If you open this newsletter all the time, if you forward to your friends and co-workers, if it challenges you to think in new and different ways — consider subscribing.

You’ll get access to the weekly Things I Read and Loved at the end of the Sunday newsletter, the massive links/recs posts, the ability to comment, and the knowledge that you’re paying for the stuff that adds value to your life. Plus, there’s the threads: like this month’s What Are You Reading? (900+ comments, plus Melody’s romance syllabus) and What Are You *Not* Buying (On the Internet) which went in many, MANY unexpected (but useful!) directions.

Two people meet at some point in their 20s, fall in love, and for some reason — a job, a grad school opportunity, whatever — decide to move to a place where they know very few people. Maybe they make some friends immediately, but more likely: they don’t. Maybe they already have a kid, maybe they start trying to have one (or a second) shortly after they move. They’re relatively early in their careers and spending a lot of time trying to advance them, so have very little energy to allocate to cultivating friendships that aren’t ready-made, e.g., a school cohort or friends at work.

Those friendships are nice but somewhat shallow, in part because these people spend most of their spare time with their partner, or working, or parenting. It’s hard to get a sitter and you don’t feel super comfortable just lugging your kid to other people’s spaces. It’s not that you don’t get out of the house; it’s just that when you do, it’s usually with your partner and kids. Meanwhile, maybe a parent’s health is deteriorating and you’re struggling to navigate care for them across the country. Or maybe you moved closer to your parents to relieve your overwhelming childcare needs….but now you realize your parents are your primary points of adult contact.

One day you wake up and realize you’re deep in the friendship dip. You’re moderately stable in your job and housing. You’ve kinda figured out your partnership and/or parenting. You’re decently versed in local issues and a member of the neighborhood Facebook group and/or have exchanged numbers with a few neighbors or know the name of several dogs on your street. You have a lovely text threads with friends from your childhood or your 20s that pop off every few days.

But let’s be real: it’s just not enough. When you let yourself think about it, you feel incredibly isolated. Periodically the thought surfaces, unwanted and unbidden: I’ve been here [this many years] and still haven’t made a real friend.

I’ve felt this sort of quiet-frustration-bordering-on-desperation before. It’s at the heart of Friend Group, the book I’m currently researching and writing. Unlike the dozens of books that focus on how to make friends as an adult, I’m trying to take a larger step back and think about the structures we’ve created that make it so hard to follow those books’ (usually pretty decent) advice.

Some of the difficulty has to do with infrastructure: car culture makes it really hard to just hang out. Some of it has to do with mobility: more specifically, the way educated Americans are more likely to move away from the places where they have networks of support in pursuit of job and life opportunities. Some of it has to do with the way work has cannibalized our time and made “hanging out” seem like a failure of optimization.

But a whole lot of this ethos stems from a deep-seated belief in individualism. We think that just because we can “do it ourselves” (and by “it,” I mean raising kids, performing domestic labor, caring for others, finding economic security, living life) that we should do it ourselves….and our ability to do so evinces innate moral fortitude. We’re better people, in other words, because we did it alone.

You can read that and understand it as bullshit and simultaneously internalize and abide by that line of thinking. That’s the bitch of ideology. To start dismantling it, we have to learn to recognize its various shapes. Because this isn’t just about finding deep and meaningful friendship in your 30s and 40s, or even making parenting slightly less miserable, although both of those are noble and worthy causes. The myth of individualism is at the very heart of American inequality — social, racial, and financial. But to understand why, you have to go back: not to the founding of the country, as many assume, but to the presidency of Andrew Jackson.

That’s what political historian Alex Zakaras argues in his stunning (and accessible) book, The Roots of American Individualism: Political Myth in the Age of Jackson. I’m so accustomed to our current broken democratic system that I forget we used to have a differently broken one, with much more power consolidated around wealthy landowners. (To be fair, wealthy landowners still control our current system, we just pretend that “allowing” most people to vote negates it). Back in the late 18th century, these elites were terrified of the word democracy: they hated monarchy, but they also didn’t think the future of the country should be handed to the general (white, male) public.

The Jacksonian Democrats, by contrast, were Big Democracy Boosters — with significant limits. They believed all white male citizens should have power within the government. They thought judges should be elected not appointed (and elected every few years, to prevent corruption). They believed all white men, regardless of background, should have the right to flourish.

They also believed strongly in Manifest Destiny — the idea that white men have the right, the God-given destiny, to colonize what they understood as “uninhabited” (read: inhabited by Indigenous people) land, and that the capitalist economy should be allowed to figure itself out (survival of the fittest!) with very little intervention. Within this framework, slavery (at least in the South) was understood as a necessity to ensure the spread of white men’s financial opportunity.

Zakaras organizes this thinking into three separate but overlapping myths, each with its own protagonist: the independent proprietor (the small businessman, the small farmer, etc.); the rights-bearer (the man fleeing the constrictive tyranny of the ‘Old World’ to enjoy the freedoms of religion, expression, arms-bearing, etc., that define the ‘New World’); and the self-made man (who thrives through hard work in a society free of insurmountable class hierarchies).

These myths were present in the late 1700s, but they didn’t become as useful or prominent until the early 1800s when, Zakaras argues, they began to transform to accommodate a new generation of Americans who hadn’t lived through the Revolutionary War. They also collided with easy access to credit, the continued expansion of American territories, the arrival of new European immigrants, renewed religious (and specifically evangelical) fervor, physical and class mobility, and the need to continually refine the justification for both slavery and the ongoing displacement and genocide of Native peoples.

How do you weave all of those things together under the banner of liberty and democracy? How do you balance pledges of equality with the reality of slavery (and the lack of suffrage for women)? You need a BIG, COMPLICATED, ENDURING myth. A foundational myth — one that can both “make sense of political events and experiences,” as Zakaras puts it, and “construct a glorified image of a national people and present it as a worthy object of devotion and sacrifice,” recounting “a story of national origins that illustrates its people’s basic values or character traits.”

You need something that convinces Americans with access to power that the way they’re doing things is not just different, but undeniably superior. You need a myth like individualism.

In the early 1830s, Alexis de Tocqueville embarked from France to the United States, tasked with observing the prison system. He sorta did that, but mostly he just traveled around, observing a nation very much in flux — and deeply imbued with individualism.

As Tocqueville put it in Democracy in America, Book 2:

Individualism is a novel expression, to which a novel idea has given birth. Our fathers were only acquainted with egotism. Egotism is a passionate and exaggerated love of self, which leads a man to connect everything with his own person, and to prefer himself to everything in the world. Individualism is a mature and calm feeling, which disposes each member of the community to sever himself from the mass of his fellow-creatures; and to draw apart with his family and his friends; so that, after he has thus formed a little circle of his own, he willingly leaves society at large to itself. Egotism originates in blind instinct: individualism proceeds from erroneous judgment more than from depraved feelings; it originates as much in the deficiencies of the mind as in the perversity of the heart. Egotism blights the germ of all virtue; individualism, at first, only saps the virtues of public life; but, in the long run, it attacks and destroys all others, and is at length absorbed in downright egotism.

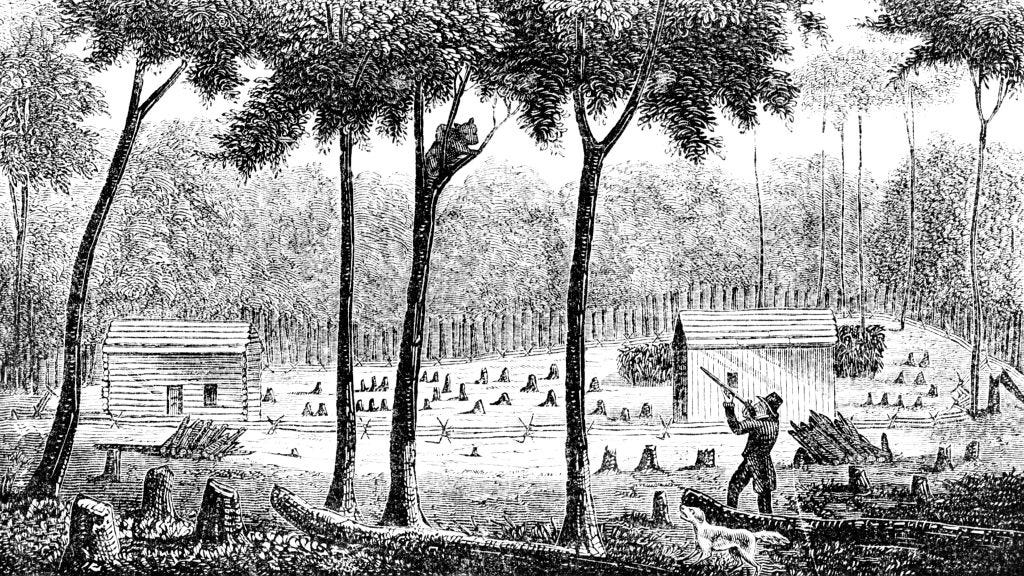

What Tocqueville describes is a pretty classically American me & mine philosophy: the state is useful in its ability to create conditions that facilitate your personal economic growth and stability (see: legalized slavery; the Homestead Act; the use of the American military to eradicate Native populations; the postal service to facilitate communication and commerce).

Once that growth and stability is achieved, you become disinterested (or outright hostile) when it comes to offering that sort of stability to others, particularly if they are of a class of people you believe inferior or as potentially infringing upon your liberty. (See: animosity toward so-called “government handouts” that primarily benefit women and people of color paired with outrage over cuts in programs that make their stability possible, like farm subsidies, incredibly low-cost grazing on federal lands, tax cuts on the rich, low estate taxes, mortgage deductions, the list goes on).

Tocqueville saw “free” public institutions — most notably roads and other forms of infrastructure — as a partial antidote to the worst effects of individualism. A road physically connects you to others; massive infrastructure projects that make life markedly smoother are only possible by pooling funds through the collection of taxes. It was, at least in theory, a form of ideological détente: let people have their freedoms and their dreams of autonomy, but keep them tethered to one another through shared need, which could also include things like military defense, access to clean water, libraries, public education, etc.

But what happens when those shared needs come to be understood as givens? When ongoing privatization allows the illusion of total autonomy to flourish? Well, you get a significant percentage of the current population of my home state of Idaho, amongst other places. We’ve reached what Tocqueville described: downright egotism. It’s the ideological wall I find impossible to scale: I don’t know how to make you care about other people.

The persistence of slavery had always challenged the ideals of Jacksonian Democracy. But by 1854, with the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act, the center simply could not hold. The act’s intention was straightforward: turn part of the Louisiana Purchase into official territories, thereby making them easier to settle — and easier for the Trans-Continental Railroad to, well, traverse. But creating those territories negated the Missouri Compromise, which had temporarily kept the warring factions of abolitionists and slave owners at bay. The new territories soon became free-for-alls for interests attempting to sway the eventual votes to legalize (or ban) slavery.

Historians have teased out much more complicated thoughts on this era, but I recognize it as one of those moments when white people had a well-worn story of why things had to be the way they were — and then, when it became clear that the story was indefensible, they just built the story into something bigger and bolder.

And so, in the years to come, they embroidered and retconned the specifics of the individualist myth to accommodate emerging realities and conflicts: the extent of the Native genocide, the place of non-white immigrants in the hierarchy, the deracialization of Irish and Italian immigrants, the horror of the Holocaust, the ongoing horror of lynchings, and the utterly nonsensical rationales at the heart of Trickle-Down Economics. (I could go on. For several paragraphs.)

For those weaving and receptive to this narrative, it did not matter how convoluted the story became (see especially: The Lost Cause of Confederacy; the persistence of the “savage” in Westerns; Holocaust denial; All Lives Matter). What mattered is you could still claim the overarching narrative as true — and thus preserve an understanding of self, of nation, of deservedness and superiority.

White men established their vision of the ideal American ethos — the urge towards self-determination, access to class mobility, the maxims of personal responsibility, exercising dominion over the land, even land ownership itself as a hallmark of success — when they were the only ones with access to it. Crucially, much of that access, particularly in the Jacksonian period, was predicated on stealing land from Indigenous people and the enslavement of Black Americans.

And yet, eventually, that “free” land ran out — or at least dwindled. Over the next century, the vote expanded to women and people of color, and so too did (theoretical) access to credit, to wealth, to power. But the white men already in power took others’ failure to achieve as evidence of a lack of will and grit — and proof they weren’t “real” Americans. It’s as if they started a game of Monopoly hours before everyone else, bought up everything save two properties, and then invited the rest of the people to join — and swiftly blamed and shamed them for losing.

Within this framework, new immigrants can only “become” American when they achieve like white men. Women’s lagging achievement rates when it comes to positions of power and wealth aren’t the result of deeply engrained wage gaps, sexist policy, lack of parental care leave, lack of childcare access, and the paltry value placed on care work — they’re just not cut out for success. The racial wealth gap isn’t related to the legacy of slavery and red-lining, it’s because Black people are lazy and overly dependent on government assistance.1

For such a well-polished myth, individualism (at least in this moment) feels clunky and ham-fisted. It’s so clearly at cross-purposes with what so many people crave! Articulate its tenets in conversation or debate and you come off like a total asshole! It’s at the heart of our most cruel and exacting policy stances, from the lack of mandatory paid parental leave to the handling of student loan debt. But it also animates incredibly banal shifts in the funding of public infrastructure, transportation, and the arts. It’s why so many of us still feel the need to do things on our own — or under the illusion that we’re doing them on our own. It makes it so easy to judge others according to that same logic.

Individualism is bullshit! And yet, it endures: in large part because it was built on the foundation of white supremacy — of white people having the most power and control. And as long as you believe that we live in a nation where opportunity is equally available to all, you can justify the racial wealth gap, the rates of incarceration, racial discrepancies in health care, and maternal mortality rates. The myth of individualism makes those utterly nonsensical stats make sense.

And here’s the hard part. You can’t just decide fuck individualism, I’m blowing it up. You have to replace it with a better, more equitable story of who we are as a country and how we organize our society. Which, for a lot of people, would mean giving up a modicum of power. Liberal white people can loathe the effects of individualism and still benefit enough from their placement within the racial hierarchy to not dismantle it altogether. Other people with more privilege in the established hierarchy (because of when or how they came to this country, because of their class status, because of their race) can dislike white supremacy in general but still benefit from the status quo it structures.

Millions of people — and white people in particular — would rather endure physical isolation, generalized loneliness, caregiving exhaustion, and financial precarity than relinquish some of their societal power. That’s a far less optimistic foundational myth than individualism. But it’s a far more honest one. ●

For those who live in the U.S.: How do you see individualism manifest in your world? How have you or your family rejected or quietly embraced its core ideologies? If you don’t live in the U.S., how does your nation think of individualism — and what other founding myths are at work instead or alongside?

Subscribing gives you access to the weekly discussion threads, which are so weirdly addictive, moving, and soothing. It’s also how you’ll get the Weekly Subscriber-Only Things I’ve Read and Loved Round-Up, including the Just Trust Me. Plus it’s a very simple way to show that you value the work that goes into creating this newsletter every week.

As always, if you are a contingent worker or un- or under-employed, just email and I’ll give you a free subscription, no questions asked. (I process these in chunks, so if you’ve emailed recently I promise it’ll come through soon). If you’d like to underwrite one of those subscriptions, you can donate one here.

If you’re reading this in your inbox, you can find a shareable version online here. You can follow me on Instagram here — and you can always reach me at annehelenpetersen@gmail.com.

I never use footnotes here but I couldn’t resist this one: Zakaras draws a line between the Jacksonian-era myth of class mobility and the reticence, particularly on the part of working-class whites, to engage in class solidarity. Unlike other countries where class status was more entrenched, white people internalized the idea that they should align themselves not with other members of the working class, doing different types of low-wage and often exploited work across the nation, but with the class they aspired to enter. Politicians both then and now exploited race-based prejudices and fears (then: miscegenation; now: crime and drugs) to inoculate against the potential class-based affinity.

DAMN this was a good one.

So another place I think you might poke around and find this myth: the debate between childfree people and people with children.

I was on Instagram (I know, that's a me problem) the other day and a creator I usually love posted a meme about how parents get to just go home early whenever because "kids" and the comment section was FROTHING. The usual stuff — parents doing the Rodney Dangerfield dance about how they get no respect (we don't!) or systemic support (also we don't!) and that American culture generally seems invested in making more babies and then screwing the people who need to raise them (also true!)

The child-free folks argued that it wasn't their job to pick up the slack because little Timmy has a tummy ache (fair!) and that having a kid is the only vaguely acceptable reason for needing to leave the office unexpectedly (also true!). But then it got mean.

"No one made you have a kid — that's your problem." — people mad at parents for having kids

I see this a lot (mostly with younger single folks) on the internet — the feeling that someone else having a child is an imposition on their comfort, and I think it has everything to do with the kind of frankensteining of Individualism and the Cult of Convenience that our phones and 2-day shipping has brought us. This vibe of "we have to share this planet but we don't have to like it — you clean up your own mess and I'll clean up mine." (I 100% used to be this person, and then I had a kid! Sorry to the moms and dads who I disregarded in my youth!)

There was a great On Being episode recently where Sarah Hendren talks about disability as this anti-american idea, like self-reliance is the most important personal value you can hold, even though every single one of us will at some point be dependent on someone else — even if just for a few days when we have the flu. She points out the ableist nature of this ideology, but also the incredible beauty of dependence. The humility it gives us. To know that we can't always take care of ourselves is a gift. Anyway, I loved this piece and I thought you might enjoy that thought thread for your book!

https://onbeing.org/programs/sara-hendren-our-bodies-aliveness-and-the-built-world/

I think about individualism all the time in terms of housing. I grew up driving past Co-Op City in the Bronx to the suburbs of Westchester and thinking snootily: "how can people live all squished up in those big ugly buildings?" Cheaply, sustainably, and in community for along time, is how! But I was taught not to want that, and I think we've wasted a lot of time idealizing living apart when we could have been figuring out how to live together.