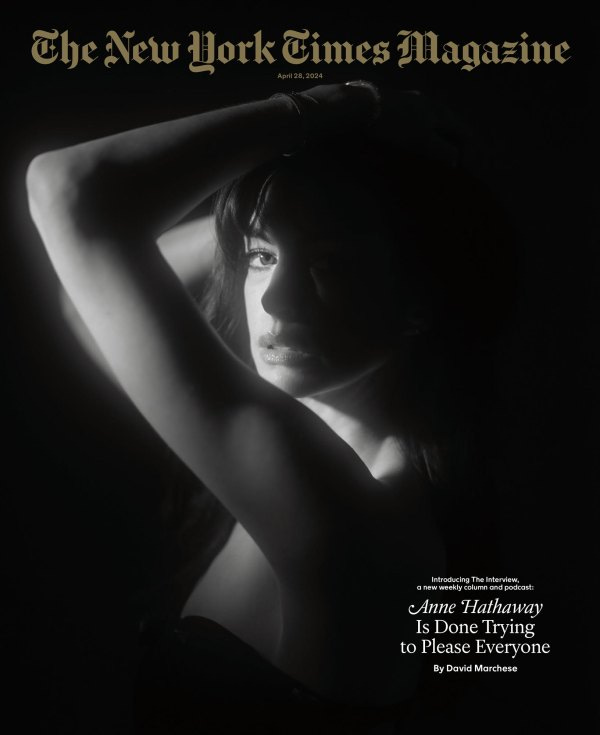

Hathaway was also on the cover of the New York Times Magazine, sat for an in-depth interview with David Marchese, and did a high fashion conceptual shoot for V Magazine. And, of course, she did the usual talk show circuit and posted a bunch of highlights of the press tour to her (well-cultivated) Instagram.

Every celebrity publicity campaign has a purpose. Getting you to go consume the thing the celebrity is promoting, sure, but it’s more than that. Sometimes the goal is to underline just how much preparation and work went into a role, creating an aura of “serious acting” (and awards viability) around a role. (See: most stars who “go method,” especially for the first time). Sometimes the goal is to smooth a mild scandal, or to narrativize a new relationship, or add texture or friction to an otherwise banal image (especially true with new and emerging stars, whose nascent images are usually just: hot).

An effective publicity campaign is well-paced, so that information and images from a first appearance (in Hathaway’s case, Vanity Fair) can cycle through the internet before information and images from the second appearance (New York Times Magazine) appears. In many cases, particularly if they’re handling a massive star, there will be significant negotiations over which story is released first (print magazines almost always get first position — and even though Vanity Fair has less power and heft than it once did, it and Vogue are still considered the #1 gets). There will be talking points, postures, and agreements as to what the star will and will not talk about, but the goal is for readers to come away from a publicity cycle with a certain feeling, a certain understanding, of who the star is now.

Anne Hathaway has an excellent publicity team, which is not unrelated to Anne Hathaway being a very good celebrity. But as I read these interviews — which are pretty compelling, as contemporary celebrity interviews go — I started wondering: what, exactly, is Anne Hathaway (and her team) trying to tell us?

1) Anne Hathaway is Sexy

This is the very obvious message of the Vanity Fair images. They’re shot by Norman Jean Ray, best known for moody, alluring celebrity photography like these shots of Jeremy Allen White. They’re preparing us to understand: Yes, Anne Hathaway is a mom now. Yes, her previous image, built on the solid foundation of The Princess Diaries (dork turned glam) and The Devil Wears Prada (normie navigates fashion) was “not sexy.” But This Anne? Sexpot. Having hot sex with a hot younger guy! (IN THE MOVIE!)

The subtitle of the profile makes it explicit: Hollywood used to tell her she wasn’t sexy. She knew better: “I was like, ‘I’m a Scorpio. I know what I’m like on a Saturday night.’”

When I first read that, I cackled. WHAT DO SCORPIOS DO ON SATURDAY NIGHTS?!? Do I not know because I’m a Taurus?!? PROBABLY! But this is the way Anne Hathaway is now sexy: through suggestion, through absence. You don’t need to see her naked when you have a form-fitting translucent rubber dress (or beautifully androgynous and fully clothed over at V).

The hardness of both sets of images also contrasts with the soft, sultry quality of the cover shoot for New York Times Magazine:

The title of the piece is doing some explicit work: “done trying to please everyone” isn’t “I’m not your good girl” but it’s not not that. Then there’s the tousled hair, the exposed skin, the open mouth, the direct stare — if the Vanity Fair shoot was “Scorpio on a Saturday night” then I guess this is Scorpio on a Sunday morning?

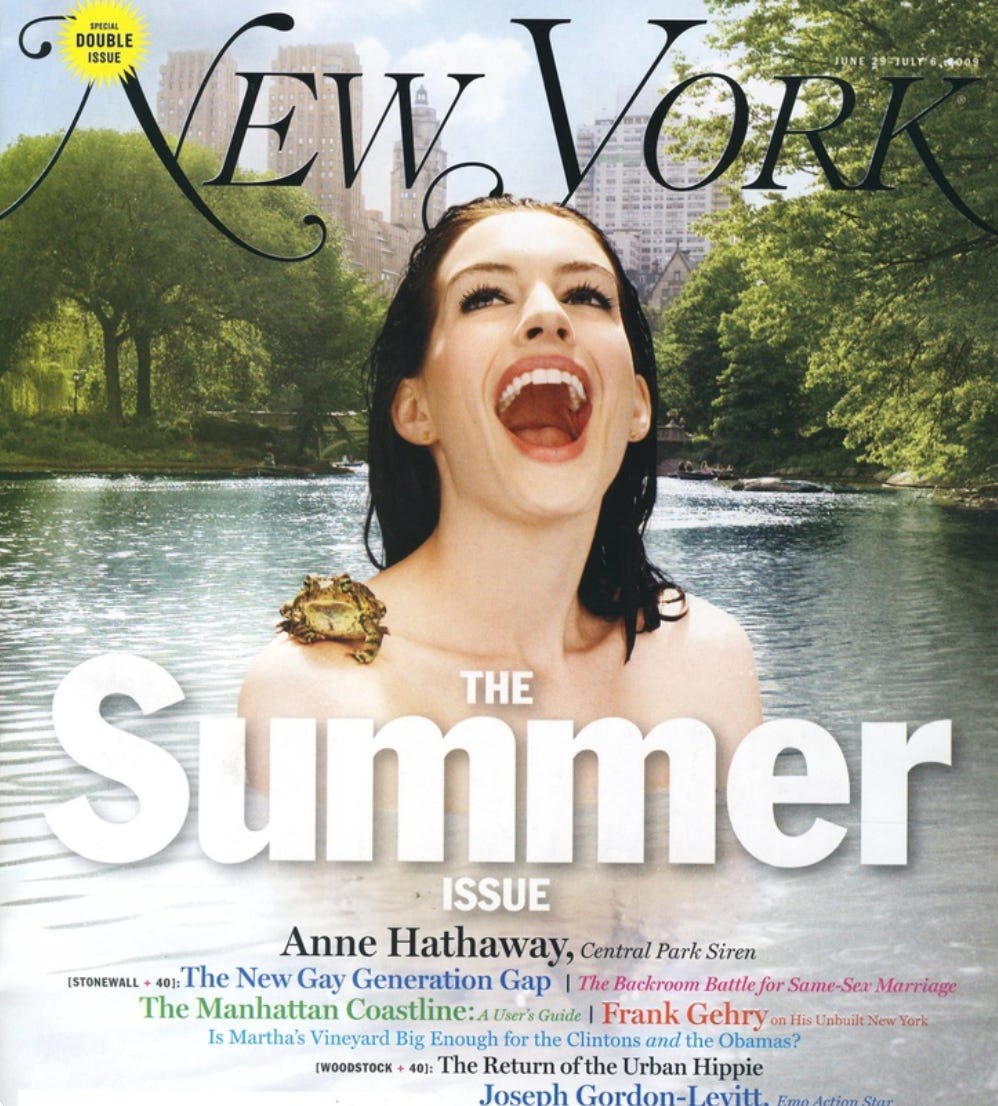

Contrast these looks with this 2009 cover shot for New York Magazine:

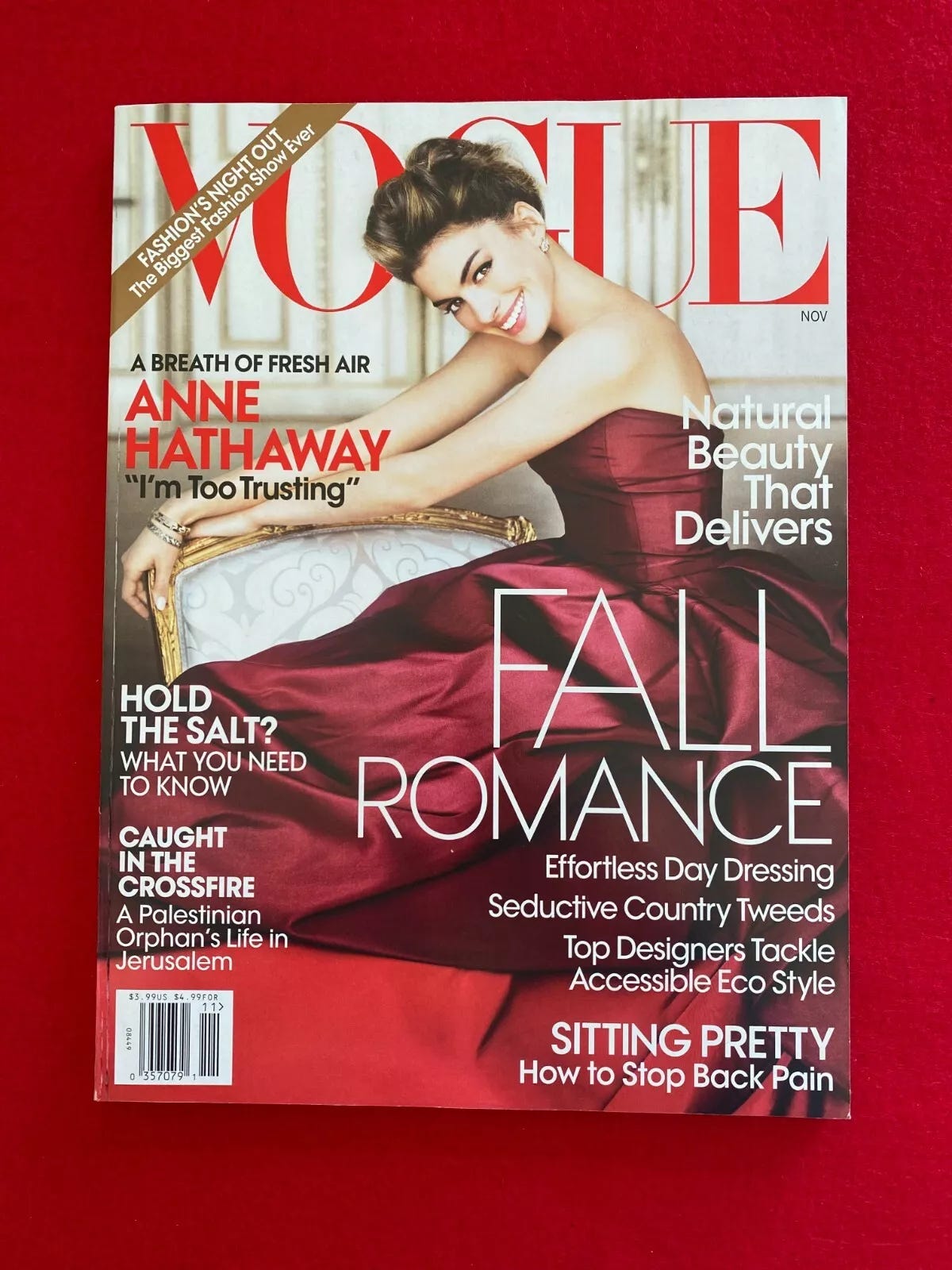

Or this cover for Vogue in 2010:

She’s always gorgeous, of course, but the first cover exudes dewy innocence, and the second, well, it’s very 2010 bridal glam. Beautiful, not hot. And then there’s this:

Entertainment Weekly has never been great at sexy, but this cover promoting Love and Other Drugs? Somehow it looks like a Viagra ad.

Older Anne Hathaway is Hotter, Sexier, Bolder than that Hathaway. You could see a hint of it in this 2022 cover for Interview. But in 2024, her team understood that in order for The Idea of You to work, the sex with a boy band star needed to not seem cringy, and for that to happen, you needed to feel comfortable looking at Anne Hathaway, knowing she was a mom, and *also* thinking sexy. Hence: a lot of oblique discussion of parenting in the text, and a lot of hot imagery alongside.

The problem, as Cat Zhang argued earlier this month, is that Hathway might now be too hot for this movie to really work. Classic case of Hathaway syndrome, because she would obviously also get roasted if she was “too Mom” for it to be believable. But I do think this campaign and role have been successful enough that it could (could!) open a new lane for her…..if the studios decide to keep making movies in that lane.

2) We Made Anne Hathaway Feel Like Shit

I include myself here because the author of the Vanity Fair profile explicitly links my Anne Hathaway article, situating it as part of Hathaway’s long history of “a woman pushing against societal expectations and getting a lot of grief for it.” Here’s the table setting:

More than a decade ago, around the time she won an Academy Award for her work in “Les Misérables,” the online commentariat turned on Hathaway for … who knows, exactly? Some strange groupthink kicked in that caused people to pile on her for seeming like an inauthentic striver — or something. Other than as a case study in the inexplicable and random cruelty of the internet, the whole phenomenon, described at the time as Hathahate, makes even less sense now than it did then.

To be fair, the dislike always made sense — if pressed, people would tell you exactly why they disliked her image! — it’s just that it made and continues to make shitty sense, rooted in punishing understandings of how women should behave in public. For women, the dislike also often involves a lot of internalized misogyny — and a fair amount of self-loathing. That was true for Hathaway, too: “This was a language I had employed with myself since I was seven,” she said in 2022. “And when your self-inflicted pain is suddenly somehow amplified back at you at, say, the full volume of the internet…. It’s a thing.”

Hathaway also makes clear that the dislike directed her way so thoroughly inflected her image that she was passed over for roles. It forced her, as she told David Marchese, to develop scar tissue. And now….

3.) Anne Hathaway is Not That Nice

She’s given up being a people-pleaser, because all that did was make people dislike her. But part of the problem was that she didn’t really even know who she was, other than someone who tried to make people like her (fellow people-pleasers, this might be highly relatable). As Hathaway puts it in New York Times Magazine,

So much of the reason I was drawn to acting is that it was an outlet for expression that I could not find on my own. And in the space between feeling so connected when I was acting and so lost when I wasn’t, you try to make your way, and one of the ways that you make your way is, “Oh, if I do this, that will make someone else happy, and maybe that’s what I’m supposed to be doing.” It takes a long time to go, “That doesn’t really matter if you don’t know who you are.” Unless you just want an identity that’s all about pleasing people. Which I suppose is perfectly valid. But I’m not that nice.

“But I’m not that nice!” Wonderful, I love it, even though it’s undercut by every video of Hathaway I’ve ever seen being a very nice and accommodating person to everyone in her orbit. See:

Still, this declaration, coupled with “Scorpio on a Saturday night,” is essential to decentering niceness at the core of her image. Where that niceness was, now there is scar tissue. But not too much, because….

4.) Anne Hathaway is Not Armored

When Hathaway first rose to fame, she tells VF, the leading advice was that you had to create a public and private self — and boundaries between the two. “I found that terribly confusing,” Hathaway said. “So I don’t do it that way. I’m not armored.” In other words: all of our criticism and vitriol could have curdled her personality. But instead, she’s found her actual sense of self, kept herself soft and vulnerable — and just made it much more difficult for others’ dislike to directly affect her.

She says she doesn’t go online. And she’s very careful about how she speaks to the press. You can see the shape of it in the Vanity Fair profile, where Hathaway uses the power of disclosing that vulnerability to keep the conversation anchored there…..while also expressing anxiety over the entire form of the profile, and how poorly she translates in it. (“She’s not as serious as interviews make her seem, she tells me, but as we first start talking at least, she’s definitely careful — present and engaged but also pausing to mentally scan answers for web-flammable sound bites before sharing them.”)

You can see the carefulness made explicit in her conversation with Marchese, which includes several different points where she calls attention to the ways in which she’s choosing to speak with great care.

To start:

Marchese: You haven’t done a romance in a while. Can you talk to me about why you wanted to do “The Idea of You”?

Hathaway: It’s such a softball question, and I can feel my brain complicating it.

And then:

Marchese: I have a hunch that maybe you’re a ruminator. Is there anything about our conversation to this point that you’ve been thinking about?

Hathaway: I had a slight word-choice remorse moment. You asked me what my goals are and I decided not to share them and the reason I gave was because I’d rather not have them “shredded.” That seemed a little harsh. I regretted that.

And also:

Hathaway: You know what it does? It puts me in a defensive position. Not defensive in the sense that I feel attacked but defensive in the sense that it’s hard to say something revealing with a tape recorder there. So I feel like I become a more self-conscious, more neutral version of myself. I watch other actresses, and they’re so free, they’re so off the cuff. Not that they’re more revealing, they’re just — I don’t know. I don’t have a word for it. We don’t usually ask people such direct questions. That’s not the way conversations are usually built. Normally trust is established by sharing something about ourselves and you build up a mutual understanding. So a part of me just resists the form of this.

All of which allows us to remember that….

5.) Anne Hathaway is a Very Good Celebrity

Evasive stars come off as assholes in interviews. Careful ones come off as banal. What Hathaway is doing here — wielding past mis-reactions to both insulate her from future ones and normalize her reticence to engage — is incredibly skillful. She manages to come off as hardened but soft, unwilling to take others’ shit but kind, hurt but strong, nurturing but sexy. The antagonist of Eileen and the protagonist of The Idea of You. The best celebrities, the ones that endure, are those who can successfully embody those sorts of contradictions.

I can acknowledge all the ways the criticism of Hathaway’s previous image were misogynistic and unfair, and I can also understand that part of the reason her image was so susceptible to that critique was because of its flimsiness. There was no tension. She was just great, and grateful, and it just wasn’t enough — in part, as Hathaway admits, because there was so little sense of self other than that desire to be liked. Part of growing into yourself is figuring out who you are. And part of growing into yourself is figuring out that you are many things.

In the sprawling document I used to organize passages from all the interviews Hathaway did over the past few months, one of the subheadings is REAL PORTAL ENERGY. In one passage, excerpted from her interview with V Magazine, Hathaway describes what drew her to the role in The Idea of You. It seems appropriate to end with it for many reasons — not least of them the fact that it’s Hathaway, not me, who’ll get the final word:

“[My character’s] going through a moment in her life when she is on the verge of becoming bitter,” Hathaway says. “She experienced a trust trauma. And a trust trauma is a hard thing to come back from; all that sweetness is beginning to sour. That’s not a role I could have played on day one of my career….One of the points that the movie makes is something that really resonates with me: We have limited ideas of appropriate ways for women to be happy. And we react harshly and punitively when we feel that women have stepped outside those boundaries. I think that needs to stop, so I made a movie about it.” ●

How have your own Hathaway feelings changed? What other celebrity’s have successfully textured their image over time? How *does* a Scorpio behave on a Saturday night? Tell all, but as always: don’t be assholes (about Hathaway, about others’ feelings about Hathaway) and let’s keep this one of the good places on the internet.

Subscribing gives you access to the weekly discussion threads, which are so weirdly addictive, moving, and soothing. You can find all previous threads here, if you need that enticement.

Culture Study is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber

Plus! Subscribing is how you’ll get the Weekly Subscriber-Only Things I’ve Read and Loved Round-Up, including the Just Trust Me. It’s also a very simple way to show that you value the work that goes into creating this newsletter every week.

As always, if you are a contingent worker or un- or under-employed, just email and I’ll give you a free subscription, no questions asked. (I process these in chunks, so if you’ve emailed recently I promise it’ll come through soon). If you’d like to underwrite one of those subscriptions, you can donate one here.

If you’re reading this in your inbox, you can find a shareable version online here. You can follow me on Instagram here — and you can always reach me at annehelenpetersen@gmail.com.

![Jake Gyllenhaal - Entertainment Weekly Magazine [United States] (26 November 2010) Jake Gyllenhaal - Entertainment Weekly Magazine [United States] (26 November 2010)](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F1a982f84-f111-43f5-82ed-b3abd262cc0e_454x607.jpeg)

I haven't watched The Idea of You yet, but I've always liked Anne and was always confused by those who didn't. I could see if she had said something obnoxious but as far as I know, she hasn't. I really think it boils down to the fact that America hates a woman who tries hard and is open about the effort she puts forth. (You can often see that with female politicians, too. Women are either trying too hard to be the center of attention OR are not working hard enough.)

It's interesting that there was also a backlash against "cool girl" Jennifer Lawrence (who I also like—she has a wicked sense of humor). Women in the spotlight have it really hard, so I'm glad Anne doesn't look at social media. In fact, I've mostly stopped myself and I'm not even close to famous.

Those videos of Anne's responses in the past to all the male journalists asking her about her weight are priceless. Who would not like that person?! She's quick and funny and slapping them down in a way that won't get her called a mean bitch.

Hathaway committed a cardinal sin of femininity by being a “striver.” To achieve the feminine ideals one must work—a lot, femininity takes a lot of work—but you can never let the effort show.

When Hathaway hosted the Oscars with Franco you could see her valiantly working to rescue that hosting gig from Franco’s spaced-out indifference. But America loathes a striver, especially if that striver is a woman.