Did you miss the announcement about THE CULTURE STUDY PODCAST?!?! The first episode comes out *this Wednesday* and it’s all about “why are clothes like this now,” featuring the great Amanda Mull.

Click here to get notifications for future episodes — or to become a paid subscriber, which comes with all sorts of perks. (If you’re already a paid subscriber here, it’s also 40% off — here’s the promo code). Your subscriptions truly do make this podcast possible (we’re playing around with ads, but the type of ads we’re doing do not even come close to covering Melody’s work).

We’ve already taped future episodes on Paw Patrol, personal coaching, F1, “contagious” divorce, and infrastructure (yes, for all of you who asked, my cohost is the amazing Deb Chachra!) but still need your questions about Kevin Bacon’s (very hot) Instagram, cold plunging, the Mean Girls reboot, weird celebrity philanthropies, and the resurgence of early 2000s music. Click here to ask.

AND WE HAVE A TRANS SANTA UPDATE! We have raised a truly staggering $16,513 to fulfill Trans Santa wishlists.

I have to fulfill one big request a day in order to avoid getting flagged for fraud by Amazon (ask me how I know this) but thus far we’ve been able to buy an E-Bike, a guitar, a Playstation + games, a full bedroom set, several Kindles, and a really nice cane. There’ll be much, much more to come — and I’ll share all of the cashout receipts from Venmo and eBay for transparency — but I’m so thrilled we’ll be able to make some trans youth feel cared for this season.

When I first started using makeup, eyeliner was the most intimidating implement of all. This was back in the mid-’90s, and the options available to me at the drugstore (and one “special” trip to the Clinique counter at The Bon Marche with my mom) were limited. Either I was up for drawing ON THE TIP OF MY EYELID with a black pencil or I wasn’t. Lip liner, that I could handle (bless you Wet n Wild in the brownish pink + lip gloss, a staple of 8th grade) but the one time I tried eyeliner as a teen I looked in the mirror and didn’t recognize myself.

I didn’t understand then that that feeling — that was the point. By transforming the visibility of the eye, eyeliner transforms the face. Today, I don’t think of my eyeliner face as not my face, I just think of them as two different faces, with two different approaches to the world. I like them both. But I needed some time and space to understand as much (and to learn how to apply gel eyeliner from its little pot, which has been my go-to for the last decade).

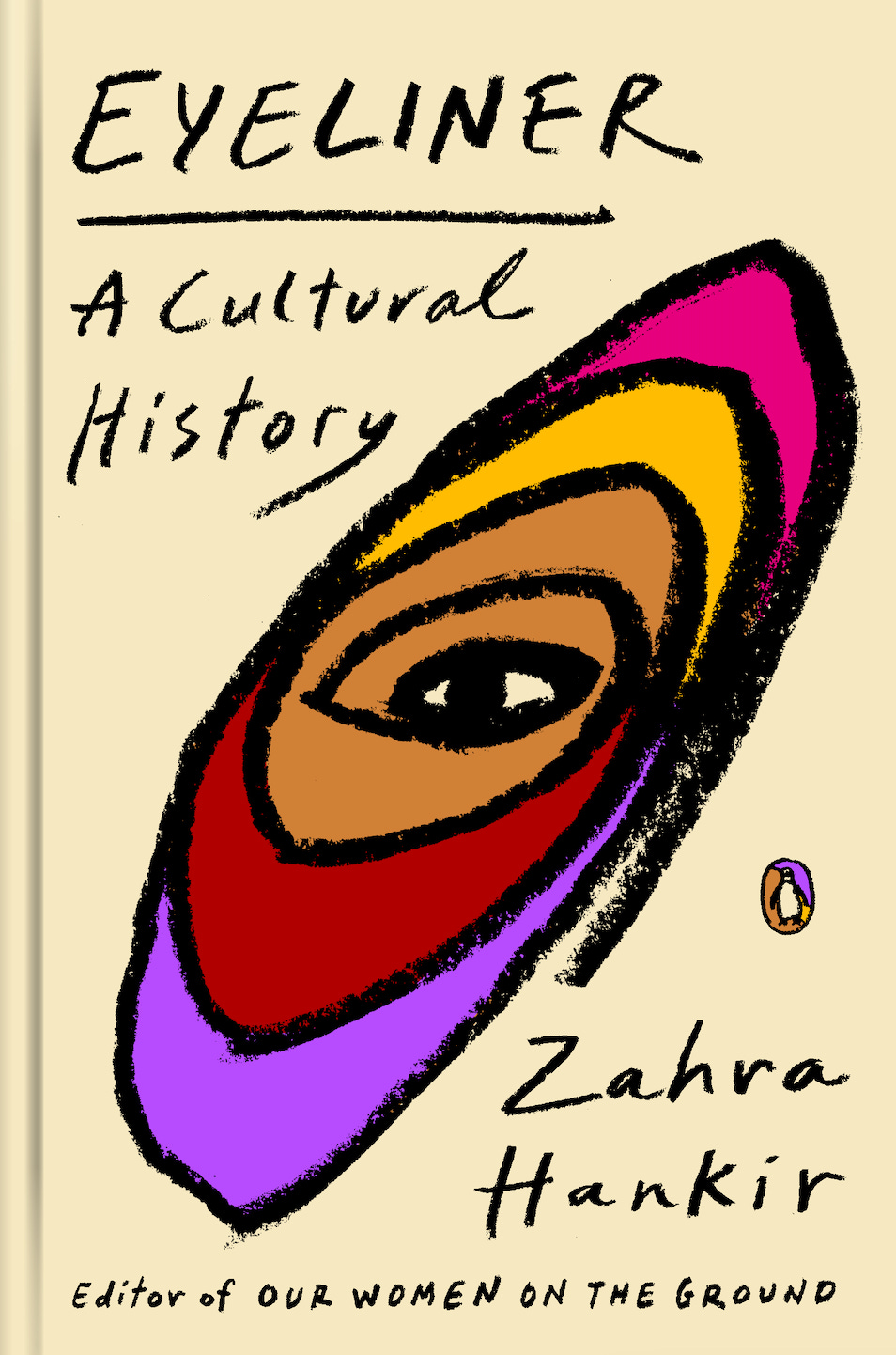

Zahra Hankir’s new book is all about the glories of eyeliner — and not just as a cosmetic, but as a cultural practice. She goes back in time, around the globe and into her own past, painting a picture that not only resituates eyeliner in the cultural imaginary but celebrates the myriad contributions of communities of color to beauty history. It’s a marvel — and regardless of your own history with make-up, I hope you’ll read on with an open and eager mind.

You can follow Zahra Hankir on Instagram here, find her website here, and buy Eyeliner: A Cultural History here.

There's a description of your mother from the intro that's really stuck with me: "I often watched her when she applied her makeup, which she did ritualistically, with great care and consideration, as if it weren't merely a beautification process but a moment of transcendence." As a way of making our way towards the themes of the book, what opens up — for analysis, for appreciation — when you approach makeup as an act of transcendence and ritual?

There's no shortage of what opens up when it comes to eyeliner – it's a portal to so many communities, cultures, and characters, from Afghanistan to Germany and Cleopatra to Adele. Such is its power. Eyeliner plays a significant role in expressing not only personal aesthetics but also cultural identity. The ritualistic application of lines to one's eyes can be a form of self-discovery. It allows wearers to connect with their ancestors and express facets of their identity that may be marginalized or hidden.

Eyeliner also becomes a powerful tool for women and people of all genders to reclaim, discover, or celebrate their femininity (however one defines femininity). The act of adorning oneself with eyeliner can be empowering, providing a sense of control over one's image and how we are perceived — this is especially true for members of the queer community.

The precise application of eyeliner can also carry symbolic weight that mirrors personal evolution and growth. Consider Amy Winehouse and her wings: they grew more prominent as her fame increased. And as she struggled with her confidence, especially as it pertained to her physical appearance, her flicks seemed almost to become a form of armor for her (along with her beehive). The absence of her wings seemed to say more than their presence.

Eyeliner also suggests an intimate connection with one's self. Its application can be a form of self-care and self-preservation, providing people with a moment for mindfulness and self-reflection. I experienced this during the lockdowns of the pandemic. There was really no obvious reason to make my eyes up; I was otherwise in sweats, like most, trying to navigate this new and terrifying reality. But I found that wearing eyeliner lent me a sense of agency or control during a frightening, unprecedented time. There wasn't a day that went by when I wasn't wearing it, even when I didn't see a single soul but myself in the mirror.

I also had some fun with it, experimenting with different looks. The precision and creativity in applying eyeliner elevate it from a mundane routine to an art form, allowing individuals to express their creativity on their canvas – the face. The hands must be steady; we stencil our eyes like a calligrapher might take a fountain pen to paper; we make a silent prayer to the beauty gods.

I also note in the book that eyeliner is very much about community and shared experiences. It's especially about the relationship between mothers and daughters. Applying eyeliner can be communal, an experience shared among friends and family, or within larger communities. I experienced this as a teenager, especially when applying it in dimly lit bathrooms in seedy Beirut nightclubs with my girlfriends, for example, or when learning how to master my wings with the help of my sister. I witnessed the shared nature of eyeliner application more recently among geisha in teahouses in Japan and kathakali dancers backstage in Kerala. There was a collective sense of identity and celebration in both spaces.

In some communities, especially in the global south, the ritualistic nature of eyeliner application has to do with the central role it plays in their daily lives: they may be wearing eyeliner to honor the gods, to protect themselves from the evil eye, to profess their religiosity, to treat their eyes medicinally, or to celebrate their heritage.

Bottom line: eyeliner as an act of ritual opens us up to a layered exploration of themes related to identity, empowerment, symbolism, self-care, artistic expression, and community. It encourages a deeper understanding of this pigment's profound impact on an individual's sense of self and connection to the broader world. Like ink, eyeliner delivers so many messages, so applying it with education, awareness and intentionality (and even a little prayer to the beauty gods) is crucial – at least to my mind!

You talk about how wearing eyeliner for the first time made it feel like your face had come into focus — and, in the years to come, allows you to feel more you, more deeply in touch with your identity.

If someone has never worn eyeliner — or maybe doesn't know how to perceive its presence on others — it's difficult to understand this process….how it does something to the face that no other type of makeup does.

Can you talk a little about the very basics of what it does to the eye and, by extension, the whole look of the face? [I love the point one of the teen girls quoted in the book makes about how it's not about covering anything up, it's about emboldening…or the point that R.O. Kwon makes in her essay about her own black under-eyeshadow, that it says to others: don't fuck with me)

Although eyeliner applications have varied over the centuries, cross-culturally, the aesthetic goal has always been the same: to beautify, enhance, enlarge, or change the shape of the eye. The cosmetic can transform faces from exhausted to awake, take an outfit from work-appropriate to date-appropriate, and elevate an overall look from bare and subdued to adorned and seductive — all with a few swipes.

The thickness of the lines can convey different messages, as can the angles of the wings: consider, for example, a thin line along the lid without a wing: this style imparts an office-ready sleek look that says "put together."

Now consider that same line extending towards the edges of the eyebrows, creating an elongated flick. That same line now says "confident and alluring," I’m ready for a date — it adds a touch of drama and flair, serving as a bold proclamation of individuality. Thicken that very same line even more, and you're now communicating a sense of empowerment and a flirtation with one's adventurous side.

Either way, when adorned with pigment, the eyes become a focal point of charisma and self-assurance. In that sense, eyeliner transcends mere grooming; it becomes a celebration of personal style.

The point here is that eyeliner is hugely personal. It can convey so many different facets of our identities to the world. It's really up to us what messages we'd like to share: we are confident, we belong to a proud subculture, we express ourselves, we are our own creations. There's an eyeliner style and a story for virtually every look. (As an aside, I'm such a fan of Kwon's aesthetic!)

The book is such an effective synthesis of history, analysis, and personal essay — but as someone who's tried to do a similar synthesis myself, I know how many layers of drafts and edits and reconceptualization probably went into this. We're process nerds here, so we'd love to hear as much detail as you're willing to share about the research and organizational process.

As a process nerd myself, I love this question so much! Because this was travel-driven, I had to arrange my research around my trips. Given that I wrote the book during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, I also had to be open to last-minute changes and developments (such as contracting COVID myself while I was in India). I devoted about two and a half months of research to each chapter and worked my way from chapter to chapter, ensuring full focus on each locale.

During those weeks, I spent all the time that I could immersing myself in each subject and each character: I watched movies and TV shows; I read books; I listened to interviews and podcasts; and as this is a very visual book, I also spent a lot of time looking at art and going to museums. I conducted this research before my travels to prepare myself for what I would witness.

Once I found myself on the ground in each respective country, I immersed myself in local traditions, communities, and practices — all of the things that I needed to do to feel like I could grasp the characters I was writing about. I have to say I treated each country and culture with the utmost sensitivity: I often speak of the Western gaze, but I'm very much aware of my own gaze (what I like to call the Arab gaze).

I must mention as well that given these were cultures that I was not from (or intimately familiar with), I did get some assistance from local researchers who helped me translate conversations with my characters, as well as texts that I could not otherwise access, so I am particularly indebted to them.

Working through each chapter slowly and giving myself ample time with each character helped me bring the academic research to life. I wanted this to be a character-focused book because, really, what is eyeliner if it is not about the people who have worn it historically and continue to wear it today, and why they choose to wear it?

Lastly, I hired an incredible fact-checker to work with me on this book, given it was heavily laden with facts! I recommend every writer do this if they can (it can admittedly be costly). It uplevels the quality of the work, and when you're so close to facts and text, it's sometimes impossible to catch glaring errors without a trained and sharp eye.

The very old school white second wave feminist argument about makeup was/is that it is a form of commodification-driven postfeminism: hollow liberation through lipstick, etc. etc. There are so many examples in your book that really challenge that understanding, situating eyeliner within a much broader, intersectional understanding of power, but I'd love to hear a few that stick out to you, or that give you particular pleasure to talk about when someone attempts to wield that argument.

My main rebuttal here is that eyeliner isn't just "makeup" or a "beauty product" that serves a purely aesthetic purpose. To explore this idea, we need first to understand the cosmetic’s origins: its roots trace back to Ancient Egypt, where it served purposes ranging from honoring the gods and warding off the evil eye to protecting against the sun's glare and treating eye ailments. Ancient Egyptians derived kohl, eyeliner's earliest iteration, from natural substances, including galena or malachite; it was stored in elaborate pots, moistened with liquid, and applied with an applicator. Men and women of all classes wore kohl; beautification was treated as an art and a spiritual or healing experience and was closely associated with rebirth. In hieroglyphs, the root of the term makeup artist means “to write” or “ engrave,” while the root of makeup palette means “to protect.”

Fast forward centuries, across the global south today, eyeliner is used in myriad ways, reminiscent of Ancient Egypt. In Petra, Jordan, Bedouin men wear kohl to shield their vision from the relentless sun and to express their religiosity, given the Prophet Muhammad was said to have worn a form of eyeliner. But kohl also serves as a symbol of cultural identity and pride, allowing the community to preserve the traditions of their ancestors.

The Wodaabe of Chad, a subset of the Fulani ethnic group, uses kohl partly to help attract potential partners during the Worso beauty contest, where the women judge the men. But beauty is not skin deep there; it is part of their moral code. In India, kajal is tied to the divine; children and adults wear it as a protective talisman. Meanwhile, Mexican-American Cholas and Chicanas use eyeliner to assert their aesthetic identities in the face of marginalization. In Iran, women have worn eyeliner as a way to resist the restrictions that are imposed upon them by the morality police.

In Japan, exploring the meticulous artistry of the geisha community’s makeup, we see how eyeliner — far from perpetuating a hollow notion of liberation — becomes a form of artistic expression, storytelling, and cultural preservation. The eyeliner geisha have worn around their eyes has roots in Ancient Japan, where it was believed that red makeup guarded against evil spirits.

Taken together, these global examples underscore that eyeliner is not just a cosmetic but a powerful symbol. Whether worn for religious reverence, cultural pride, or to assert identity in the face of adversity, eyeliner emerges as a nuanced and dynamic medium through which individuals navigate and negotiate their relationship with power, tradition, and self-expression. The varied uses of eyeliner across different cultures and communities challenge the one-size-fits-all critique, emphasizing the need for an intersectional understanding that respects the diverse ways individuals engage with this ancient and meaningful cosmetic practice.

I would hope that after reading my book, wearers of eyeliner (and those who encounter wearers of eyeliner) will recall that there is more to eyeliner than meets the eye: this seemingly frivolous object holds the weight of centuries of history, of empires, queens and kings, poets and writers, tribespeople and nomads.

I found the story of Anya Kneez deeply moving. As a way of closing, can you share some Anya's creation story and eyeliner's role within it?

Anya Kneez, yes, meaning "on your knees" – such an excellent title for a drag queen – is a Brooklyn-based Lebanese-American drag queen whose story I found to be quite profound and meaningful. Eyeliner played a significant role in Anya's journey of self-expression and empowerment, and beyond that, finding a space that worked for them in the queer community.

The love Charlie (as Anya is known when out of costume) has for eyeliner dates back to his childhood, when he experimented with makeup secretly. Raised by culturally conservative Lebanese parents in the US, Charlie found solace through makeup, fashion, and drag. In a 2022 Instagram post marking his birthday, he shared a photo of his younger self cutting his birthday cake in which he'd failed miserably at applying the cosmetic, missing his lower lash line completely.

"From the shitty eyeliner that I probably drew on with a marker, to the 'I'm a girl' t‑ shirt (that I secretly wish I still had)," he wrote, "I didn't even know what drag was at the time, but I was subconsciously doing it . . . It's funny how our childhood memories will return to remind us that our lives today make total sense."

That anecdote encapsulates Charlie and Anya's eyeliner journey. eyeliner is a magical tool, marking the moment Charlie transforms into Anya. For Charlie, applying eyeliner and lashes is the culmination of Anya's creation, signaling that she has come to life. This process allows Charlie to seamlessly transition between different aspects of his identity, embracing both his Arab heritage and his queer identity.

The act of applying eyeliner becomes a portal for Charlie to explore alternative lifestyles and express his gender and sexuality freely. Charlie draws inspiration from Lebanese divas like Haifa Wehbe and Nawal al-Zoghbi throughout his journey, incorporating their aesthetics into Anya's drag persona (I was a fan of both growing up so I particularly appreciated this detail).

Anya's story, which is closely intertwined with the role of eyeliner, exemplifies the power of drag as a form of self-discovery, expression, and advocacy for marginalized communities, bridging cultural gaps and fostering acceptance. As he says at one point, he feels naked without his eyeliner. To that, I (and so many others around the world) can relate. ●

You can follow Zahra Hankir on Instagram here, find her website here, and buy Eyeliner: A Cultural History here.

From the Culture Study Archive:

I personally experience the pressure in US culture for women to wear makeup as oppressive and hateful, but it’s nice to be reminded that makeup can mean completely different things to people in other cultures. The world is big and human experience is vast and varied!

Such serendipitous timing on this interview. Though im relatively adventurous with makeup, I'm a white woman with light eyes, and I've always shied away from black eyeliner because it just felt too bold. I would do a smudged-out charcoal gray, or a purple, but never black. Last night I went out with a BLACK winged eyeliner. It looked good, but I was soooo fraught because it did look and feel different so much a choice of, hey...I am going for it! It felt...like a brave step, but for such a silly reason. Anyway, it was nice to see this thing I was feeling validated and put into a larger cultural and historical context.