No Seriously, What is Intelligence?

And are IQ tests a load of crap? (Spoiler: yes)

I don’t mean to brag, but I get a lot of emails about books. There are far worse things to get emails about: back when I worked at BuzzFeed, I got a whole lot of emails about B-list celebrities “spotted” wearing a C-level fashion brand item. I get a lot of emails about books because there are an ever-dwindling number of places where authors can really get into the meat of a book for longer than a few sentences (or promote a book without a solid “hook” into the current newscycle).

But you, as Culture Study readers, have evidenced that 1) you’re up for long, detailed, meandering answers about a given subject matter and 2) you also like to buy books. I can’t tell you how much that rules, and how grateful I am for an audience this curious and engaged. But back to the book emails: sometimes, I’ll get an email about a book that absolutely lines up with my very legible obsessions (this is what happened with Kate Mangino’s Equal Partners: Improving Gender Equality at Home, and with Angela Garbes’ Essential Labor).

For both of those, my reply was immediate: yes, yes, let’s do this, absolutely. But sometimes I’ll open an email, read the description of a book, and think: this doesn’t catch my immediate curiosity. But maybe if I read more, if I get into messiness and oddities and history of it, I’ll realize that I’m actually really interested in something I didn’t realize I found interesting at all. Usually, the thing that makes that happen is the skill of the author — as a researcher, absolutely, but also as a writer who make concepts outside of my particular areas of expertise at once understandable and irresistible. See: Kristen Richardson’s The Season (Q&A here), Sandra Fox’s Jews of Summer (Q&A here), and Dan Bouk on census data (Q&A here).

The same holds true for Rina Bliss’s Rethinking Intelligence — if only because I don’t think I had thought enough about how we currently think of intelligence to consider how it could be re-thought. I know that standardized testing is bullshit, as I know many of you do — that it’s fundamentally a test of how well you know how to take a test, not of intelligence itself. But Bliss, a professor at Rutgers whose research focuses on the sociology of race and genomics, asks us to reconsider a whole lot more than that — particularly when it comes to both the past and future of the very idea of intelligence. (She also explains the popularity of Mensa at a very certain moment in history, which I’ve wanted to understand for years).

Maybe this is very obviously your thing. Maybe you hadn’t considered it being your thing. But who would we be if only pursued knowledge about things we already knew held our interest? There’s a lot of ways you could describe that sort of person. Including: not very interesting themselves.

You can find Rina Bliss’s website here, and you can pre-order Rethinking Intelligence — which comes out April 11th! — here.

You talk about this quite evocatively in the book, but I’d love readers to get a sense of the story of how you developed your interest in intelligence — I found it pretty fascinating and layered (and also know that a lot of people will be familiar with using others’ perception of intelligence as a means of blunting the blow of always being “different” in some way).

Being intelligent was my mantra. I believed it was my ticket out.

I grew up in a middle-class home in a middle-of-the-road neighborhood in Los Angeles’s San Fernando Valley. Our public schools provided a mediocre education to an average sample of LA youth (which was remarkably diverse, thanks to busing laws that helped to redistribute the city’s population). At first glance, there was nothing noteworthy nor problematic about my situation. But prick the surface and a different image appears.

My family was struggling. My mom, Liza (n.e Guojia Hua Caryabudi), hailed from the floating city of Banjarmasin in Indonesia. Distant relatives had snatched her from her young laboring parents and planted her in a Dutch convent on the neighboring island of Java. In college, she joined a generation of Western-enculturated Indonesians who shipped off to Europe and the United States to study abroad. When her scholarship ran out, she took up work as a domestic servant in the Hollywood Hills. She vowed to do anything to remain.

My dad, Nathaniel Jr. (also known as “Junior” or “Natty”), belonged to one of the well-to-do families that lived in those Hills, a prominent military family in California politics. But beneath a veneer of Democratic respectability lay a family ravaged by trauma, abuse, and addiction. Tormented by prisoner-of- war flashbacks, my grandfather terrorized my father with knockout blows and fugues of rage. By eight, my dad was regularly robbing his parents’ medicine cabinet of sleeping pills and painkillers. By eighteen, he was subsisting on a daily diet of codeine and barbiturates.

My mom and dad met one balmy day in 1972, as they were descending the hills for the valley below. They flirted at the bus stop at Hollywood and Vine and then boldly arranged to meet again. It was love at first sight.

Lifted by love, my parents tried to make a fresh start. My mom took a secretarial course and my dad started law school. They rented a sunny apartment in Sherman Oaks. Yet by the time I came around, substance abuse had overtaken my dad, and it had moved him to the streets, to the slippery recesses of junk dens and crack houses. As he spiraled, my mom ferried us to a safer place. She got an office job in Beverly Hills, rented a new apartment just for the two of us, and found someone to watch me day and night as she hustled overtime to support us.

It was hard waking up to my mom leaving every morning and heartbreaking to fall asleep before she got home. My dad would come over to play with me and the other little ones under the care of our building’s sitter, but he was always on the brink of an overdose and often unintelligible.

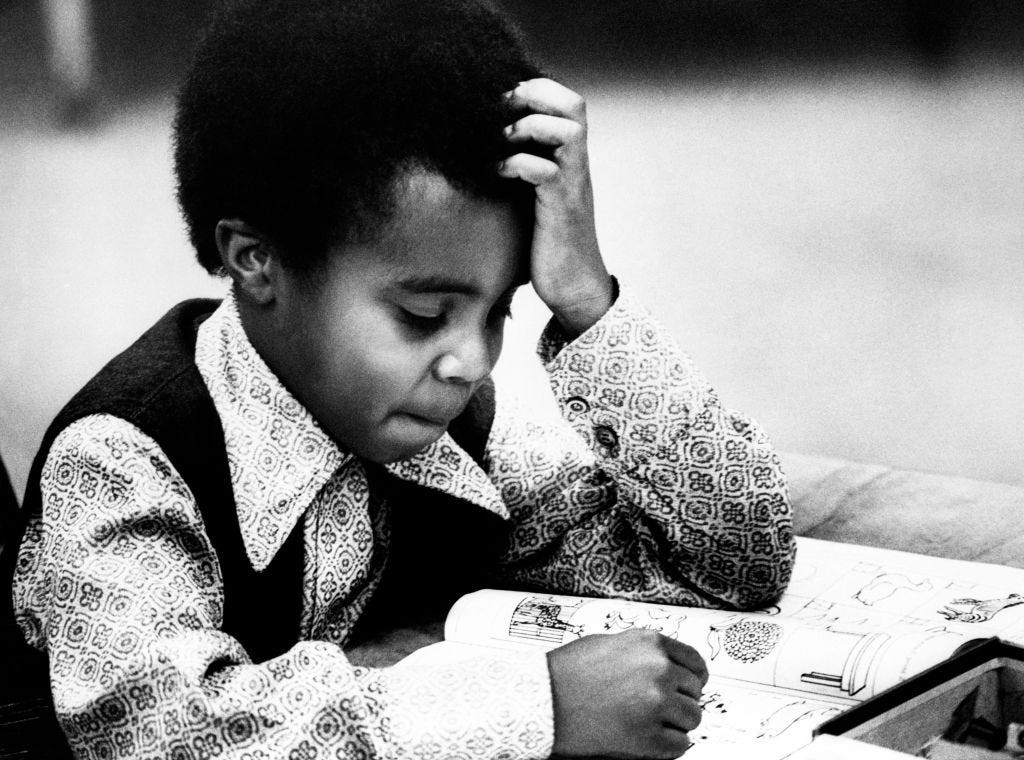

Shockingly, however, my real troubles began when I started school. As the only Southeast Asian biracial kid in my classes, I was immediately regarded as an oddball—not white, not black, not even yellow . . . an indeterminate tawny “other.” One boy in my kindergarten class made a game of rounding up a group of kids to chase me around the playground, making squint-eyed faces and hurling epithets at me. Another kid at my summer program would cut me off when I spoke, to deliver slurs and threats. Negative stereotypes abounded and crowded the air I breathed every day.

The one positive about those stereotypes: kids thought I was smart. Being Asian (even just part) seemed to magically confer upon me a superior intellect. As one school year gave way to another, I took solace in my perceived giftedness. Believing there was no other way to go, I read, I studied, I achieved, and I outsmarted.

Or so I thought.

The way I saw intelligence as a kid was limited, to say the least. I believed being smart was an innate quality, and this is exactly how grown-ups around me talked about it. In the classroom, I heard the word gifted just about every time anyone talked about intelligence. My teachers and TAs encouraged only some of us students to dream of being intellectuals and growing up to use our smarts. Others they would applaud for their athletic ability, as if being intelligent and physically adept were opposing things. In the media, scientists were intelligent. Doctors were intelligent. Professors were intelligent. Engineers, too. In my eyes, these high achievers were winning at life as a result of their God-given talents, with little exertion required from them.

My understanding of it was you were either born with intelligence, or not. It certainly wasn’t something that anyone could learn and develop as a skill over time.

Growing up with American media, the stereotypes I saw in TV and movies certainly didn’t help with this misconception: between the “autistic-coded math genius” and the “East Asian tech wiz,” brainy, intelligent characters were either white men (and the main character) or people of color (in a supporting role).

Popular science only made matters worse. For centuries, evolutionary biology, genetics, phrenology, and psychology popularized the idea that, like height and weight distribution, intelligence ran in families. It was etched into our DNA, a part of our innate biology. Scientists had worked hard to perfect intelligence measurement. A simple IQ test said it all and foretold our future.

Let’s start broad: what is our common understanding of intelligence, and how does it connect to patriarchal and white supremacist ideologies? I’m interested in parsing the “heritable” component of it all, but I’d also love to hear more about the fascination with measuring and ranking it through the IQ test — how is that obsession itself an outgrowth of how we conceive of intelligence’s source and character?

The common understanding is that our intelligence is what makes us human. We are the only species with the ability to form elaborate sentences, do mathematical equations, and explicitly create art. And yet common understanding is also that we are not all the same—we have different IQs and different genetics, and some of us rank high on intelligence scales while others rank low.

For centuries science told us some version of this—that intelligence was something we were born with, that it was an intrinsic and unchanging part of our human individuality, that it came to us from our parents and ancestors, and that it determined what kind of life we would have, and in a sense, what kind of life we deserved. Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, they all believed this. Plato, for one, said that those born highly intelligent were the only people fit to lead. He also said that those of low intelligence should be subjugated and never allowed to procreate with people of higher intelligence.

Later, when colonialism and the slave trade got going, the naturalists, philosophers, and proto-scientists of the day tacked on a racial and sexual valence to the meaning of intelligence. Scholars like David Hume and Immanuel Kant claimed that only White males could be highly intelligent. With such a tenacious and persisting dogma, it’s no wonder that Charles Darwin also believed intelligence was passed on through our genes, and that only certain families of certain races possessed intelligence. There has been little attention paid to this part of his theory of evolution, and yet it was so essential to it.

The person to whom we attribute the “ugly” genetic theories is another scientist of Darwin’s time, his own cousin Francis Galton. Galton was actually venerated — he was knighted for his work — and him who established the field of genetics with a focus on intelligence measurement and ranking. He set up shop at one end of Hyde Park, in London, and formulated the first rank-comparison system mapping human intelligence onto a bell curve. IQ tests were invented some years later, and they took hold around Europe and the U.S., culminating in a round of national Eugenics (“better breeding”) movements and Naziism.

Though most contemporary governments now champion equality of all humans, and though scientists now criticize Eugenics with our better understanding of our genomes, we still use IQ tests and other spin-off standardized tests today, especially in public education. IQ tests are used throughout the global economy in hiring, job placement, and promotion, and they are used to track students for gifted or special education programs in an array of public and private education systems. We haven’t yet had a true reckoning with this legacy or the inadequacy of the tests themselves.

Please indulge this slight tangent to the question above: Can you break down the interest in Mensa? Why did it become popular when it did, why does that popularity endure amongst a certain generation? I feel like most people now understand bragging about a Mensa membership as somehow in poor taste….but maybe we’re doing the same thing now when it comes to the fetishization of a certain type of measurable intelligence, we’ve just cloaked it better?

Mensa, originally called “The High IQ Club,” is an organization founded by a couple of ultra-conservative London-based barristers that were pining after a disempowered aristocracy in the Postwar Period. They were big fans of IQ tests and the Galtonian notion of intellectual hierarchy. They set the bar at the Top Percentile of the IQ curve, which they later expanded to the top 2%.

With IQ testing, Mensa grew in popularity throughout the 20th century, particularly in the U.S. amongst the Boomer Generation. Like Eugenics, which didn’t actually go anywhere—it just transformed itself to a “race-free” science à la “anyone can be smart”—Mensa sold itself as a way for people to learn just how special they were. Parents like my mom, who invested everything in her daughter’s education, and wanted me to test high to get tracked for gifted schooling. She saw Mensa membership as a way to propel me forward in life, to access the American Dream. A lot of immigrants, single moms, parents of color, and working-poor caregivers have seen IQ as a rescue measure for their kids—and this has been reinforced structurally by the public education system.

I think the waning of using tests and Mensa membership as bragging rights comes from the popularization of another intelligence arena which is the notion of multiple intelligences. In the 1980s, when I was being tested and tracked, a Harvard psychologist, Howard Gardner, surprised the world with data proving that human intelligence is polyvalent. The kind of intelligence picked up by IQ tests is limited, and therefore we should be wary of IQ scores. IQ tests cannot tell us how intelligent we are.

Today, this idea — along with other contributions, such as Daniel Goleman’s theory of emotional intelligence — have become a countervailing pressure to all who would champion their so-called “high IQ.” There has also been an amazing boom in the neuroscience of brain plasticity. It turns out that our genes give us the ability to learn from our environments our whole lives. Our brains are always in process, growing and developing by learning from our surroundings. Our genetics make this process of intelligence possible.

Meanwhile, our mental and physical health can stop our genes from going to work as they should. Research into gene-expression, called “epigenetics,” shows us that our genomes fail to empower us when we live and learn in stultifying environments. In fact, stress—which is something most of us face no matter where we are or where we come from—is so harmful to our DNA that it can change it and make us less effective at using our intelligence.

Some of this knowledge is percolating in pop culture now. But so is the notion of a genetic IQ. And the IQ gene hunt continues on. Researchers are still using IQ scores to find genetic culprits for intelligence. And intelligence testing is still a big part of how we measure ability in education. So the dogma of the past 2000 years, and some underlying belief that we are only as good as our scores, will not likely fade away anytime soon.

What is the fundamental flaw in trying to extrapolate IQ from a genome, as so many DNA tests are attempting to do? And what do you think is really behind 1) the urge to market products this way, despite pretty shaky science but also 2) consumers’ desire to buy them? Like, do only people who already consider themselves intelligent take these tests???? Why would you do this to your child?!? [And how does the existence of these dubiously useful tests point to a much darker CRISPR technology future?]

There is a huge flaw in IQ tests, no matter which one you look at and when. It is a problem for standardized tests all around, but it is particularly detrimental in the case of IQ testing. I’m talking about privilege. IQ tests privilege test-takers that have been educated, or raised by educated caregivers, cultured with the same cultural references that are baked into the test questions, and trained to take tests, to perform well in a test-taking environment. IQ tests also privilege test-takers who have had adequate access to healthy foods, clean air and water, and safe and nurturing living environments. Scientists working in a number of fields—from education to psychology to data science—have shown that you can drive test scores up by giving a deprived kid these things. They have also shown that you can drive scores down by taking them away, and by priming test-takers with stereotypes and negative notions that make them feel like they are destined to fail. So the scores are inadequate and therefore saying that they are a true outer presentation of a person’s inner genetics is false. You can’t look for genes for something that isn’t even real.

Yet companies will try to make money off of popular misconceptions because, let’s face it, this is one of the most widespread and enduring lies that we humans have told ourselves. And it’s not just elitist moms and dads or Ivy League colleges that are invested in these tests. There are many caregivers of neurodiverse kids who are struggling to get society to recognize how uniquely intelligent their kids are. A high IQ score is presently one of the only ways to do just that.

The thing I worry about is how close we are to gene-editing our brains, and on a mass scale. Every day, we grow nearer to the launch of neuro-CRISPR markets [which sell the editing of genes]. These will be very important for people suffering from mental illness and cognitive dysfunction. But what will happen if we take all these genetic variants as true markers of our intelligence as defined by IQ? What will happen if we then start tweaking those variants in ourselves and our children, when they are in fact false positives? What kind of “off-target,” or unintended, effects might we see? I caution us from going down that road, especially when we have so much we can do as a society to equalize our social environments and improve our learning environments for all.

So if intelligence isn’t what we’ve been taught it is, what we commonly understand it is, what the IQ test tells us it is…..what is it? Within that understanding, how is it nurtured differently? And what are the stakes of us rethinking it?

Just as I recommend understanding our mind’s genetics in terms of cognition that is attuned to your environment, I recommend understanding intelligence in terms of awareness of that environment. Being alert to and contemplative of your environment is the most natural and important part of having a human brain and being alive. To rethink intelligence as awareness can help open up the world to you in terms of growth, mindfulness, connectivity, and collective creativity.

Awareness actually prevents us from thinking about amounts and scores. Rather, it inspires us to realize our inherent neuroplasticity — our continual growth and development. It helps us stay focused on cognition, cognitive health, and powering our brains to mobilize. It helps us move, seize, and grow, and to do so collaboratively in connection with those around us.

What we really need to do is think about the active processes our brains are engaged in and the quality of those processes. We need to shift toward intelligence as awareness born of our growth, mindfulness, and connectivity, and retool how we consider basic thought processes.

Most importantly, we need to examine our environments and ask ourselves how we can improve them. We must start seeing ourselves as intricately connected to the well-being of that environment and above all, the people within it.

Reimagining intelligence in terms of active, ongoing, limitless awareness has the potential to subvert many social arenas of our current system. Right now, intelligence scoring has us locked into a system of rewarding some and disadvantaging others. We mark a select few as gifted and others as ineducable, and we score people against one another, marking some as better and others as worse. Just imagine how different our lives could be without that hierarchy—especially if early childhood education and secondary education were to discontinue the practice of ranking. If we replaced scoring with growth mindset, mindfulness, and connected learning in a child’s earliest educational settings, we could offer that child not only the chance of an enriched education, but also an enriched sense of self-worth.

A new paradigm for intelligence can also empower the many of us who are so very far beyond those early years. Imagine having the ability to create a new relationship to your intelligence—one not based in competition or scarcity but rather one that stimulates growth and self-confidence. We can start by realizing that we are not inherently flawed, no matter how real our internalized fears are, and no matter how much the trauma of earlier events in life reverberates through our current life experiences. We are not the sum of our test scores.

All of us have come up under the score-based paradigm, so very few of us will have escaped the trauma that it has engendered. But we can begin healing, starting with ourselves and our own relationship to intelligence. We can reframe our “wins” and our “losses” as a false dichotomy, we can reject rank-comparison where we encounter it, and we can begin valuing ourselves (and all others) as the innately intelligent beings that we are. ●

You can pre-order Rethinking Intelligence — which comes out April 11th! — here.

So interesting. I can't even tell you how much I was harmed by the idea that "intelligent" was the most important thing one could be and that intelligence was some sort of raw material I was blessed with and duty-bound to refine and express.

One part of this topic I've been coming back to frequently recently is the idea of effective or functional intelligence (a term I invented, idk if there's a real or better one). But I've made significant progress dealing with my ADHD, depression, and anxiety in the past few years and I've had the startling sense that I'm MUCH smarter now.

Of course, I don't know more things than I used to (now that I'm outside the college life, I probably know less) but I feel smarter because I'm better able to manage my energy and distribute my work.

Like, I've always written. But only recently have I been able to consistently organize myself and finish actual pieces and then feel comfortable publishing them. Who's smarter, the me who maybe knew more and thought more complexly but who never published and never affected anyone? Or the me who actually articulates and affects people?

I don't even know how much I care either. I'd rather be effective than intelligent.

I remember those Mensa ads in some magazine or other my grandmother always had around the house when I was a kid.

Reading this, I'm thinking about the great section on the culture of "smart" in Karen Ho's Wall Street ethnography Liquidated, and how the idea of smartness has such power in certain circles, in this "we're so smart we don't need to actually be experts on anything" kind of way. I feel like you really, really see that in certain kinds of media figures (Nate Silver, Matt Yglesias, to a certain extent Emily Oster) whose belief in their own raw intelligence makes them think themselves qualified to comment on literally anything after only the most shallow investigation of what's going on -- and that they get taken seriously in doing that!