What Makes Women Clean

"Men are socialized to see their spaces as utilitarian, spaces that serve them. Women, we serve our spaces."

This piece took a lot of work — and I’m committed to making it available to everyone. That’s only possible because people believe in subscribing to this project — and thereby making it possible for this piece to be accessible to all.

Subscribing also gets you access to threads like Tuesday’s Make the Case for the Best Soundtrack (ridiculously nostalgic) and Friday’s meditation on Theories of Resilience. If you want to be hang out in one of the remaining good places on the internet, consider joining us.

Not all women like to clean or even prioritize cleaning. My friend group in college was neatly and hilariously divided on this point: half were pretty neat. The other half, let’s just say they found themselves wearing swimsuit bottoms as underwear a lot. They were just as smart, accomplished, and hot. They just had larger piles of laundry.

It doesn’t matter if you keep a clean space or you don’t — you nonetheless understand how society understands and elevates cleanliness. Cleanliness is morally superior, and women should aspire to be morally irreproachable so as to negate the original sin of being a woman. An unclean woman is a bad woman; an untidy house reflective of an undisciplined mind. You can understand this thinking as bullshit and still be subject to it.

How else do we explain just how much extra time women spend attending to their homes? Many women struggle mightily to clean, or think it’s a waste of time, or find cleaning difficult. And yet they still do so much more of it.

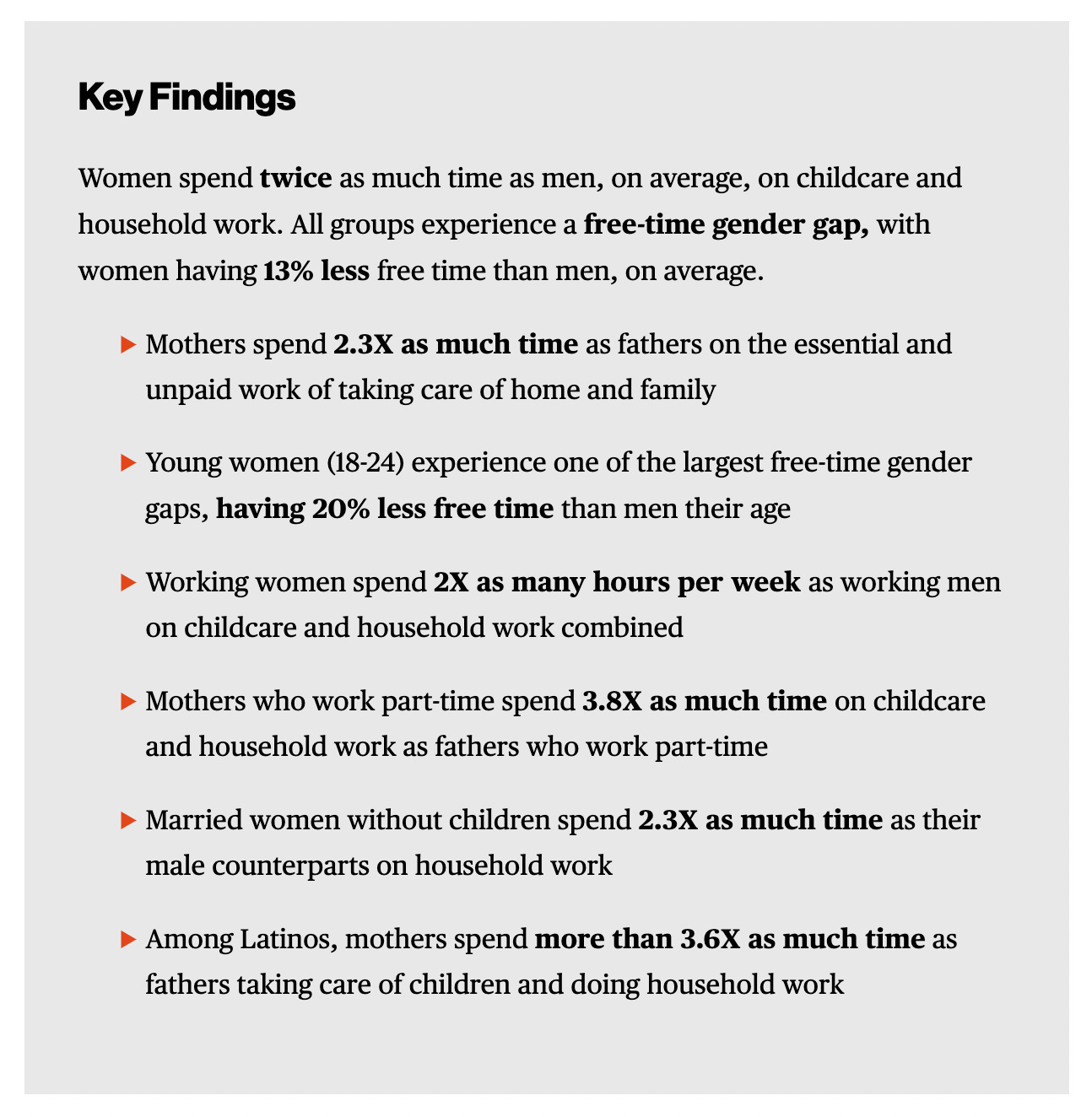

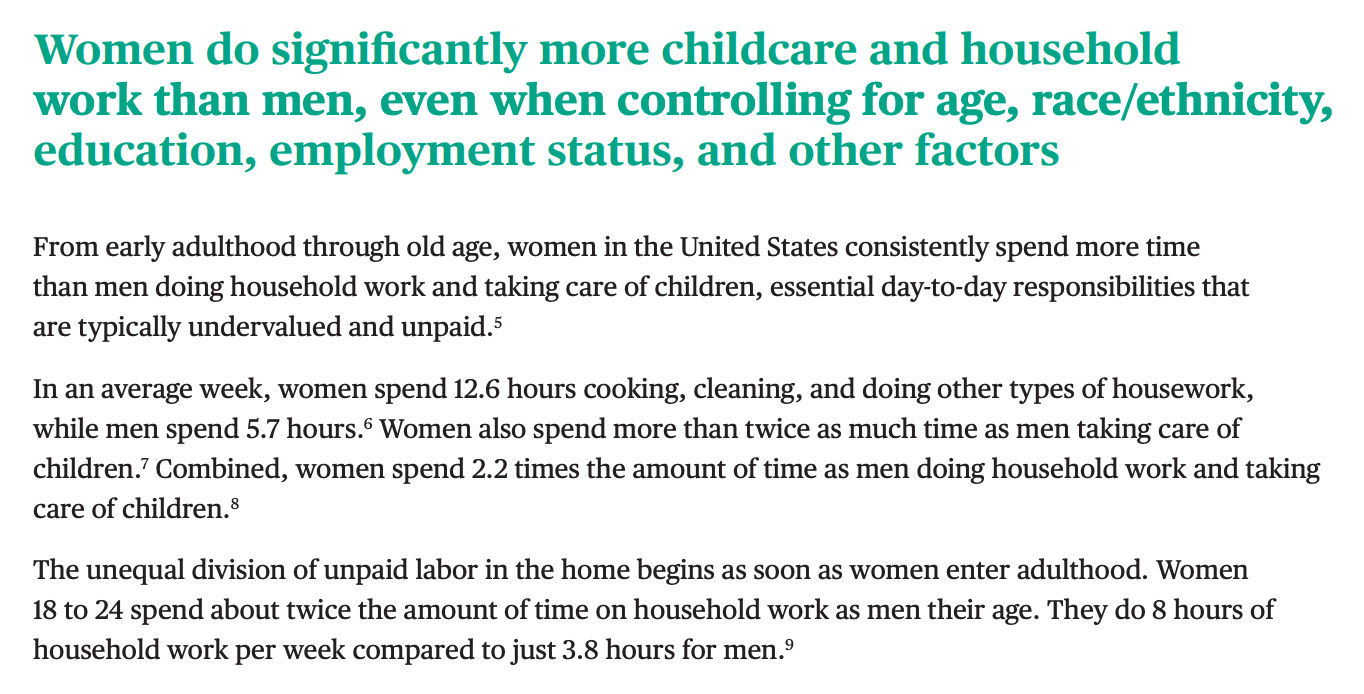

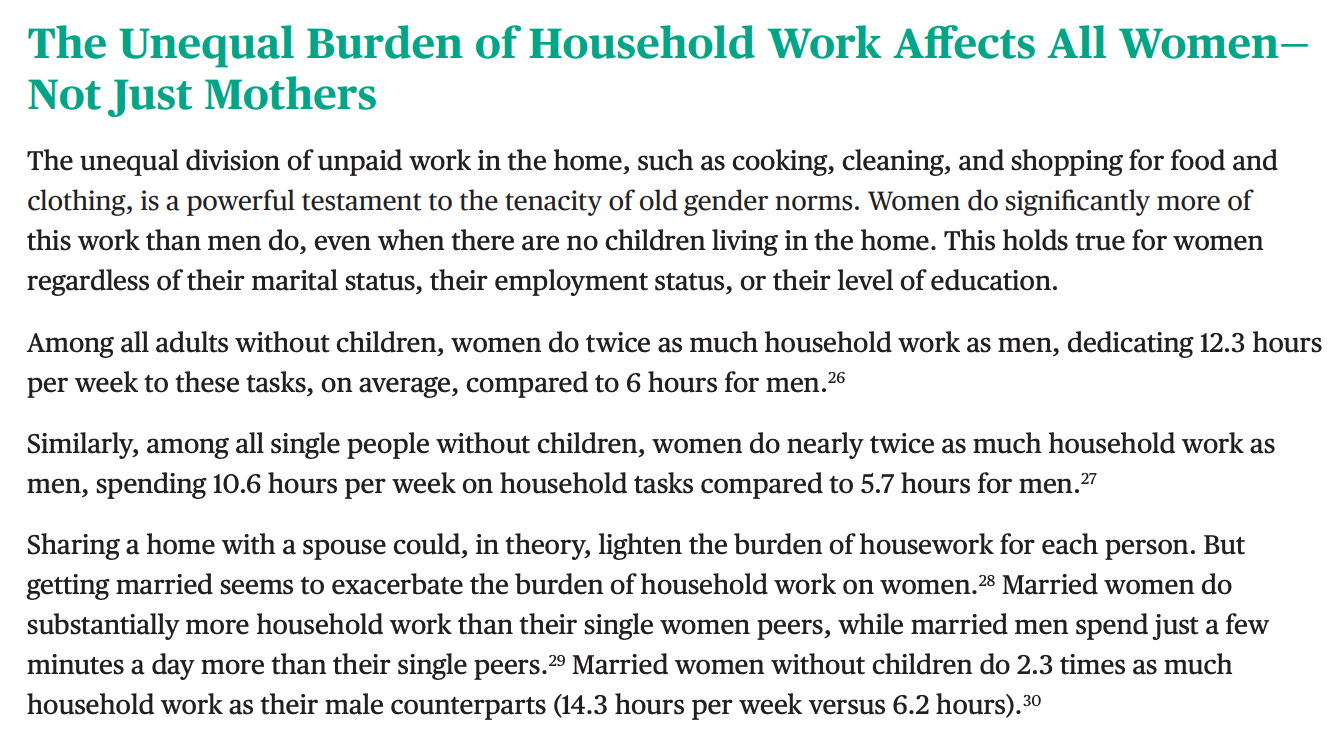

Earlier this month, the Gender Equity Policy Institute released a new analysis of the 2022 Time Use Survey, administered by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. The Time Use Survey is not perfect or granular, but it’s widely understood as the best and broadest data set of how Americans allocate their time. The survey asks respondents where and how they worked, how much time they allocated to childcare and/or domestic tasks, and how many hours were dedicated to “leisure.”

You can take a closer look at the survey methodology and results here — and while they do breakdown results by race, age, income, education level, marital status, occupation, and number of children in the household, they do not distinguish between heterosexual and queer relationships (and also divide gender as male or female)….which means this analysis does not account for how queer relationships, in so many meanings of the word, fit into this larger analysis.

With that said — the findings are stunning.

This is wild! Working women spend twice as many hours per week on household tasks than working men! You could attribute this stat to shitty heterosexual dynamics, or shitty understandings of who becomes the “primary” parent in a two-parent home, or even chalk it up to how many more working single mothers there are out there than working single dads. But wait!!!!

Look at that stat for 18 to 24 year-olds: more than twice as much household work. As 18 year-olds!

And then here’s the real kicker:

Again: women spend more than twice as much time allocated to household work than men, even when they are single or do not have children. And getting married doesn’t split the load for women, as it theoretically would, but increases it: married women without children still do 2.3 times as much housework labor as their husbands.

How do you make sense of the fact that girls and women spend so much more time on domestic labor? The first strategy is naturalization: women naturally like things cleaner, simply because of our chromosomal makeup. We naturally notice dirt, whereas men do not. As one person put it to me on Instagram when I posted the figures above:

It might have something to do with our periods and the fact that we become an open wound for a bit of time after having kids, being way more vulnerable to bacteria, infection, etc. As long as men don’t step into a rusty nail, all’s good, whereas for women there’s a long history of childbirth/period infection and death especially prior to antibiotics. It might be that cleanliness was essential for our survival, so we learned how to do it properly.

This genre of story is very easy to believe. Similar arguments around women and multitasking/executive function abound: men just had to hunt, but women back at the cave had to tend fires and care for kids and tan animal hides blah blah blah etc etc etc. These narratives make the nonsensical make sense: how else would you explain dramatically different approaches to cleanliness that seem to be fairly neatly divided by gender? It has to be biological, otherwise, well, women have just been caring about things that ultimately matter very little for centuries.

I understand that humans animals with biological adaptations. But I also understand that this particular argument falls apart when you consider women who aren’t “naturally” good at cleaning, or multi-tasking, or even caregiving — or just don’t like it. (Hello, all the ADHDers in my DMs also responding to these stats). Within this framework, the only way to conceive of these women is as faulty specimens: people who would be weeded out by natural selection. And yet somehow these people are still here, being women!

“Everything we call a sex difference, if you take a different perspective — what’s the power angle on this — often explains things,” neuroscientist Lise Eliot tells Darcy Lockman in All the Rage. “It has served men very well to assume that male-female differences are hard-wired.”

Still, a similar argument pops up when women frame their cleaning (and organizing) as “fun,” or a hobby, or something they do “because they like it.” Again, I get it: cleaning can be pleasurable the same way that popping a zit is pleasurable. It’s gross but oddly cathartic to erase abjection and mess, or to create order out of chaos. But you cannot separate the pleasures of degreasing the stove top from the pleasures of successfully meeting the demands of proper performance of womanhood. It’s like people who say they “just like being thin.” So much of why you like it is because it grants you societal power.

And also: men can clean! I know men who are good at it, who take pleasure in it, who are also excellent noticers and multitaskers — and almost all of them were either 1) raised by single mothers or 2) spent time in the military. They were socialized, over an extended period, to understand cleanliness and multi-tasking as essential — with personal and social consequences if they did not.

The truth is all people — men and women — have become very adept at crafting narratives, often rooted in “natural” behaviors, that excuse us from creating substantive societal change. Women aren’t better cleaners or multi-taskers; we don’t “like” it more. We do it, if we do it, because we know that if we don’t do it, chances are very high that our worth will be subtly or pointedly called into question.

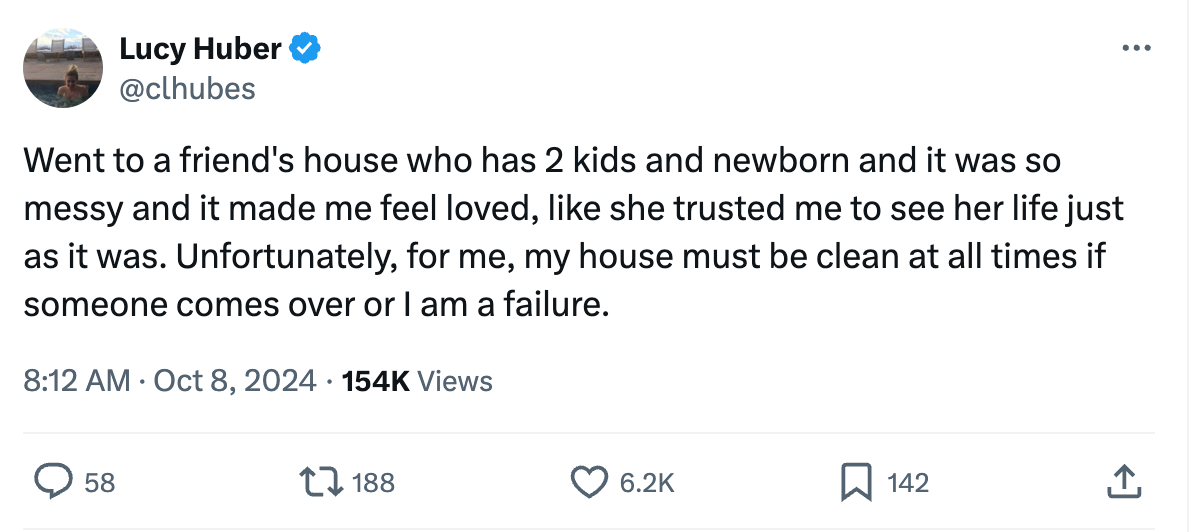

“When people come over and our house is a mess, I feel this reflects badly on me as a person, adult, wife, and mother. My husband doesn't feel that at all,” a reader named Leah told me. “My father-in-law once told my husband he wished our house was cleaner when he comes to visit (don’t get me started). So now I scour the place top to bottom. My husband just shrugs and says: whatever, my dad can deal with it. The same applies to our kid. My husband can send him to school in ripped, dirty, or too-small clothes and not worry what people will think of him and his parenting skills. Me? I’m worried they are about to call CPS on us.”

If you have enough societal privilege — if you’re “safe” being bad at womanhood — you can blow off societal repercussions. But a messy or dirty domestic space intersects with so many other stereotypes of class, race, education level, body size, and marital status. “My grandma grew up extremely poor in the South and I’ve always felt there was a strong class element to her standard of cleanliness,” a woman named Aimee told me. “Like even if you had no money, get a broom and a rag because you at least need a clean house.”

Or: a single woman can have a dirty apartment if she’s a hot, dirty mess; take away the hot thinness and she’s just a slovenly cat lady spinster. As Kels put it, “when you're a woman living alone without kids, it really feels like there is cultural pressure to keep a clean home because you are perceived to have so much more free time and the cultural expectation is that time should be put into the home.”

I personally don’t believe this! I don’t think most people believe this! Yet these understandings endure, asking women to feel like failures or oddities, setting up shop in our relationships and slowly festering. And women are often doing the most effective policing of other women, in part because we are so accustomed to policing ourselves.

“I wonder how much of [all this] is just generational trauma being passed down,” a woman named Laura wrote to me. “Our moms were taught this stuff and so we grew up only knowing a peaceful house when it was pristine, because otherwise she was cleaning. Now, we can’t feel at peace until it’s clean, even though there isn’t anyone telling us it has to be this way.”

Maybe your mom wasn’t a super clean person, but still occasionally rage cleaned or raged at you to clean. Maybe your house was dirty and you never felt pressured to clean, but societal norms made you yearn for a mom who did, and now you’re that mom. Or maybe your mom lived and died by the cleanliness of her kitchen floor — and you can feel her eyes on every inch of your home.

I’m talking about clean culture here, but I could also be talking about diet culture, and morality policing, and mom-shaming. I also don’t know how much I blame women in these scenarios: so much of this policing is the result of trauma, rejection, and shame. At the same time, I do think many of us operate, knowingly or not, as agents of harm. It is tremendously hard to divest from a way of understanding your own value in the world — and, by extension, others.

Maggie put it this way in a DM: “I remember getting my first college apartment and being so excited to decorate and make a cozy little place to call my own. But with that self-expression of decor comes the onslaught of cleaning and upkeep. Especially when I was young, it felt like social media was constantly showing me new ways to upkeep with my space that suddenly seemed absolutely necessary (I don’t think my mom ever mopped her walls, but apparently I’m supposed to!) Men are socialized to see their spaces as utilitarian, spaces that serve them. Women, we serve our spaces.”

We can attempt, as a society, to socialize boys and men to be more clean, to notice more, to multitask more, to spend more time on domestic tasks and to allocate less time to leisure. We can teach men that their value (and their morality) is also rooted in their capacity to maintain a clean home: that they should also serve their spaces. We can convince men in heterosexual relationships that domestic labor is not uniquely the providence of women. And to be fair, some of this work has happened: men in their 30s and 40s today do more domestic labor than their grandparents or great-grandparents did. But the gender discrepancy in domestic labor closed and closed and then….got stuck at a 65/35 split, and hasn’t budged in years.

The math just doesn’t math when it comes to domestic labor. When dads start allocating more time to parenting, it doesn’t subtract from the time moms spent parenting. When women leave the home to work for pay, the number of hours they allocate to domestic tasks doesn’t decrease, as one might assume, but goes up. If men do more, women still…..do more.

The bar is too damn high. The norms are too hungry. Even the idea of being able to achieve perfection in all things — in home, in career, in parenting, in appearance — is too normalized. The tireless pursuit of self-maintenance, of regimentation, of renewal and redecoration and reorganization, has devoured so many of our senses of self. Does a clean bathroom reflect your soul more authentically than the person you are with and for others? Then why are we allowing it to cannibalize so much of our time?

Yes, we should socialize boys and men to understand the domestic sphere as their responsibility. But I don’t think teaching them to fetishize cleanliness or multi-tasking is the solution. I also don’t think amassing enough capital to pay a woman to maintain that level of cleanliness is a long-term solution, either. What if we endeavored to care less? What if, instead of stomping around the house all Sunday cleaning the backsplash for house guests, I did things I actually wanted to do instead — and was happier when those house guests arrived?

“I’m having the realization,” one mom told me, “that of my five close friends with kids, the stay-at-home Dad has the messiest house. I love him and know he does so much cleaning, but I do wonder if he doesn’t have as much gender baggage about what it means to have a clean house. Honestly, it’s been freeing to experience — everyone is happy and healthy — and I feel like it reset my baseline and gave me permission for my own house.”

If you feel bound by these expectations: what would it take to free you? Because when I survey the hundreds of responses that arrived in my DMS when I posted the stats above, what I felt most was fatigue. Just look in the fucking drawer, is that where the bras go??? one woman wrote. God I’m so tired.

There’s also so much anger, and so much resentment. He knows his mom won’t judge him for the state of our house, so he doesn’t clean it. Wooooo boy do I get it. But what if, in my big age, I decide: she can judge me, but I won’t feel judged by it? What if I model to my friends that I don’t care about the state of their homes, either, I just care that I get to hang out with them? What if I prioritized what I want to do over what I had convinced myself others want me to do to my home that they’ll probably never see?

I did a version of this over the summer, as I allocated more and more of my non-Culture Study hours to growing 564 dahlias with my best friend here on the island. I cleaned my bathroom once in six weeks. I didn’t scrub the shower door — like, at all. When I saw a ring around the toilet bowl I went after it for ten seconds and called it good. I let the gunk from that time when the rice boiled over just hang out on the stovetop. I vacuumed when I got grossed out by the amount of dog hair and so did my partner. But maintaining the house was dead last on my list of priorities.

I periodically found myself apologizing to no one in particular: sorry it’s so dirty. But my partner didn’t care. No one did — or, more accurately, I cared, and then I stopped caring, and then no one cared.

What if I begin to understand that clean culture — like diet culture, like purity culture, like bourgeois parenting culture — persists in part because it conveniently keeps women so busy, fatigued, and distracted that they can’t more effectively combat patriarchy? What if I really internalized how much it’s used to make other people who can’t or won’t aspire to its ideals feel like shit? What if I understood that so much of the ideal of clean culture is achievable only for those with the means to outsource that labor, generally to underpaid women of color? What if I care less about shit that doesn’t matter?

What if I let go of the idea, as my friend Raena Boston of The Working Momtras put it, that “doing it all” is the same as “having it all”?

To be clear: I’m writing this for myself as much as I’m writing it for any of you. I’m also not talking about never washing your towels (which my brother definitely did not do for an entire summer when he was 20) or things that scream significant health hazard. Obviously this is something I’m still wrestling with — otherwise I wouldn’t find myself writing about it, in one veiled form or another, every six to nine months. But I keep circling back to it because it’s so insidious, and the smartest people I know still want to throw things because of it.

If feminism is, at least in part, the radical idea that women are people, then part of letting go of clean culture is the radical idea that women — and not just white, bourgeois women — deserve free time. More specifically: free time unburdened by the feeling that they “should” be cleaning or parenting or meal-prepping or doing laundry instead.

The GEPI report has many useful policy suggestions for how we can lessen the burdens of caregiving that suck up so much of women’s free time, and I endorse them all — including more paid use-or-lose-it paternity leave that men take on their own, which is one of the most reliable ways for men to become more equal partners when it comes to parenting. But policy and ideology go hand in hand, and lowering the bar requires both of them, working together.

I’m always suspicious of arguments that ask anyone who’s subjugated, in some way, to do more. But in this case, the work is difficult, particularly for bourgeois women, because the work feels like something we’re so rarely asked to do: less. ●

Further Reading:

Be sure to check out Virginia Sole-Smith and Sara Petersen’s Mini-Pod, The Cult of Perfect — and Claire Cain Miller’s article “The Relentlessness of Modern Parenting,” which was published in 2018 and CONNECTED SO MANY DOTS for me. Finally, I should mention the parenting chapter of Can’t Even: How Millennials Became the Burnout Generation — the interviews and research for that chapter continue to structure my thinking about the exhaustion of so much of millennial life.

Also: my publishing schedule (twice a week, every week!) means that sometimes I’m writing the Wednesday piece all day Tuesday, and tinkering with it well into the evening afterwards…which also makes it difficult to catch every typo. I always correct them (thanks Mom!!!) but I’m grateful for your understanding and tolerance.

How to break free of that cleanliness-defines-my-worth mindset? I don't think I am in that trap, and it is a combination of being AuDHD and simply not being able to; living alone for over a decade; and my grandmother's funeral.

At my grandmother's funeral, literally every single speaker talked about how much she loved her...house. How much care she put into it, how it was the joy of her life and source of her identity. When I was a kid, there was "clean" and there was "grandma clean". And after my mother died and I was rocked by grief, my grandmother attempted to console me by suggesting it wasn't that big of a loss because my mom (her daughter-in-law) wasn't a good housekeeper. (My mom was working full time, had four kids at home, and was literally dying.) I was so angry with my grandmother I barely every spoke to her again, and then at her funeral listening to everyone talk about her love of her house (!!) drove home what a waste of a life that was. She could have been kind. She could have been kind to my mom, who'd lost her own mother and was struggling. She could have been kind to me, her grand-daughter who was grieving. She could have had a life that meant something, but instead she focused on her house, which she saw as an extension of herself, and serviced her own pride and vanity. What a WASTE.

People get the exact amount of vote in my life choices that they experience the consequences. If someone who doesn't live in my house doesn't like the state of it, they can set up visits elsewhere or they can contribute to paying a housecleaning service. That's it. Only give people power when they also have the responsibility.

This is not exactly what you are talking about, but in our household, what I feel like I struggle most with allocating is admin work! My (male) partner does a lot of cooking and cleaning (and is frankly more bothered by mess than I am). But I feel like I am constantly drowning in a sea of paperwork/phone calls/emails - fighting with our health and dental insurance, calling contractors/plumbers/etc to do things for our house, filling out new tax paperwork. Not to mention fielding the barrage of spam emails/calls. I feel like this kind of stuff has expanded exponentially and I can’t tell if it’s just me, but it feels like every single one of these is a fight - someone sent the wrong paperwork to us, so I have to fill it out again; the insurance company makes a mistake on the claim and I have to file an appeal and follow up on it; contractor says they’re going to do something, doesn’t do it completely, and I have to fight to get them to come finish the job they agreed to. I get that we are all stretched so thin & distracted, but I am exhausted by trying to keep up with the apparently “essential” stuff of modern American adulthood 😅